The wreck of the City of Chester, a steamship that sank with much loss of life in August 22, 1888, has been rediscovered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The ship was found in May of last year during a sonar survey of another shipwreck. The Office of Coast Survey Navigational Response Team 6 was scanning the wreck of the Fernstream, a freighter that went down in 1952. While they were in the neighborhood, NOAA director of maritime heritage James Delgado asked the team to look for the City of Chester.

The wreck of the City of Chester, a steamship that sank with much loss of life in August 22, 1888, has been rediscovered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The ship was found in May of last year during a sonar survey of another shipwreck. The Office of Coast Survey Navigational Response Team 6 was scanning the wreck of the Fernstream, a freighter that went down in 1952. While they were in the neighborhood, NOAA director of maritime heritage James Delgado asked the team to look for the City of Chester.

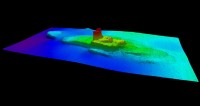

After working with historic data provided by NOAA historians, the Coast Survey team conducted a multi-beam sonar survey and a sonar target the right size and shape was found. The team spent nearly nine months sorting through the data. A follow-up side-scan sonar survey confirmed that the target was City of Chester, sitting upright, shrouded in mud, 216 feet deep at the edge of a small undersea shoal. High-resolution sonar imagery clearly defined the hull, rising some 18 feet from the seabed, and the fatal gash on the vessel’s port side.

The wreck won’t be salvaged or interfered with in any way –it’s a protected grave site owned by the state of California — but its rediscovery will be a central feature of an upcoming exhibition at the historic Coast Guard Station on Crissy Field, on the northeast shore of the Presidio.

The story of the City of Chester provides a glimpse into a fraught period in US, particularly California, history. Headed for Eureka, California, the steamship hit a fog bank on its way out of San Francisco Bay. It slowed down and sounded the whistle at regular intervals to alert any other ships in the area and soon received a whistle response from another ship, the Oceanic, a steamship twice Chester‘s size. According to news accounts of the shipwreck, Oceanic sent a double whistle signal, indicating the ships should pass each other on the starboard side, and the Chester acknowledged with a double whistle reply. However, the Chester, either because the signals were misunderstood or because the tides drove it off-course, made for the port side of Oceanic.

The story of the City of Chester provides a glimpse into a fraught period in US, particularly California, history. Headed for Eureka, California, the steamship hit a fog bank on its way out of San Francisco Bay. It slowed down and sounded the whistle at regular intervals to alert any other ships in the area and soon received a whistle response from another ship, the Oceanic, a steamship twice Chester‘s size. According to news accounts of the shipwreck, Oceanic sent a double whistle signal, indicating the ships should pass each other on the starboard side, and the Chester acknowledged with a double whistle reply. However, the Chester, either because the signals were misunderstood or because the tides drove it off-course, made for the port side of Oceanic.

They were already just half a mile apart when they became aware of each other’s presence; there was no time to avoid disaster. Oceanic plowed into the smaller ship, impaling it on its bow. The impact knocked some passengers directly into the water. Others were pulled up onto the Oceanic from the Chester deck. A few people were able to make it onto boats launched by the Chester in the six minutes it was still above the water after the collision. Oceanic sent down rescue boats of its own and threw life preservers to the survivors struggling in the cold, rough waters of the bay. Out of the 106 passengers and crew on the Chester manifest, 16 died, two of them small children.

It was the worst loss of life in the San Francisco Bay until 1901 when the City of Rio de Janeiro hit a reef and 128 people were lost. Because the Oceanic was coming from Japan and had some Asian crew (judging from the names, the officers were all Anglo) and because the question of Chinese immigration was on fire in the 1880s, there was some ugly racial commentary in the wake of the tragedy. John Walker, an able seaman (that’s a position, not a value judgment) on the Chester who was the first to emerge on the wharf after his rescue, told reporters:

It was the worst loss of life in the San Francisco Bay until 1901 when the City of Rio de Janeiro hit a reef and 128 people were lost. Because the Oceanic was coming from Japan and had some Asian crew (judging from the names, the officers were all Anglo) and because the question of Chinese immigration was on fire in the 1880s, there was some ugly racial commentary in the wake of the tragedy. John Walker, an able seaman (that’s a position, not a value judgment) on the Chester who was the first to emerge on the wharf after his rescue, told reporters:

“On the Oceanic the Chinese crew seemingly became terror-stricken as soon as the accident occurred, and much time was lost in the lowering boats of the latter steamer. If the crew had been white, there would have been more lives saved. Finally the boats of the Oceanic were lowered and did good work picking up those who were floating in the bay, sustaining themselves on life-preservers and bits of wreckage.”

