The Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, is the proud owner of a little-known and seldom-seen collection of illustrations for Edgar Allen Poe’s 1845 masterpiece The Raven drawn by artist James Carling in 1882. Carling born in Liverpool, England, in 1857, one of six children born to Henry and Rose Carling. His parents had been evicted from their tenant farm in Roscommon, Ireland, during the Potato Famine and moved to Liverpool where they lived in poverty. Little James began to work at five years old, busking, reciting Shakespeare on the street, doing whatever errands he could get paid to do.

The Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, is the proud owner of a little-known and seldom-seen collection of illustrations for Edgar Allen Poe’s 1845 masterpiece The Raven drawn by artist James Carling in 1882. Carling born in Liverpool, England, in 1857, one of six children born to Henry and Rose Carling. His parents had been evicted from their tenant farm in Roscommon, Ireland, during the Potato Famine and moved to Liverpool where they lived in poverty. Little James began to work at five years old, busking, reciting Shakespeare on the street, doing whatever errands he could get paid to do.

His true vocation was drawing. His brothers had taken up chalk drawing on the pavement for change and James watched their work, learning from it. When he was five, his brother Johnny gave him some paints and crayons. The next day James drew two famous prize-fighters on a flagstone on Ranelagh Street and received much positive reinforcement from passersby who were charmed by the talented little boy and tossed coins in his hat. Thus “The Little Chalker” was born.

He became a proficient artist and learn to work very quickly since he had often had to scram when the police came around. Here’s a description in his own words of the hard knock life of the six-year-old pavement artist in 1863 Liverpool:

He became a proficient artist and learn to work very quickly since he had often had to scram when the police came around. Here’s a description in his own words of the hard knock life of the six-year-old pavement artist in 1863 Liverpool:

Like James Street and the Exchange, Ranelagh St. was not free from the presence of the policeman. The last mentioned individual beat me from the crowding pavement and often tried to have me imprisoned for disregarding his warnings but I laughed at his threats. I knew by practice I was too small to be incarcerated, for I was often arrested — mark it, a boy of six arrested for drawing pavement pictures — and taking their brutal beatings as a matter of course, I drew my pictures, preferring a bloody face and a bruised limb to inaction and death by starvation.

On Christmas Eve, 1865, when he had just turned eight years old, he did not scram fast enough. He was arrested, jailed overnight and sentenced on Christmas Day to a week in the workhouse. After the week was up, the court committed him to St. George’s Industrial School for Boys where he remained for six years. There he learned to read and write and was treated with kindness by the headmaster, Monsignor James Nugent. His mother had died the year before his commitment and his father, who had refused to pay his son’s compelled tuition and been jailed for it, died while he was at school. As soon as he was released at the age of 14, James and his brother Henry left the country and moved to the United States.

The Carling brothers picked up in Philadelphia where they had left off, making street art for spare change. They did chalk pavement drawings in the beginning, and then joined a vaudeville troupe. James Carling would do portraits and caricatures while on stage, billing himself as the “Lightning Caricaturist” and “the Fastest Drawer in the World.” He traveled the country with the early musical variety spectacular The Black Crook. In 1880 he moved to Chicago where Henry had founded an art school.

James was in Chicago when he read about a competition in Harper’s magazine to illustrate a special edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven Harper & Brothers was going to publish. James loved Poe, considering him the “greatest poet this world has ever seen.” He made 43 illustrations, entering 33 of them in the contest. In 1883, Harper’s announced the surprise winner of this competition: Gustave Doré. Doré was hugely famous as the premiere print-maker and illustrator of the era, so basically this “competition” was a publicity stunt to get buzz for an expensive luxury edition of Poe’s poem, an edition they modestly described as “the most magnificent book of the year and in many cardinal particulars the most superb volume that has ever issued from the press of this or any other country.” Project Gutenberg has digitized this book, complete with illustrations.

James was in Chicago when he read about a competition in Harper’s magazine to illustrate a special edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven Harper & Brothers was going to publish. James loved Poe, considering him the “greatest poet this world has ever seen.” He made 43 illustrations, entering 33 of them in the contest. In 1883, Harper’s announced the surprise winner of this competition: Gustave Doré. Doré was hugely famous as the premiere print-maker and illustrator of the era, so basically this “competition” was a publicity stunt to get buzz for an expensive luxury edition of Poe’s poem, an edition they modestly described as “the most magnificent book of the year and in many cardinal particulars the most superb volume that has ever issued from the press of this or any other country.” Project Gutenberg has digitized this book, complete with illustrations.

James Carling thought Doré was great and all, but his own drawings were closer to Poe’s spirit. He wrote:

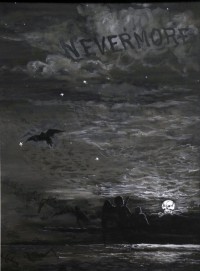

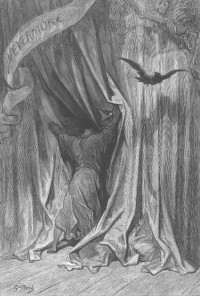

“Concerning ‘The Raven,’ I have been ‘dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.’ As well as Doré, I have illustrated ‘The Raven.’ Our ideas are as wide as the poles. Doré’s are beautiful; there is a tranquil loveliness in them unusual to Doré. Mine are stormier, wilder and more weird; they are horrible; I have reproduced mentality and phantasm. Not one of the ideas were ever drawn before. I feel that Poe would have said that I have been faithful to his idea of ‘The Raven,’ for I have followed his meaning so close as to be merged into his individuality.”

I quite agree with him. Compare the two styles, Carling on the left, Doré on the right:

In 1887, James returned to Liverpool, possibly planning on enrolling in the National School of Art. He fell ill and was admitted to the Brownlow Hill Workhouse on June 17th. Less than a month later, on July 9th, 1887, James Carling died at the age of 29. He was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave with 15 other people in what is today the Liverpool Parish Cemetery. His childhood spent dodging police beatings garnered him immortality, however. He is first named pavement artist whose life is fully documented and in his honor The James Carling International Pavement Art Competition takes place in Liverpool every year on Bold Street, about which he said in his unpublished autobiography “I not only could not draw in that street, I could not walk in it.”

His brother Henry kept James’ Raven illustrations for more than 50 years, finally putting them some of them on public display in a 1930 exhibit of his own work. They were very well received. Henry died six years later and the Poe Museum was delighted to purchase the complete set from Henry’s daughter Stella in 1937.

The illustrations spent four decades on display in the museum’s Raven Room, where they inspired a young Kevin Williamson who would grow up to become the screenwriter of the Scream movies and the current serial killer themed TV show The Following, but in 1975 curators decided their condition had dangerously deteriorated and for their own protection they had to be put in storage.

The illustrations spent four decades on display in the museum’s Raven Room, where they inspired a young Kevin Williamson who would grow up to become the screenwriter of the Scream movies and the current serial killer themed TV show The Following, but in 1975 curators decided their condition had dangerously deteriorated and for their own protection they had to be put in storage.

The 43 watercolour and ink illustrations have been damaged from exposure to light and moisture, and from having been glued to an acidic cardboard backing which has caused the paper to darken over time. To preserve these delicate works, the Poe Museum has launched a Kickstarter project with the goal of raising $60,000 by November 15th.

The money will go to conserving each of the 43 illustrations, replacing the cardboard backing with archival quality acid-free mat and addressing condition issues on a case-by-case basis. Once stabilized, the drawings will be professionally photographed in high resolution and the photographs sent on a traveling exhibition. A significant portion of the funds raised will go to publish all of Carling’s illustrations in a book. Backers of the Kickstarter project will be offered a chance to buy the book at a discounted rate.

Too bad he died so young, I would love to see what he would have come up with for pretty much anything by HP Lovecraft.

Thanks for sharing this story and how we can help through the Kickstarter campaign.