Archaeologists excavating the site of the Neptune Shipyard in Newcastle upon Tyne, northeastern England, before development have discovered a 25-meter (82 feet) stretch of an 18th century wooden railway. These rails weren’t transporting trains — they wouldn’t be invented until the next century — but rather wooden wagons, aka chaldrons, pulled by horses. This is a section of the Willington Waggonway built in the 1760s to transport coal from several local collieries to the river Tyne.

Archaeologists excavating the site of the Neptune Shipyard in Newcastle upon Tyne, northeastern England, before development have discovered a 25-meter (82 feet) stretch of an 18th century wooden railway. These rails weren’t transporting trains — they wouldn’t be invented until the next century — but rather wooden wagons, aka chaldrons, pulled by horses. This is a section of the Willington Waggonway built in the 1760s to transport coal from several local collieries to the river Tyne.

Coal mining defined Newcastle starting in the Middle Ages (the expression “carrying coal to Newcastle” meaning a pointless activity dates to the 1600s) and the networks of waggonways were essential to the development of the industry. They enabled collieries to transport far more coal than wagons on traditional roads. One horse could deliver between 10 to 13 long tons of coal per trip along the waggonways, four times more than that same horse could deliver off track. They were built like Roman aqueducts, at a slight downhill incline from colliery to dock, whenever possible so gravity could help drive the wagons.

Coal mining defined Newcastle starting in the Middle Ages (the expression “carrying coal to Newcastle” meaning a pointless activity dates to the 1600s) and the networks of waggonways were essential to the development of the industry. They enabled collieries to transport far more coal than wagons on traditional roads. One horse could deliver between 10 to 13 long tons of coal per trip along the waggonways, four times more than that same horse could deliver off track. They were built like Roman aqueducts, at a slight downhill incline from colliery to dock, whenever possible so gravity could help drive the wagons.

The archaeologists were expecting to find Roman remains because the fort of Segedunum, the easternmost fort on Hadrian’s Wall, is less than five miles away, but they were far from disappointed with what they found instead. It’s a discovery of major historical significance, not just because of its importance to the history of the region, but because the rail gauge is standard gauge, still the most widely used rail width in the world. This is the earliest example of it known to survive and it’s exceptionally well preserved, thanks yet again to a waterlogged environment.

The archaeologists were expecting to find Roman remains because the fort of Segedunum, the easternmost fort on Hadrian’s Wall, is less than five miles away, but they were far from disappointed with what they found instead. It’s a discovery of major historical significance, not just because of its importance to the history of the region, but because the rail gauge is standard gauge, still the most widely used rail width in the world. This is the earliest example of it known to survive and it’s exceptionally well preserved, thanks yet again to a waterlogged environment.

Historians can now see something in three dimensions that they’ve only been able to study in books, drawings and paintings.

Archaeologists have revealed a “main way” heavy duty waggonway lined with double wooden rails, one laid on top of the other to prolong the life of the system. A loop from the main line enters a dip which would once have been a pond into which the wooden wheels of the coal wagons would have been immersed to stop them from drying out and cracking. […]

The pond loop has a stone central section between the rails which the horse drawing the waggon would have used to stay dry.

It’s no coincidence that the steam locomotives which replaced the wagon transport came to share Willington Waggonway’s gauge. The collieries along the Tyne used a variety of gauges ranging from as small as 3’10” to as wide as 5’0″. George Stephenson, later known as the “Father of the Railways,” worked for the collieries from a very young age, starting out as a picker cleaning coal of stones and other debris, then rose through the ranks. By the age of 15 he was a fireman. By the age of 17, he was an engineer of a stationary fire engine. The next year he went to night school where he learned to read for the first time. In 1802, when he was 21 years old, he worked as a brakesman at a coal pit in Willington Quay.

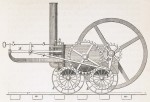

That same year, Cornishman Richard Trevithick designed the first steam engine tramway locomotive. That design came to fruition two years later, hauling 10 tons of iron on February 22, 1804, for the iron works at Penydarren in Wales. It only made three trips before the seven-ton engine broke the cast iron rails, so the iron works abandoned it as impractical. Trevithick built his second locomotive in 1805 for the Wylam Colliery in Tyneside. This was one weighed a mere 4.5 tons but it was using 5′ wooden tracks built for the wagons in 1748. Again, the tracks could not handle Trevithick’s engine.

