In a Romantic literature fan’s fantasy come true, Lord Byron’s personal copy of Frankenstein, inscribed to him by Mary Shelley, has been discovered in a private library and is going up for auction. It’s such an incredible confluence of iconic elements from the era, completely unique and so unlikely to have survived that it’s almost impossible to believe.

In a Romantic literature fan’s fantasy come true, Lord Byron’s personal copy of Frankenstein, inscribed to him by Mary Shelley, has been discovered in a private library and is going up for auction. It’s such an incredible confluence of iconic elements from the era, completely unique and so unlikely to have survived that it’s almost impossible to believe.

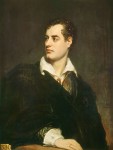

The story of how Frankenstein came to be would be legendary if it hadn’t actually happened. In May of 1816, poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, his lover and future wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and her stepsister Claire Claremont rented a small house on Lake Geneva next to the Villa Diodati, the stately home where poet and rakehell Lord Byron was staying with his personal physician John William Polidori. They planned to spend the summer together enjoying the natural beauty of the area, but they were thwarted by a volcano.

The eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in April of 1815 was the world’s largest since 180 A.D., and it drove so much ash into the air that famine, floods, massive rainfalls and other bizarre weather phenomena wreaked havoc all over the world the next year. Thus 1816 became known as “the year without a summer,” and our friends in Switzerland found their plans for lovely picnics, lakeside walks and boat rides ruined by the constant rain and unseasonably cold temperatures.

The eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in April of 1815 was the world’s largest since 180 A.D., and it drove so much ash into the air that famine, floods, massive rainfalls and other bizarre weather phenomena wreaked havoc all over the world the next year. Thus 1816 became known as “the year without a summer,” and our friends in Switzerland found their plans for lovely picnics, lakeside walks and boat rides ruined by the constant rain and unseasonably cold temperatures.

To pass the time, the company read each other ghost stories. According to Mary Shelley’s introduction to the third edition of Frankenstein, the first illustrated edition and the first one in which authorship was attributed to her rather than kept anonymous, Byron proposed that each of them write a ghost story of their own. All accepted the challenge. Percy Shelley wrote Fragment of a Ghost Story, Polidori wrote a story about a woman whose head is turned into a skull after she looks through a keyhole at something she had been prohibited from viewing, and Byron wrote the beginning of a vampire story which Polidori would later use as a jumping off point for his novel The Vampyre, initially erroneously published under Byron’s name. This was the first modern vampire novel, the foundation of the rich, ruthless, attractive blood-sucking immortal that still stalks our nights.

Mary, daunted by her own ambition to create a story that would be truly scary and rival the ones they had already read, couldn’t seem to muster up a good idea. One night, after listening to Byron and Shelley discuss Erasmus Darwin, galvanism and the reanimation of dead flesh, that good idea finally came to her.

Mary, daunted by her own ambition to create a story that would be truly scary and rival the ones they had already read, couldn’t seem to muster up a good idea. One night, after listening to Byron and Shelley discuss Erasmus Darwin, galvanism and the reanimation of dead flesh, that good idea finally came to her.

My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness far beyond the usual bounds of reverie. I saw — with shut eyes, but acute mental vision, — I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handywork, horror-stricken. He would hope that, left to itself, the slight spark of life which he had communicated would fade; that this thing, which had received such imperfect animation, would subside into dead matter; and he might sleep in the belief that the silence of the grave would quench for ever the transient existence of the hideous corpse which he had looked upon as the cradle of life. He sleeps; but he is awakened; he opens his eyes; behold the horrid thing stands at his bedside, opening his curtains, and looking on him with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes.

I opened mine in terror. The idea so possessed my mind, that a thrill of fear ran through me, and I wished to exchange the ghastly image of my fancy for the realities around. I see them still; the very room, the dark parquet, the closed shutters, with the moonlight struggling through, and the sense I had that the glassy lake and white high Alps were beyond. I could not so easily get rid of my hideous phantom; still it haunted me. I must try to think of something else. I recurred to my ghost story, my tiresome unlucky ghost story! O! if I could only contrive one which would frighten my reader as I myself had been frightened that night!

Swift as light and as cheering was the idea that broke in upon me. “I have found it! What terrified me will terrify others; and I need only describe the spectre which had haunted my midnight pillow.” On the morrow I announced that I had thought of a story. I began that day with the words, It was on a dreary night of November, making only a transcript of the grim terrors of my waking dream.

The short story that resulted was so successful that Shelley encouraged her to expand it into a novel. When they returned to England in September, Mary was incubating a great classic of literature and Claire the illegitimate daughter of Lord Byron to whom she would give birth in January of 1817. Mary finished writing Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus in the summer and published a small first edition of 500 in January of 1818. The publishers gave her six presentation copies to give away; one of them she put aside to give to Byron, the man who had started it all.

