It began with the peineta, the tall comb worn by Spanish women under the mantilla, a traditional translucent lace head covering, or by flamenco dancers as decorative hairpieces. Aspects of the comb tradition go back hundreds of years, but the accessory as we know it today took root in the 18th century and came to its full fulgor in the early 19th century. It crossed the Atlantic, establishing itself in Spanish Latin America where it soon took on a unique character.

It began with the peineta, the tall comb worn by Spanish women under the mantilla, a traditional translucent lace head covering, or by flamenco dancers as decorative hairpieces. Aspects of the comb tradition go back hundreds of years, but the accessory as we know it today took root in the 18th century and came to its full fulgor in the early 19th century. It crossed the Atlantic, establishing itself in Spanish Latin America where it soon took on a unique character.

This was a turbulent time for Spain’s old colonies. Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808 and while the motherland poured money and might into the fight for the next six years, the colonies struggled for their own independence and the Empire splintered under the pressure. As independence movements grew, Latin American fashions followed, branching off into their own distinctive development.

They had the raw materials for it: the shells of Caribbean sea turtles. They were widely traded in South America, used by artisans to craft jewelry and decorative items like hair combs. With an embarrassment of riches purloined from what seemed like an inexhaustible supply of marine turtles (not coincidentally, they’re endangered now), artists could expand the boundaries of the traditional design.

In 1823, Spanish machinist Manuel Mateo Masculino started a business in Buenos Aires making combs and comb-making machines. He advertised that his gear and employees could produce more than a thousand combs a day. His business took off. Soon he had 106 employees making his designs using three different kinds of turtle shells (including a very expensive Indian import), ivory and mother of pearl. The material was cut, punctured, carved, polished, stamped, embossed, heat fused and polished. Masculino’s machines and the templates he designed brought a whole new complexity to the peineta, creating elaborate openwork filigree in place of the more solid edged Spanish pieces.

In 1823, Spanish machinist Manuel Mateo Masculino started a business in Buenos Aires making combs and comb-making machines. He advertised that his gear and employees could produce more than a thousand combs a day. His business took off. Soon he had 106 employees making his designs using three different kinds of turtle shells (including a very expensive Indian import), ivory and mother of pearl. The material was cut, punctured, carved, polished, stamped, embossed, heat fused and polished. Masculino’s machines and the templates he designed brought a whole new complexity to the peineta, creating elaborate openwork filigree in place of the more solid edged Spanish pieces.

He also went big, not home, expanding the Spanish originals into combs one foot square. Every year his designs got bigger and fancier. The original wedge shape morphed into crescents, crowns, bell shapes, baskets. By the early 1830s, the average width was three feet. No longer were they peinetas. Now they were peinetones.

The massive combs and the ladies who wore them were cause for much comment in the media. They became socio-political footballs, representing the evils of female vanity and wastefulness and the rejection of the ideal of the modest virtues of the household. Journalists tut-tutted at their impracticality; poets wrote verse imprecations against women who bankrupted their families and turned to prostitution to support their

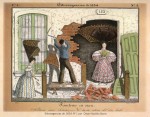

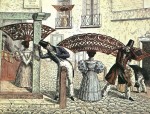

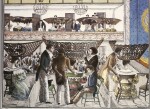

The massive combs and the ladies who wore them were cause for much comment in the media. They became socio-political footballs, representing the evils of female vanity and wastefulness and the rejection of the ideal of the modest virtues of the household. Journalists tut-tutted at their impracticality; poets wrote verse imprecations against women who bankrupted their families and turned to prostitution to support their  peineton habit; artists satirized the increasingly absurd dimensions. A series of lithographs by French artist César Hipólito Bacle published in a magazine called Extravagancias de 1834 caricatured the giant hair combs as literal homewreckers, knocking down walls on their way out, assaulting men on the street and ruining their view at the theater.

peineton habit; artists satirized the increasingly absurd dimensions. A series of lithographs by French artist César Hipólito Bacle published in a magazine called Extravagancias de 1834 caricatured the giant hair combs as literal homewreckers, knocking down walls on their way out, assaulting men on the street and ruining their view at the theater.

