Roman emperor Antonius Pius, Hadrian’s successor, had a lot to prove when he ascended the throne in the summer of 138 A.D. He had risen through the political ranks, not the military, and in fact as far as we know, Antonius never even got near a Roman legion. It was in Britain that he decided to prove his commander-in-chief chops by sending governor Quintus Lollius Urbicus north of Hadrian’s Wall into southern Scotland.

Roman emperor Antonius Pius, Hadrian’s successor, had a lot to prove when he ascended the throne in the summer of 138 A.D. He had risen through the political ranks, not the military, and in fact as far as we know, Antonius never even got near a Roman legion. It was in Britain that he decided to prove his commander-in-chief chops by sending governor Quintus Lollius Urbicus north of Hadrian’s Wall into southern Scotland.

Around 142 A.D. Antonius ordered that a wall be built marking the new northern border of Britannia. Urbicus deployed troops from the II Augusta, VI Victrix and XX Valeria Victrix legions to build the wall, starting with a foundation of stone topped with a turf rampart that was as high as 13 feet in places. The height of the wall was supplemented by a deep and wide ditch on the north side for added protection against the Caledonian hoards. It took 12 years to build and ended up stretching 39 miles across Scotland coast to coast from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde.

Around 142 A.D. Antonius ordered that a wall be built marking the new northern border of Britannia. Urbicus deployed troops from the II Augusta, VI Victrix and XX Valeria Victrix legions to build the wall, starting with a foundation of stone topped with a turf rampart that was as high as 13 feet in places. The height of the wall was supplemented by a deep and wide ditch on the north side for added protection against the Caledonian hoards. It took 12 years to build and ended up stretching 39 miles across Scotland coast to coast from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde.

For reasons not entirely clear to this day, the Romans abandoned the Antonine Wall just eight years after its completion in 162 A.D. Since the turf wall didn’t last as well as Hadrian’s stone one, what we have left in place today are the defense ditches, remains of the stone foundations of the wall and of the 20 plus forts and fortlets that guarded its length. Excavations have also unearthed a wealth of artifacts, including some that put Hadrian’s fancy pants wall to shame.

The University of Glasgow’s The Hunterian Museum in Glasgow has just opened a new permanent gallery dedicated to the sculptures and artifacts found over three centuries of research, excavation and study of the Antonine Wall.

Through The Hunterian’s rich collections the gallery investigates four key themes: The building of the Wall – its architecture and impact on the landscape; the role of the Roman army on the frontier – the life and lifestyle of its soldiers; the cultural interaction between Roman and indigenous peoples, and evidence for local resistance; and the abandonment of the Wall and the story of its rediscovery over the last 350 years.

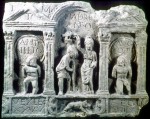

Among on the artifacts on display are 16 of the 19 surviving distance slabs, marble slabs elaborately carved by the legions to mark their work on the wall.

The sculptures are, in general, more elaborate and richly decorated than their counterparts on Hadrian’s wall, featuring such scenes as Victory placing a laurel wreath on a Roman legionary standard, and the distinctive mascots of the soldiers’ legions: a running boar for the XX; a Pegasus and a Capricorn (after the Emperor Augustus’s star sign) for the VI.

The sculptures also clearly project the move north as a splendid military victory: several depict Caledonians being trampled by Roman cavalry, or simply crouching in submission, bound and naked.

The gallery emphasizes that life along the wall was not the stark existence you might expect from the northernmost border of the Roman Empire. The remains of bathhouses have been found along the wall, and the number of valuable consumer goods like red Samianware dishes and glass found suggest that some people in the area lived very well indeed.