After the birth of Alba, Claire had written incessantly to Byron, begging him to take them both in, reminding him of their passionate lovemaking and threatening suicide when he rejected her. These letters only alienated him further, and Byron had never exactly been smitten with her. The month his daughter was born he wrote this to a friend:

After the birth of Alba, Claire had written incessantly to Byron, begging him to take them both in, reminding him of their passionate lovemaking and threatening suicide when he rejected her. These letters only alienated him further, and Byron had never exactly been smitten with her. The month his daughter was born he wrote this to a friend:

You know–& I believe saw once that odd-headed girl—who introduced herself to me shortly before I left England—but you do not know—that I found her with Shelley and her sister at Geneva—I never loved her nor pretended to love her—but a man is a man–& if a girl of eighteen comes prancing to you at all hours of the night—there is but one way—the suite of all this is that she was with child–& returned to England to assist in peopling that desolate island…This comes of “putting it about” (as Jackson calls it) & be dammed to it—and thus people come into the world.

Yeah, Byron was not a nice guy when it came to women. The end-result of their ugly correspondence was that Bryon refused to have anything to do with his daughter unless she was sent to him without her mother. He would acknowledge her and take financial responsibility for her, but only on condition that Claire be nowhere near. He also demanded that her name be changed to Allegra, which it was.

Yeah, Byron was not a nice guy when it came to women. The end-result of their ugly correspondence was that Bryon refused to have anything to do with his daughter unless she was sent to him without her mother. He would acknowledge her and take financial responsibility for her, but only on condition that Claire be nowhere near. He also demanded that her name be changed to Allegra, which it was.

In March, the Shelleys (now married after the horrible suicide of his first wife Harriet had made him a widower), Claire Claremont and Allegra left England for Italy. Claire felt that her daughter’s wealthy, titled father could provide advantages that she could not, so she agreed to Byron’s heartless condition. Shelley had some hope that he might be made to see reason. Their plan was to meet up with Byron, who was staying in Venice at the time, and work something out. In letter after letter Percy Shelley tried to persuade Byron that this forced separation would be unconscionably cruel to Claire and to the child, but he was unmovable. He would not accept their parent-trap invitation to go to their villa in Lake Como to pick up Allegra, nor would he allow Claire to accompany Allegra to Venice.

In the midst of this extra-legal custody battle (you can read some of it here; poor Shelley was stuck in the middle in the worst way), Mary Shelley’s hopes that she’d be able to give Byron his inscribed copy of Frankenstein in person faded. In the end Shelley shipped the three-volume first edition to Byron in a parcel along with some other books.

You will receive your packets of books. [Leigh] Hunt sends you one he has lately published; and I am commissioned by an old friend of yours to convey “Frankenstein” to you, and to request that if you conjecture the name of the author, that you will regard it as a secret. In fact, it is Mrs. S'[helley]s. It has met with considerable success in England ; but she bids me say, “That she would regard your approbation as a more flattering testimony of its merit.”

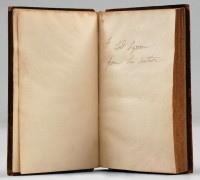

She signed it without signing it, writing “To Lord Byron from the author” in keeping with her desire for authorial anonymity.

She signed it without signing it, writing “To Lord Byron from the author” in keeping with her desire for authorial anonymity.

Byron’s reply to Shelley, if there was one, has not survived, but his opinion of Frankenstein has. In May of 1819 Byron wrote to his publisher John Murray:

Mary Godwin (now Mrs. Shelley) wrote “Frankenstein”—which you have reviewed thinking it Shelley’s—methinks it is a wonderful work for a Girl of nineteen—not nineteen indeed—at that time

(That whole letter covers so many juicy details it’s amazing. He talks about receiving a proof of his epic poem Don Juan, crushes his old friend Hobhouse’s charge against it of “indelicacy,” denies that he wrote The Vampyre, confirms Polidori’s claim in the introduction that Shelley freaked out one night while they were telling ghost stories although he can’t confirm that it’s because he hallucinated that the women had eyes on their breasts, rebuts in strenuous terms Poet Laureate Robert Southey’s lurid accusations of an incestuous threesome between Byron, Mary and Claire, plus describes a stormy night in which Shelley, who could not swim, kept his calm when the boat seemed about to capsize and refused Byron’s offer to save him should the worst happen. In June of 1822, three years after that letter was written, Shelley drowned when his boat capsized in a storm off the coast of Liguria. Little Allegra, just five years old, died two months before him.)