That same year, Cornishman Richard Trevithick designed the first steam engine tramway locomotive. That design came to fruition two years later, hauling 10 tons of iron on February 22, 1804, for the iron works at Penydarren in Wales. It only made three trips before the seven-ton engine broke the cast iron rails, so the iron works abandoned it as impractical. Trevithick built his second locomotive in 1805 for the Wylam Colliery in Tyneside. This was one weighed a mere 4.5 tons but it was using 5′ wooden tracks built for the wagons in 1748. Again, the tracks could not handle Trevithick’s engine.

George Stephenson watched the trials and was impressed despite the ultimate failure of the locomotive. His early experience with fire engines and hard-won education developed into an engineering career. By 1813, he was the engine-wright at the Killington Colliery, improving many of their mining machines and in charge of all steam engines. In 1814, Stephenson built his first locomotive for the Killingworth Waggonway which had been joined to the Willington line in 1801. He used the gauge that he was most familiar with from his years of work on the line: Willington Waggonway’s 4’8″ gauge.

Stephenson’s locomotive worked. On its first trip it drew eight loaded wagons weighing 30 tons at four miles per hour. Thereafter it went into regular operation on the Killingworth Waggonway. (Fun fact: that first locomotive was named Blücher after Prussian general Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Anybody who has seen Young Frankenstein knows how to respond.) He spent the next years building railways, locomotives and stationary steam engines for many of the area collieries. Some of those locomotives remained in use for decades.

Stephenson’s locomotive worked. On its first trip it drew eight loaded wagons weighing 30 tons at four miles per hour. Thereafter it went into regular operation on the Killingworth Waggonway. (Fun fact: that first locomotive was named Blücher after Prussian general Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Anybody who has seen Young Frankenstein knows how to respond.) He spent the next years building railways, locomotives and stationary steam engines for many of the area collieries. Some of those locomotives remained in use for decades.

In 1823, Stephenson was appointed Chief Engineer of the Stockton & Darlington Railway. He designed the whole thing from top to bottom — selecting the locations, building the tracks, structures, trains, everything. Again he used the 4’8″ gauge that he knew best. On September 27th, 1825, the first railway built to carry the general public rather than an industrial product opened. He then moved on to build the Liverpool & Manchester railway, the first inter-urban passenger railway with timetables and tickets for passenger travel. It also carried raw and finished materials between the port of Liverpool and the textile mills of Manchester. The first run was on September 15th, 1830, and you guessed it, it was on 4’8″ gauge tracks.

In 1823, Stephenson was appointed Chief Engineer of the Stockton & Darlington Railway. He designed the whole thing from top to bottom — selecting the locations, building the tracks, structures, trains, everything. Again he used the 4’8″ gauge that he knew best. On September 27th, 1825, the first railway built to carry the general public rather than an industrial product opened. He then moved on to build the Liverpool & Manchester railway, the first inter-urban passenger railway with timetables and tickets for passenger travel. It also carried raw and finished materials between the port of Liverpool and the textile mills of Manchester. The first run was on September 15th, 1830, and you guessed it, it was on 4’8″ gauge tracks.

At some point in the 1830s an extra half-inch was added to the Liverpool & Manchester tracks to give the flanges a little extra space for lateral movement during higher speed runs and to reduce binding between the train’s wheels and the track on curves. Because Liverpool’s port was such an important hub for industrial transportation, L&M’s tracks became the British standard when it was established by the Railway Regulation Act of 1846. Because of Britain’s global empire and economic power, other countries employed the same standard.

A ver4y interesting article in many ways. I’m struck by how the standard gauge came to about – biologists are forever talking about how anatomical features on beasties are there because the cat/beaver/whatever is so perfectly adapted to its environment: but the standard gauge came about by pure chance.

Chance plays an important role in biological evolution too, via random mutations that prove advantageous to survival and reproduction. But yeah, no question standard gauge was born of coincidence. Later in his life, Stephenson admitted that if he could do it all again, he’d add a few inches to the gauge because he felt 4’8.5″ was just a tad too restrictive.