The National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires has two exceptional examples from its collection online which prove the satires had a kernel of truth. This piece is a fraction of an inch under three feet wide and just over one foot high. It’s modest compared to this beautiful behemoth which is three feet ten inches wide and one foot four inches high. The elegant lady who wore that didn’t knock down walls, but she definitely had to walk through doors sideways.

The National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires has two exceptional examples from its collection online which prove the satires had a kernel of truth. This piece is a fraction of an inch under three feet wide and just over one foot high. It’s modest compared to this beautiful behemoth which is three feet ten inches wide and one foot four inches high. The elegant lady who wore that didn’t knock down walls, but she definitely had to walk through doors sideways.

Notice in the center of that comb is a carved silhouette of Juan Manuel de Rosas, military leader and Federalist governor (read: dictator) of the province of Buenos Aires who ruled from 1829 until 1852, covering the heyday of the peineton. The oval is surrounded by oak leaves, a nod to the high Roman military decoration the corona civica, and topped with a Phrygian cap, a symbol of liberty. Underneath the oak wreath is carved the slogan “Federation or Death,” which helps date the hairpiece to 1832 at the earliest, the year de Rosas decreed that that phrase be used in all federal badges. There are few surviving examples of this slogan in a fashionable accessory.

Notice in the center of that comb is a carved silhouette of Juan Manuel de Rosas, military leader and Federalist governor (read: dictator) of the province of Buenos Aires who ruled from 1829 until 1852, covering the heyday of the peineton. The oval is surrounded by oak leaves, a nod to the high Roman military decoration the corona civica, and topped with a Phrygian cap, a symbol of liberty. Underneath the oak wreath is carved the slogan “Federation or Death,” which helps date the hairpiece to 1832 at the earliest, the year de Rosas decreed that that phrase be used in all federal badges. There are few surviving examples of this slogan in a fashionable accessory.

By the time Bacle’s Extravagancias came out, Rosas had turned on the peinetones. Once symbols of Argentine patriotism, a way for women to display their support for Argentine independence in the public sphere, the huge combs were now dangerously subversive, as far as the government was concerned. Bacle ran the official government press, so he wasn’t just printing a fashion magazine. He was actively working on Rosas’ behalf to associate the peineton with women of questionable virtue and even more questionable politics.

By the time Bacle’s Extravagancias came out, Rosas had turned on the peinetones. Once symbols of Argentine patriotism, a way for women to display their support for Argentine independence in the public sphere, the huge combs were now dangerously subversive, as far as the government was concerned. Bacle ran the official government press, so he wasn’t just printing a fashion magazine. He was actively working on Rosas’ behalf to associate the peineton with women of questionable virtue and even more questionable politics.

It worked. The trend toward giantism reversed, and even though peinetones remained in fashion through the 1850s, the day of the four-footer was over.

Suddenly the young men with ordinary combs stuck in their afros look a lot more mundane.

Doña Isabella 1 : Argentina 0

I think there pretty

Argentinian newspapers might have caricatured the giant hair combs as homewreckers with dangerous weapons assaulting men on the street, but were the big combs ever banned?

Edwardian courts actually banned long hat pins worn by suffragettes and their contemporaries because they were afraid women would use the long metal shaft as a weapon against men!

sorry. I forgot my name.

Hels

Art and Architecture, mainly

Humans! :no:

You always have such interesting posts! I can’t imagine the time it must take for the research, the writing, and the photos. I check your blog nearly every day to see what’s new. Thanks!

You can’t make up stuff like this…! In regard to the history of fashion, it is worth noting that in the 1820s, skirts were beginning to widen (moving on from the closer “Empire and after” silhouette), leading into fairly massive hoops and crinolines in the ’40s and ’50s. By the 1830s (as documented in the prints) enhanced sleeves and shoulders were appearing to balance the bigger skirts–and the development of the peinetones would have paralleled this (while maintaining a distinct local character–to put it mildly!)