After Byron’s death in 1824, his library was dispersed by John Murray whom Byron had appointed the executor of his estate. In January, 1825, Murray received five boxes of Byron’s books shipped to him from Greece, where Byron had died of fever while fighting for Greek independence. He gave many of them away to Byron’s friends, then held a public sale in July to sell the rest. We know the titles offered at that sale. This one was not listed among them.

After Byron’s death in 1824, his library was dispersed by John Murray whom Byron had appointed the executor of his estate. In January, 1825, Murray received five boxes of Byron’s books shipped to him from Greece, where Byron had died of fever while fighting for Greek independence. He gave many of them away to Byron’s friends, then held a public sale in July to sell the rest. We know the titles offered at that sale. This one was not listed among them.

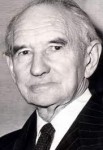

Perhaps Murray kept it. He could have given it away or he could have sold it privately. All we know for sure is that one volume of the three survived, the first volume with the remarkable anonymous inscription of its author, winding up in the library of Labour Member of Parliament Douglas Jay, Baron Jay. That’s where it was found almost two centuries later by his grandson when he was going through some of Lord Jay’s papers in 2011. Jay was a good friend of Jock Murray, direct descendant of John Murray, so it’s possible he received the book via his Murray connection. He was also an avid Byron collector, so he could have gotten the book through other contacts as well.

Perhaps Murray kept it. He could have given it away or he could have sold it privately. All we know for sure is that one volume of the three survived, the first volume with the remarkable anonymous inscription of its author, winding up in the library of Labour Member of Parliament Douglas Jay, Baron Jay. That’s where it was found almost two centuries later by his grandson when he was going through some of Lord Jay’s papers in 2011. Jay was a good friend of Jock Murray, direct descendant of John Murray, so it’s possible he received the book via his Murray connection. He was also an avid Byron collector, so he could have gotten the book through other contacts as well.

There is only one other surviving copy of Frankenstein inscribed by Mary Shelley. It’s an extremely important first edition from a literary perspective because it includes marginal notes, cross-outs and changes in her own hand that would be made to later editions. Mary gave this copy to an English friend of hers known only as Mrs. Thomas out of gratitude for her kindness to her after she was devastated by Shelley’s death in 1822. This copy is now in the Morgan Library in New York City.

As significant and touching as that version is, the Byron version may even top it. His connection to the foundation of the Frankenstein mythos, the references to it in some of Shelley’s and Byron’s most drama-crammed letters, puts the modest volume square in the center of the vortex of relationships that defined the Romantic era.

Lord Byron’s copy of Frankenstein will be on display at rare bookseller Peter Harrington Books from September 26th to October 3rd. They are taking offers of no less than £350,000 (about $568,000), but of course the sky’s the limit on something this special. Let us all cross our fingers and toes that it ends up in a public institution like the Bodleian Library at Oxford which has a great many of Mary Shelley’s papers, including the original notebooks in which she wrote the first draft of Frankenstein with Percy Shelley’s edits.

Lord Byron’s copy of Frankenstein will be on display at rare bookseller Peter Harrington Books from September 26th to October 3rd. They are taking offers of no less than £350,000 (about $568,000), but of course the sky’s the limit on something this special. Let us all cross our fingers and toes that it ends up in a public institution like the Bodleian Library at Oxford which has a great many of Mary Shelley’s papers, including the original notebooks in which she wrote the first draft of Frankenstein with Percy Shelley’s edits.

The Bodleian Library has an excellent online exhibition of some of the highlights of its Shelley collection, including both of Mary’s Frankenstein notebooks that you can read page by page in a zoomable viewer. Here’s volume one, and here’s volume two.

While we’re discussing Frankenstein monsters and Vampyres, who here remembers the first literary appearance of mummy. (Or Jane Webb Loudon?) Whole lot of creepy going on at that time, it seems.

I thought The Mummy was the scariest of all monsters when I was a kid. Gotta love the explosion of Gothic horror in the early 19th century. So much greatness poured forth.

I think this is cool how many artifacts and digs that are going on right now. Who was it that try to take credit for Frankenstein because Mary Shelley was a woman?

I’m not sure. I know many people refused to believe it could have been Mary’s work and attributed it to Percy, but he never took the credit himself.

Mad, bad and dangerous to know, indeed.

He actually compared Claire to Lady Caroline Lamb, who famously coined that apt phrase the night she met Byron. He put them both in the crazy bitches category where he could easily write them off no matter how fair their objections.

Well thankfully, women today don’t have to put up with such shenanigans.

One of those very rare instances where its being an incomplete set and its condition won’t hurt or destroy the value.

True that. All the value in this case is in volume one.

A fascinating story and a wonderful post.

Truly a great blog here about history

BENJAMIN MARCUS RAUCHER

Thank you, Benjamin. 🙂

Clare Clairmont didn’t put up with it. She never married, made her own living her own way, and villified Byron to the end of her days for letting their daughter die.