This is the last week of the British Museum’s exhibition of its impressive collection of etchings by Hercules Segers. Hercuwho, you might well ask, as did I when I first encountered him on the British Museum website. Short answer: Hercules Pieterszoon Segers (ca. 1589 – ca. 1638) was an incredibly innovative Dutch printmaker and painter during the Golden Age of Dutch art. He experimented with printing media in such radical ways that he was centuries ahead of his time. His imaginary landscapes of craggy mountains and desolate valleys printed on colored paper in colored ink look like something J.M.W. Turner might have painted two hundred years later, or rather, like texturized, color-washed, inverted negatives of something Turner might have painted two hundred years later.

This is the last week of the British Museum’s exhibition of its impressive collection of etchings by Hercules Segers. Hercuwho, you might well ask, as did I when I first encountered him on the British Museum website. Short answer: Hercules Pieterszoon Segers (ca. 1589 – ca. 1638) was an incredibly innovative Dutch printmaker and painter during the Golden Age of Dutch art. He experimented with printing media in such radical ways that he was centuries ahead of his time. His imaginary landscapes of craggy mountains and desolate valleys printed on colored paper in colored ink look like something J.M.W. Turner might have painted two hundred years later, or rather, like texturized, color-washed, inverted negatives of something Turner might have painted two hundred years later.

Segers’ prints still look incredibly fresh, possibly because they’ve been so seldom seen since his popularity ebbed shortly after his death around 1638. He was better known by his contemporaries for his paintings which were collected by Dutch masters Rembrandt van Rijn and Jan van de Cappelle. Rembrandt was a particular fan. Only a dozen of Segers’ paintings are known today, and Rembrandt owned eight of them.

Segers’ prints still look incredibly fresh, possibly because they’ve been so seldom seen since his popularity ebbed shortly after his death around 1638. He was better known by his contemporaries for his paintings which were collected by Dutch masters Rembrandt van Rijn and Jan van de Cappelle. Rembrandt was a particular fan. Only a dozen of Segers’ paintings are known today, and Rembrandt owned eight of them.

Rembrandt also collected Segers’ prints, which inspired his own far more famous etchings. One of Rembrandt’s etchings, in fact, was more than inspired by Segers’ work; it was built on it.  Rembrandt acquired one of Segers’ original copper plates, Tobias and the Angel, and reworked the figures into a Flight into Egypt. He made small changes to the landscape (mainly the copse of trees behind the Holy Family), but kept much of it the same, because the greatest of the Dutch Golden Age painters knew that there was no improving on the original.

Rembrandt acquired one of Segers’ original copper plates, Tobias and the Angel, and reworked the figures into a Flight into Egypt. He made small changes to the landscape (mainly the copse of trees behind the Holy Family), but kept much of it the same, because the greatest of the Dutch Golden Age painters knew that there was no improving on the original.

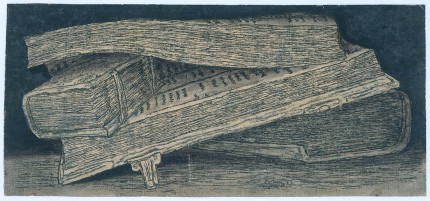

There are only 183 of Segers’ known prints extant, made from 54 original plates. Unlike Rembrandt, Dürer, Goya and every other printmaker you can name, Segers never made large print runs, and every single impression is different. Some of them are vastly different. He used colored ink printed on paper he dyed himself, sometimes running the paper and plate through the press with fabric to apply texture to the print. Sometimes he printed directly onto fabric.

There are only 183 of Segers’ known prints extant, made from 54 original plates. Unlike Rembrandt, Dürer, Goya and every other printmaker you can name, Segers never made large print runs, and every single impression is different. Some of them are vastly different. He used colored ink printed on paper he dyed himself, sometimes running the paper and plate through the press with fabric to apply texture to the print. Sometimes he printed directly onto fabric.  Once the print was pressed, he would hand-paint different details on each piece and often dipped the finished composition in a tint. Nobody else did this. He also experimented with different crops and cuttings, bringing a whole new focus to individual prints.

Once the print was pressed, he would hand-paint different details on each piece and often dipped the finished composition in a tint. Nobody else did this. He also experimented with different crops and cuttings, bringing a whole new focus to individual prints.

The results are so unprintlike that art historians have dubbed them “printed paintings,” and indeed his actual paintings are so small that they are about the same size as his large prints, so he blurred the demarcation line between print and paint in more ways than one.

He utilized existing printmaking techniques in new and startling ways, but he also broke entirely new ground. From the British Museum pdf about Segers:

His greatest invention was undoubtedly the process of lift-ground etching (also known as sugar-lift or sugar-bite etching, sugar aquatint or pen method). Although no accounts by Segers of his working methods have survived, it is assumed that he used a sugar solution to draw a composition on a copper-plate either with a pen or even with a brush, as some of the lines are quite broad. The plate was then probably covered with a thin, resinous ground and bathed in hot water which made the sugar granules swell causing the ground to blister off where the design had been applied. The plate would then have been treated as usual: the exposed copper-plate bitten in an acid bath, inked and subsequently printed. The resulting lines have a granulated surface, similar to aquatint which was a later invention. This technique, allowing the artist to apply defined lines with a brush, was not practiced again until the 18th century.

I checked my copy of H.W. Janson’s classic reference tome History of Art (mine is the Fifth Edition published in 1995) and Segers is not even mentioned in passing in the entire 1000 pages. Alexander Cozens, on the other hand, a fairly conventional British landscape watercolorist and printmaker who gets the credit for inventing aquatint over a century after Segers’ related invention, has six pages in the index.

I checked my copy of H.W. Janson’s classic reference tome History of Art (mine is the Fifth Edition published in 1995) and Segers is not even mentioned in passing in the entire 1000 pages. Alexander Cozens, on the other hand, a fairly conventional British landscape watercolorist and printmaker who gets the credit for inventing aquatint over a century after Segers’ related invention, has six pages in the index.

Segers’ genius began to get recognition again in the 19th century, when major purchases by the British Museum and the Rijksmuseum (click links for pictures of the museums’ Segers collections) put his work before a broader audience. Even so, the current exhibition at the British Museum is the first time all of their Segers etchings have been put on display as a group, and most of them have never been on display at all. If you’re in London, get thee to the BM stat.

Thank you for sharing Hercules Segers with those of us unable to visit the exhibition. What a wonder of prints this collection must be!

Your synopsis of Segers is as artfully crafted as the prints.

I am very interested in Segers’ innovative technique particularly in his printmaking on cloth both fine and course. I saw his prints on the British Museum’s website. the print on fine cloth was wonderful. The print on course cloth was not very clear. I am interested in the idea of stages. Can you help me get more information. Thank you

Im actually doing a research on Segers and the more I look into his work and learn about his life makes me admire him even more since we did not discuss him in class…So thank you so much!!

it also shows alot about Rembrandt’s approach to his prints.