British Museum conservators have been examining the hoard of coins found by archaeologists on Beau Street in Bath in November of 2007 and announced earlier this year. Although the painstaking process of excavating the coins from the solid block of soil, then cleaning and documenting them is still in the early stages, a number of unexpected discoveries have been made.

British Museum conservators have been examining the hoard of coins found by archaeologists on Beau Street in Bath in November of 2007 and announced earlier this year. Although the painstaking process of excavating the coins from the solid block of soil, then cleaning and documenting them is still in the early stages, a number of unexpected discoveries have been made.

The coins are fused together by a combination of soil and copper corrosion which makes the number hard to assess. Archaeologists first thought there were 1,000 coins in the hoard, but when they realized they were stuck together in stacks rather than more spread out, they revised the estimate putting the number of coins in the hoard at around 30,000. After some excavation, British Museum metals conservator Julia Tubman thinks the actual number is closer to 22,000, although some of her colleagues think there may be as many as 25,000 coins in the block.

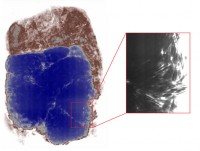

All of the coins were originally placed in either a stone-lined box which has since decayed or simply a stone-lined hole in the ground, but thanks to the dirt and corrosion, the coin block has still kept the shape of the cist in which they spent so many centuries. This is common in ancient hoards, but it turns out the coins of the Beau Street Hoard were not placed directly into the cist. X-rays of the soil block taken at University of Southampton’s Department of Engineering Sciences before conservation began reveal at least six distinct groupings of coins.

All of the coins were originally placed in either a stone-lined box which has since decayed or simply a stone-lined hole in the ground, but thanks to the dirt and corrosion, the coin block has still kept the shape of the cist in which they spent so many centuries. This is common in ancient hoards, but it turns out the coins of the Beau Street Hoard were not placed directly into the cist. X-rays of the soil block taken at University of Southampton’s Department of Engineering Sciences before conservation began reveal at least six distinct groupings of coins.

That means the entire hoard is actually composed of a half-dozen smaller hoards that were placed into the box, probably in bags. They could have been gathered at different times and placed in the box individually. Perhaps the cist was an official store, a lockbox in a temple, say, or kept by a banker or civic leader of some sort. They could have been buried together all at once, or they could have been sorted into bags just before burial.

Already the first coin samples taken from one side of the block during the Bath excavation have proven to be very different from coins removed from the block at the British Museum. The coins retrieved on site were small, debased, coppery coins from the late third century A.D. known as radiates. These are the most common type of coin found in hoards buried from 270 to 290 A.D.

The coins Julia Tubman has retrieved and cleaned at the lab are considerably older. She has been able to liberate two of the bags from the block (the two smallest at the top right of the x-ray) and one of the bags, bag five, contained silver denarii, mainly from the first half of the third century, suggesting that they were placed in the bag according to denomination rather than gradually accrued. These types of coins are characteristic of hoards buried in the 260s.

The coins Julia Tubman has retrieved and cleaned at the lab are considerably older. She has been able to liberate two of the bags from the block (the two smallest at the top right of the x-ray) and one of the bags, bag five, contained silver denarii, mainly from the first half of the third century, suggesting that they were placed in the bag according to denomination rather than gradually accrued. These types of coins are characteristic of hoards buried in the 260s.

Bag five also contains one of the major surprises of the hoard: a coin minted by Mark Antony in 32 B.C., just before the Battle of Actium. It’s so worn that it’s almost smooth, which means it was in circulation for hundreds of years before it was stashed in that bag. Another old coin dates to the very brief reign of Otho who was emperor from January 15th to April 16th of 69 A.D., the infamous Year of the Four Emperors.

Bag five also contains one of the major surprises of the hoard: a coin minted by Mark Antony in 32 B.C., just before the Battle of Actium. It’s so worn that it’s almost smooth, which means it was in circulation for hundreds of years before it was stashed in that bag. Another old coin dates to the very brief reign of Otho who was emperor from January 15th to April 16th of 69 A.D., the infamous Year of the Four Emperors.

Bag six coins haven’t been cleaned yet, but from the shape and size Tubman believes they are all late third century radiates.

Another big surprise is less impressive in a shiny sense, but perhaps even more remarkable from an archaeological perspective. It seemed unlikely at the beginning of the process that any remains of the bags would be discovered. They were made out of organic material of some kind, fabric or leather, and thus almost certain to have rotted into nothingness. Indeed, there are no pieces of material left per se, but there are remnants. Julia Tubman found flakes of light brown attached to the coins right at the borders of the bags. These areas are very clearly demarcated by the stacking patterns of the coin clusters. She has taken samples so the remains can be tested and confirmed as leather from the bags.

Another big surprise is less impressive in a shiny sense, but perhaps even more remarkable from an archaeological perspective. It seemed unlikely at the beginning of the process that any remains of the bags would be discovered. They were made out of organic material of some kind, fabric or leather, and thus almost certain to have rotted into nothingness. Indeed, there are no pieces of material left per se, but there are remnants. Julia Tubman found flakes of light brown attached to the coins right at the borders of the bags. These areas are very clearly demarcated by the stacking patterns of the coin clusters. She has taken samples so the remains can be tested and confirmed as leather from the bags.

The British Museum blog is posting regular entries about the Beau Street Hoard. Follow along as conservators reveal exciting new finds and for us nerdy few, exciting descriptions of the cautious and deliberate process of excavating this fascinating hoard.

Interesting story! Just one correction: Otho’s reign was in A.D. 69, not 69 B.C.

Why not move the Year of Four Emperors to the Roman Republic? It makes so much more sense that way. :no:

Correction made, thank you kindly. :thanks: