An archaeological excavation in the Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano, the square in front of the Archbasilica of St John Lateran in Rome, has uncovered complex layers of remains from different periods, including walls dating to between the 9th and 13th centuries A.D., the period in which the basilica and palace complex was known as the Patriarchate.

An archaeological excavation in the Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano, the square in front of the Archbasilica of St John Lateran in Rome, has uncovered complex layers of remains from different periods, including walls dating to between the 9th and 13th centuries A.D., the period in which the basilica and palace complex was known as the Patriarchate.

The Lateran archaeological area extends from just inside the Aurelian Walls near the ancient Porta Asinaria gate to the ground under the cathedral of St. John. The site is of crucial importance to the history of Rome and of Christianity. The sumptuous domus of the Laterani family was built there in the late Republic/early Empire. It was confiscated by Nero after Plautius Lateranus was executed for his role in the Pisonian conspiracy of 65 A.D.

The Lateran Palace had passed through the hands of imperial families and eventually inherited by Fausta, sister of the emperor Maximian. The former Domus Laterani thus became known as the Domus Faustae, and when Fausta was married to Constantine I in 306 A.D., the palace fell under his control. He is said to have given it to the Bishop of Rome around 313 A.D.

On the grounds of the domus a large cavalry barracks was built by Septimius Severus in 193 A.D. The Castra Nova Equitum Singularium was the fort of the Equites Singulares Augusti, the personal cavalry guard of the emperors. The regiment sided with the emperor Maxentius against Constantine at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 A.D., so after Constantine’s victory, he disbanded the Equites singulares Augusti and razed the Castra Nova.

On the grounds of the domus a large cavalry barracks was built by Septimius Severus in 193 A.D. The Castra Nova Equitum Singularium was the fort of the Equites Singulares Augusti, the personal cavalry guard of the emperors. The regiment sided with the emperor Maxentius against Constantine at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 A.D., so after Constantine’s victory, he disbanded the Equites singulares Augusti and razed the Castra Nova.

Constantine ordered construction of the first Christian basilica in Rome on the site of the demolished barracks. It was inaugurated in 324 A.D. It became the official seat of the Bishop of Rome, which it still is today, while the neighboring palace became the Pope’s official residence until the papacy was moved to Avignon in 1309.

The original basilica was all but destroyed in an earthquake in 896. The only visible remnant of the original church is the octagonal baptistery which dates to the 5th century. The church was rebuilt in phases. Much of what we see today is the work of baroque architect Borromini in the mid-17th century, and the statue-festooned façade was added in the 18th century.

Despite the great significance of the site, archaeological investigations have been few and far between and most of them precede modern methods. There have been no modern excavations of the square in front of the current basilica until now.

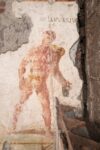

The finds attributable to the Patriarchate were found in the eastern part of the excavation, along its entire length: it is a structure that could have served both as a defensive wall for the papal residence and as a support for the slope that characterized the Lateran area in ancient times. In light of the different building techniques found, its construction can be dated to the 9th century AD and it was the subject of various restoration and reconstruction interventions until at least the 13th century.

The wall is made of large blocks of tuff, certainly reused from other structures that no longer exist. Evidence of one or more restoration interventions is the presence of a banding of the blocks on both sides, made with a facing of tuff blocks that have a series of buttresses. Continuing towards the West, the wall is instead made with wedge-shaped buttresses and a more irregular technique. The final part of the wall, which runs up to the parvis of the Basilica, has a facing of tuff blocks and buttresses this time of a square shape.

Defensive structures would have been very much needed in the period before the Avignon papacy (1309-1376). The noble families of Rome were constantly at war, with the Throne of Peter the main bone of contention, and the city was repeatedly sacked by, among others Arab raiders from Sicily (846) and Normans under Robert Guiscard (1084). The latter looted the city after being called to rescue Pope Gregory VII, holed up in Castel Sant’Angelo under siege by Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV. Guiscard did get Henry to retreat and delivered the pope safely to the Lateran, but Rome paid the price. The ancient city — Capitoline, Palatine, Colosseum — burned for days.

After the return of the popes to Rome, the Lateran was in such poor condition that they set up new digs in the Vatican. The defensive wall was buried and everyone forgot it had ever been there.

The archaeological investigations, although conducted in an emergency due to the timing dictated by the delivery of the works for the opening of the Jubilee year, have also brought to light the remains of other structures, dating back to periods preceding the Patriarchate.

At the centre of the excavation, a portion of a wall in opus reticulatum was identified, dating back to between the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD, whose function was to terrace the slope that characterised the area. More interesting are the imposing foundations in opus reticulatum dating back to the Severian period (3rd century), perhaps to be related to the Castra Nova equitum singularium , already documented under the current structure of the Basilica. Two walls in opus lateralis that run parallel are from the same period and, considering their depth (3.5 metres below the current floor level) and the short distance between them, they are probably part of an underground structure. Finally, in the central portion of the excavation, a section of a wall structure in opus listatum was found, dating back to between the 4th and 7th centuries.

All of the remains are being left where they were found. City authorities are studying how and when to continue the excavations (likely after the Jubilee) and what can be done to make them safe and accessible to visitors.