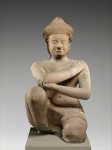

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has agreed to return two 10th-century Khmer statues looted from Cambodia during the chaos of the early 1970s. The matching sandstone statues, known as the Kneeling Attendants, were donated to the museum in four pieces during the 80s and 90s. According to a statement released by the Met, museum officials were recently presented with new research proving that these statues were looted from the Koh Ker archaeological site 80 miles northeast of Angkor Wat some time after 1970.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has agreed to return two 10th-century Khmer statues looted from Cambodia during the chaos of the early 1970s. The matching sandstone statues, known as the Kneeling Attendants, were donated to the museum in four pieces during the 80s and 90s. According to a statement released by the Met, museum officials were recently presented with new research proving that these statues were looted from the Koh Ker archaeological site 80 miles northeast of Angkor Wat some time after 1970.

The Met has refused to specify what this new evidence is, but the bases of the statues with the feet still on them that looters left behind were discovered in 2007 and witness statements from surrounding villagers establish that the statues were virtually untouched as recently as 1970. As usual, both Cambodia and the Met are going through the motions of pretending the museum did nothing wrong when they accepted these artifacts without an ownership history even though anybody can tell just from the pictures that the statues were crowbarred or chiseled off their pedestals. The knees bear clear marks of their brutal removal.

The Met has refused to specify what this new evidence is, but the bases of the statues with the feet still on them that looters left behind were discovered in 2007 and witness statements from surrounding villagers establish that the statues were virtually untouched as recently as 1970. As usual, both Cambodia and the Met are going through the motions of pretending the museum did nothing wrong when they accepted these artifacts without an ownership history even though anybody can tell just from the pictures that the statues were crowbarred or chiseled off their pedestals. The knees bear clear marks of their brutal removal.

The acquisition itself was in theory a donation. According to the Met’s website, the head of this figure was donated in 1987 and the body in 1992, both by collector Douglas Latchford. The head of the second figure was donated by Raymond G. and Milla Louise Handley in 1989, the body by Douglas Latchford in the same 1992 gift. Conservators reattached the heads to the bodies and in 1994 put the Attendants on either side of the doorway to the museum’s South and Southeast Asian Art gallery.

Martin Lerner, the Met’s Southeast Asian Art curator from 1972 to 2004 and the person in whose honor Latchford donated the pieces, noted in the 1994 recent acquisitions issue of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin:

“The most significant gift to the South and Southeast Asia collections in 1992 was undoubtedly a rare pair of large Cambodian kneeling male figures dating to the first half of the tenth century … It is particularly gratifying that the monumental bodies join up with heads already in the collection.”

My, what a gratifying coincidence. It’s almost as if somebody deliberately broke the statues to sell them piecemeal so they could be put back together a few years later while still granting the buyers plausible deniability. Spoiler: somebody deliberately broke the statues to sell them piecemeal so they could be put back together a few years later while still granting the buyers plausible deniability. This is a common practice in the penumbra where the antiquities underworld and reputable intstitutions/collectors meet. It could have been the looters who crowbarred the statues off their bases at the Prasat Chen temple in Koh Ker, or it could have been the middlemen who sold all four of the pieces to Spink & Son, London dealers who specialize in Asian art.

My, what a gratifying coincidence. It’s almost as if somebody deliberately broke the statues to sell them piecemeal so they could be put back together a few years later while still granting the buyers plausible deniability. Spoiler: somebody deliberately broke the statues to sell them piecemeal so they could be put back together a few years later while still granting the buyers plausible deniability. This is a common practice in the penumbra where the antiquities underworld and reputable intstitutions/collectors meet. It could have been the looters who crowbarred the statues off their bases at the Prasat Chen temple in Koh Ker, or it could have been the middlemen who sold all four of the pieces to Spink & Son, London dealers who specialize in Asian art.

