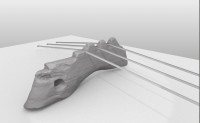

Archaeologists excavating the High Pasture Cave on the Isle of Skye have discovered a wooden fragment that they believe came from a lyre or similar stringed instrument. The fragment was burned and part of it broken off, but you can clearly see the carved string notches that identify it as a bridge. It was discovered in the rake-out deposits of the hearth outside the entrance to the cave. The deposits date to between 550 and 450 B.C., which would make the bridge a fragment of the oldest stringed instrument found in Europe.

Archaeologists excavating the High Pasture Cave on the Isle of Skye have discovered a wooden fragment that they believe came from a lyre or similar stringed instrument. The fragment was burned and part of it broken off, but you can clearly see the carved string notches that identify it as a bridge. It was discovered in the rake-out deposits of the hearth outside the entrance to the cave. The deposits date to between 550 and 450 B.C., which would make the bridge a fragment of the oldest stringed instrument found in Europe.

Artifacts and organic remains ranging from the Bronze to the Iron Age have been found in the High Pasture Cave. The large cave complex appears to have been put to a variety of uses over hundreds of years, including religious rituals. In 2006, archaeologists discovered a cache of antler and bone points dating to 500 B.C. in a section of the cave known as the Bone Passage. Seven of the pieces had an odd wear pattern at the tip suggesting they had been turned over and over again. Experts speculated at the time that they could have been used as tuning pegs for a lyre. Now they’ve found evidence of an actual lyre from the same period in the cave, so the speculation looks considerably more solid.

(Not that they’re a matched set or anything. They were found in different spots and reconstructions of the bridge suggest it came from a six-stringed instrument which would only need six tuning pegs.)

(Not that they’re a matched set or anything. They were found in different spots and reconstructions of the bridge suggest it came from a six-stringed instrument which would only need six tuning pegs.)

The oldest stringed instruments in the archaeological record have been found in what is now Iraq, like the bull-headed lyre found in the Royal Cemetery of Ur which dates to around 2500 B.C. Because stringed instruments are typically made out of wood, they usually rot before archaeologists can find them; in fact the sound box of the Ur lyre had rotted away, but the bitumen-covered front panel and the gold and lapis lazuli bearded bull’s head survived.

Musical instruments from Iron Age Europe were not the luxury models of ancient Sumer nor did they have the advantage of a dry, hot environment to preserve the wood. Even Roman-era instruments are so hard to come by that we have to rely on literature, mosaics and frescoes to learn about them, or carvings on altars like the one unearthed in Musselburgh in 2010 which until now was the earliest representation of a musical instrument ever found in Scotland. Finding a piece of an instrument that is centuries older than any previous discoveries and is so clearly recognizable as a piece of an instrument (the bridge is probably the single most recognizable part of a lyre because of its shape and the string notches) is therefore enormously significant to our understanding of ancient music and poetry in Europe.

Culture and External Affairs Secretary Fiona Hyslop added: “This is an incredible find and it clearly demonstrates how our ancestors were using music and ritual in their lives. The evidence shows that Skye was a gathering place over generations and that it obviously had an important role to play in the celebration and ritual of life more than 2,000 years ago.”

The artifact is being conserved by AOC Archaeology in Edinburgh. There are some nice views and models of the bridge in the following video, and a charming finale in which Dr. Graeme Lawson of Cambridge Music – Archaeological Research plays a reproduction ancient lyre.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFCvu0oKlvU&w=430]

Every day, I open up The History Blog to discover something new and interesting. The subjects covered are seemingly endless–and each one is fascinating–art, music, money, culture, discovery, etc. I couln’t imagine a more pleasant way to start the day than to open up this wonderful website, first thing in the morning.

I can think of one: seeing one of your kind, generous and encouraging comments first thing. :thanks:

Would you happen to know whether an actual archaeological report/paper was published describing the find in greater detail? I would appreciate a reference very much.

I don’t believe the find has been published yet. I read a number of news stories and press releases, none of which mentioned current or even upcoming publication. I think your best bet to find out is to contact Historic Scotland. It’s their press release that has been the primary source for all the media articles. Dr. Graeme Lawson seems very much in the know as well, but unfortunately his website is on the rudimentary side. It has no contact form functionality, nor does it list any contact information at all. That’s why I’d start with Historic Scotland.

Best of luck to you. 🙂

I make and play lyres for a living. I’m not entirely convinced by the bridge, but have real reservations about the pegs.

The bridge may well be a lyre bridge, but could also perhaps be something to do with weaving or carding. Assuming it is an instrument bridge then 6 strings is probably the right guess as nearly all ancient lyres from Europe (as opposed to Greek and Roman examples) have 6 strings. Tuned to the first 6 notes of a major scale they allow you to play a 3 chord trick and small compass melodies in both major and minor keys without retuning. There is no evidence for pentatonic tunings. Anyone interested might like to look at the Finnish Kantele tradition, a 5 stringed instrument not tuned pentatonically but with a whole repertoire of interesting music. It may well be that the absence of a seventh and a small compass of notes is a part of the style of ancient Northern European instrumental music.

I am really not convinced by the pegs. I would have expected a lyre of this antiquity to have the friction tuning levers that are laced to the yoke with rawhide, the way early Greek and Roman lyres were constructed, and the way that many Ethipian and Siberian lyres are still tuned today. Pegs/levers made for this style of tuning would be cylindrical with a polished and crushed mark in the centre where they rotated around the yoke.

I also can’t see any wear from a string or means of attaching a string to these ‘pegs’. I would have expected them to have notches in the end, or holes through them. The ends look quite intact and there is no sign of any notches or holes.

Also even if there are seven it does not mean that there would be seven strings. A peg might be a spare or even unused and just in place for symbolic or aesthetic reasons. There is a Welsh medieval poem where the poet requests a lyre (Crwth) be made with seven pegs, one of which is to be silent.

Just curious; what did these ancients use for strings on theit musical instruments?

I tend to agree with Corwen above.

The Romano – British pegs found in London do actually have a means of threading a string through the end of the peg, and there is also a triangulated head where the player can tune the string in the same manner as a piano tuner twists his string.

Crucially, unless we can receive answers to our enquiries from the keepers of these relics we are essentially just trying to peer at computer screens to ascertain whether such features are actually present, which inhibits our own academic efforts.