That wasn’t necessarily the dominant narrative, however. Several articles credit the courage of a Chinese passenger on the Oceanic who rescued a little girl from the waves and held her, sitting astride a capsized lifeboat, until help came. Here’s a particularly telling account in the Sacramento Daily Record-Union of August 24, 1888:

A GALLANT CHINAMAN.

How a Mongolian Sailor Rescued a Baby from a Watery Grave

The conduct of Ah Lun, the Chinese sailor spoken of by Captain Metcalf as the rescuer of a little baby, is described by those who saw the incident as courageous in the extreme. Ah Lun was in a boat with three other Mongolians, and among the debris he discovered the head of a child. Throwing down his oar, he dived in after the little one, and then, after swimming for some distance, succeeded in reaching her. A few strokes brought him to the boat, which had been capsized in the whirlpool formed by the sinking steamer, and, climbing on the keel, he placed the child in such a position that the salt water was forced out of her mouth.

A few moments afterward he was taken off and brought on deck, where a mother was waiting to claim the little one. It was then discovered that Ah Lun had sustained many bruises and lacerations, his legs and arms being cut and scratched severely.

Deputy Surveyor Fogarty was specially delighted with the conduct of the Chinaman, who it appears, is an old acquaintance of his. When the urbane Deputy reached the deck the Chinaman accosted him, and after receiving his congratulations asked if he did not think he ought to be allowed to go on shore, though he was not a certificated man. Fogarty assured him that if it was in his power to let him, he would be made an American citizen without delay.

“If ever a Mongolian deserved to be habeased corpused,” said Mr. Forgarty to a Call reporter, “I think Ah Lun is the man.”

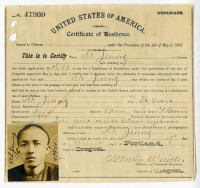

Ah Lun not being a “certificated man” who nonetheless deserves to be “habeased corpused” is a reference the legal chaos that followed the United States’ first law blocking one particular ethnic group from immigration: the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The act prohibited Chinese laborers, skilled and unskilled, and miners from entering the country for 10 years. Only a few categories of professionals like merchants were allowed entry, and they had to secure a “section 6 certificate” from the Chinese government attesting to their occupation. Chinese immigrants who already lived in the United States were prohibited entry to the US without an identity document known as a return certificate. It also excluded Chinese immigrants from applying for US citizenship.

Ah Lun not being a “certificated man” who nonetheless deserves to be “habeased corpused” is a reference the legal chaos that followed the United States’ first law blocking one particular ethnic group from immigration: the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The act prohibited Chinese laborers, skilled and unskilled, and miners from entering the country for 10 years. Only a few categories of professionals like merchants were allowed entry, and they had to secure a “section 6 certificate” from the Chinese government attesting to their occupation. Chinese immigrants who already lived in the United States were prohibited entry to the US without an identity document known as a return certificate. It also excluded Chinese immigrants from applying for US citizenship.

In practice, enforcing this law was a monster problem for the courts. The Act contradicted the terms of an 1880 treaty between China and the United States, and there were thousands of people who fell through the cracks of the return certificate system. If they were out of the country, traveling back home to see family, perhaps, when the law was passed, then obviously there was no way for them to have secured the return certificate or the section 6 certificate before it was invented.

With anti-Chinese sentiment so thoroughly entrenched in San Francisco politics, the collector of the port, the political appointee responsible for enforcing the Exclusion Act, denied entry to anyone lacking the certificates, even if securing them was a complete impossibility short of inventing a time machine. When they were refused entry into San Francisco, the Chinese filed writs of habeas corpus in federal court on the grounds that they were being illegally detained on their ships.

So that’s what Ah Lun was talking about when he asked Fogarty if he could be allowed on shore despite not being a “certificated man,” and when Fogarty said he deserved to be “habeased corpused,” or released from confinement aboard ship so he could return to his San Francisco home. As the deputy surveyor, Fogarty would have had some involvement in these court cases. The surveyor and deputy surveyor were part of the U.S. Attorney’s team in at least one very high-profile habeas corpus writ which eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court. It was ultimately decided in favor of the petitioner, Chew Heong, on treaty grounds and because he had left the country in 1881, before the Act was passed. The decision also confirmed the citizenship of anyone born in the United States, including the children of Chinese immigrants.

So that’s what Ah Lun was talking about when he asked Fogarty if he could be allowed on shore despite not being a “certificated man,” and when Fogarty said he deserved to be “habeased corpused,” or released from confinement aboard ship so he could return to his San Francisco home. As the deputy surveyor, Fogarty would have had some involvement in these court cases. The surveyor and deputy surveyor were part of the U.S. Attorney’s team in at least one very high-profile habeas corpus writ which eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court. It was ultimately decided in favor of the petitioner, Chew Heong, on treaty grounds and because he had left the country in 1881, before the Act was passed. The decision also confirmed the citizenship of anyone born in the United States, including the children of Chinese immigrants.

Even as more amendments were tacked on to the Exclusion Act to make it ever more exclusionary, the habeas corpus petitions kept coming, so much so that they clogged the docket of federal judges and ground the system to a near-halt. By the end of the decade, more than 7,000 habeas corpus writs had been filed in the California district court alone.

In 1888, the Chinese government, sick of the treaty violations and horrified by violence against Chinese immigrant communities like the 1885 Rock Springs massacre in which 28 Chinese miners were killed and hundreds forced to flee for their lives by a mob of 150 white miners and railroad workers, negotiated a new treaty with the US. The Bayard-Zhang Treaty of March, 1888, prohibited immigration or return of Chinese laborers for 20 years. The only exceptions were for people who had assets of at least $1,000 or immediate family living in the US.

In 1888, the Chinese government, sick of the treaty violations and horrified by violence against Chinese immigrant communities like the 1885 Rock Springs massacre in which 28 Chinese miners were killed and hundreds forced to flee for their lives by a mob of 150 white miners and railroad workers, negotiated a new treaty with the US. The Bayard-Zhang Treaty of March, 1888, prohibited immigration or return of Chinese laborers for 20 years. The only exceptions were for people who had assets of at least $1,000 or immediate family living in the US.

The treaty was not well-received in China, and the government began to back away from ratification unless the chains were loosened a little bit. Meanwhile, it still wasn’t draconian enough for the Americans, so in October of 1888, Congress passed the Scott Act, a supplement to the Exclusion Act that locked the door tight.

Terms of Scott Act:

SEC. 1. It shall be unlawful for any chinese laborer who shall at any time heretofore have been, or who may now or hereafter be, a resident within the United States, and who shall have departed, or shall depart, therefrom, and shall not have returned before the passage of this act, to return to, or remain in, the United States.

SEC. 2. That no certificates of identity . . . shall hereafter be issued; and every certificate heretofore issued in pursuance thereof, is hereby declared void and of no effect, and the chinese laborer claiming admission by virtue thereof shall not be permitted to enter the United States.

When the Scott Act came before the Supreme Court the next year, the decision went entirely the opposite way from the 1884 case. It was unanimously upheld. Chinese Exclusion continued to be the law of the land, with regular amendments over the years, until World War II.

The reference to the Rock Springs massacre really got to me – I grew up there in the ’60s, including attending junior high and high school, and I don’t recall any mention of that incident at all. Perhaps it’s not surprising that it wasn’t featured in our civics or history classes, in that it was a truly appalling and shameful affair, but I don’t think that such atrocities should be forgotten.

By the time I lived there the town had begun to celebrate the 50+ different nationalities, including Chinese, that had contributed to its population, and I’d always thought fondly of this, but I admit that reading about the massacre puts a different complexion on things…

I think there are many places that have yet to come to terms with some of their ugliest history. At first they just don’t care and then they stop talking about it and it sort of fades away. Perhaps now that Rock Springs appreciates its diversity, it should take a good, hard look at the past in an open, public, unflinching way.