Mr. Latchford has a different story about how these statues made their way to the Met. According to this New York Times article, he never actually owned the statues; he was just a conduit for the Met’s wishes.

“Spinks had had the pieces for some time,” Mr. Latchford said, “and they had not sold, so in honor of the curator, who was Martin Lerner, they requested that I would provide financial aid to donate them, and that’s what I did and why they are in my name.”

Mr. Latchford said that he did not know where Spink had gotten the items, that he never took possession of them, and that he does not have any documents from the transaction. He recalled spending about £10,000. A spokesman for Spink said it no longer has any of the paperwork from that era.

So if he bought all three of them at the same time at the museum’s request, then the Met’s acquisition information is false. The article also placed the Handley donation in 1987, while the Met says it was in 1989, two years after the first Latchford donation. Meanwhile, Spink is selling heads alone over the course of years even though it has the bodies in stock. I’m calling it right now: shady. Shady Sadie serving lady.

The Met is wise to unload their questionably-acquired pieces now before the law gets involved. I can’t help but wonder if that consideration underpins the decision even more than this mysterious “new research.” Sotheby’s is in the cross-hairs of the US Attorney right now over a statue looted from the same temple in Koh Ker.

Koh Ker was briefly the capital of the Khmer empire (928–944 AD) and the explosion of building in the city produced a wealth of exceptional carving, including the two Kneeling Attendants, Duryodhana, a 500-pound sandstone sculpture of a warrior that once stood in front of the western pavilion of Prasat Chen, and a matching statue of his arch-enemy Bhima, who stood across from him posed in perpetual conflict. These four were part of a group of 12 statues that have all been looted from the temple since the late 60s/early 70s. Bhima is now in the permanent collection of the Norton Simon Art Foundation in Pasadena (listen to the child’s audio tour on the website to hear some serious irony), although perhaps not for long since the Cambodian government has asked the US to help them recover Bihma, just as they have asked the US to help them recover Duryodhana from Sotheby’s.

Koh Ker was briefly the capital of the Khmer empire (928–944 AD) and the explosion of building in the city produced a wealth of exceptional carving, including the two Kneeling Attendants, Duryodhana, a 500-pound sandstone sculpture of a warrior that once stood in front of the western pavilion of Prasat Chen, and a matching statue of his arch-enemy Bhima, who stood across from him posed in perpetual conflict. These four were part of a group of 12 statues that have all been looted from the temple since the late 60s/early 70s. Bhima is now in the permanent collection of the Norton Simon Art Foundation in Pasadena (listen to the child’s audio tour on the website to hear some serious irony), although perhaps not for long since the Cambodian government has asked the US to help them recover Bihma, just as they have asked the US to help them recover Duryodhana from Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s has been trying to sell Duryodhana, which appropriately means “difficult to fight with,” for its Belgian owner since 2011, but two auction attempts have been blocked. The first was in March 2011 when Cambodia sent a letter claiming the statue had been illegally removed and requesting it be withdrawn from sale. The second was in April 2012 when U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Preet Bharara filed a civil suit in federal court seeking forfeiture of the statue on Cambodia’s behalf on the grounds that it was looted and exported in contravention of cultural patrimony laws from 1953 and that Sotheby’s knew all along it was stolen.

Sotheby’s has been trying to sell Duryodhana, which appropriately means “difficult to fight with,” for its Belgian owner since 2011, but two auction attempts have been blocked. The first was in March 2011 when Cambodia sent a letter claiming the statue had been illegally removed and requesting it be withdrawn from sale. The second was in April 2012 when U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Preet Bharara filed a civil suit in federal court seeking forfeiture of the statue on Cambodia’s behalf on the grounds that it was looted and exported in contravention of cultural patrimony laws from 1953 and that Sotheby’s knew all along it was stolen.

Sotheby’s denies everything, of course. They say they have no evidence the statue was stolen and that anyway the 1953 French colonial laws are ambiguous, and there’s no clearly stated cultural patrimony law that gives the current nation of Cambodia “ownership of everything a long-defunct regime made and then abandoned 50 generations ago.” So apparently anyone can just walk in and out of Cambodia with armfuls of Khmer artifacts because they were “abandoned.” Another shamelessly disingenuous argument Sotheby’s had made in retort is that they “have never seen nor been presented with any evidence that specifies when the sculpture left Cambodia over the last 1,000 years,” like the world has been swimming in 500-pound Cambodian statues since the turn of the first millennium but for some inexplicable reason this one just hasn’t appeared anywhere on the market, in museums or in collections until 975 years later. Absurd and offensive, not to mention that it contradicts their ludicrous abandonment argument since if they were looted and shipped out of country up to a thousand years ago, obviously they were not abandoned for 50 generations.

Sotheby’s denies everything, of course. They say they have no evidence the statue was stolen and that anyway the 1953 French colonial laws are ambiguous, and there’s no clearly stated cultural patrimony law that gives the current nation of Cambodia “ownership of everything a long-defunct regime made and then abandoned 50 generations ago.” So apparently anyone can just walk in and out of Cambodia with armfuls of Khmer artifacts because they were “abandoned.” Another shamelessly disingenuous argument Sotheby’s had made in retort is that they “have never seen nor been presented with any evidence that specifies when the sculpture left Cambodia over the last 1,000 years,” like the world has been swimming in 500-pound Cambodian statues since the turn of the first millennium but for some inexplicable reason this one just hasn’t appeared anywhere on the market, in museums or in collections until 975 years later. Absurd and offensive, not to mention that it contradicts their ludicrous abandonment argument since if they were looted and shipped out of country up to a thousand years ago, obviously they were not abandoned for 50 generations.

The government has archaeological research pointing to the statue’s being in country until the early 1970s, and even juicier, they have an email trail showing Sotheby’s conspiring to obscure the truth of its provenance. In emails between Emma C. Bunker, a scholar of Khmer art hired by the auction house to write the catalog entry, and a Sotheby’s official, Bunker straight up tells them it was stolen.

The complaint [starting on page 11] quoted a e-mail from the scholar warning an unnamed Sotheby’s official about attempting to sell the statue at auction: “The Cambodians in Phnom Penh now have clear evidence that it was definitely stolen from Prasat Chen at Koh Ker, as the feet are still in situ.”

Ms. Bunker said in an interview that she had urged Sotheby’s not to sell the statue at public auction but rather privately, to attract less attention. But, she said, she did so only after Sotheby’s officials assured her they had clear provenance on the statue. “They swore — swore — to me they had proper information,” she said. “They didn’t have the all-clear.”

They did have a sworn statement submitted to United States Customs and Border Protection by the owner stating that “to the best of my knowledge” the statue “is not cultural property documented as appertaining to the inventory of a museum or religious or secular monument or similar institution in Cambodia,” but given that Bunker told Sotheby’s exactly where it came from, that “to the best of my knowledge” is just a pathetic cover to keep the owner out of legal trouble.

A recent ruling allowed the auction house to keep the statue while the case is winding its way through the system, but all attempts to dismiss the lawsuit have thus far failed. Sotheby’s says the Met’s decision to return their looted Koh Ker statues has no bearing on their case, and maybe it doesn’t from a legal standpoint. It may be an indicator of the way the wind is blowing, though.

The same is true for the museum collections of Buddha heads. How can any curator accept these heads when one can clearly see the marks of chainsaws and chisel gouges.

Begone thief!

Love how the Met’s provenance on these over 1000 year old statues goes back to 1987. Also, all the Related Content statues in their image gallery have their feet chopped off as well. They are all in beautiful condition otherwise. It looks obvious that someone came along and suddenly broke them away.

I would think a conservator could tell just how recently the hacking-off occurred- no wear occuring after the damage, marks made by modern tools, etc. Shame on the Met. Shame on Sotheby’s.