The Metropolitan Museum of Art has stepped in to save an ancient Egyptian collection of artifacts from dispersal into the auction void. The Treasure of Harageh, a group of Twelfth Dynasty jewelry and travertine vessels excavated in 1913-14 from Tomb 124 at Harageh near the city of Faiyum in Middle Egypt, was supposed to go under the hammer at the Bonhams Antiquities sale on October 2nd. At the last minute, the lot was withdrawn and Bonhams announced it had negotiated a private sale for an undisclosed amount to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has stepped in to save an ancient Egyptian collection of artifacts from dispersal into the auction void. The Treasure of Harageh, a group of Twelfth Dynasty jewelry and travertine vessels excavated in 1913-14 from Tomb 124 at Harageh near the city of Faiyum in Middle Egypt, was supposed to go under the hammer at the Bonhams Antiquities sale on October 2nd. At the last minute, the lot was withdrawn and Bonhams announced it had negotiated a private sale for an undisclosed amount to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This was a happy result for a controversial sale. The controversy wasn’t the usual kind. There was no trumped up “Swiss private collection” provenance; the ownership history was clear and unblemished, the publication record extensive. It was the seller raising eyebrows: the American Institute for Archaeology’s St. Louis Society. The AIA is opposed on principle to the sale of antiquities, believing they belong in the care of experts who will conserve them and make them available to the public for educational purposes. The St. Louis Society is an independent non-profit, however, and its charter with the AIA only explicitly prohibits the sale or purchase of undocumented artifacts, so no matter how horrified the national organization was, it could not prevent the sale.

This was a happy result for a controversial sale. The controversy wasn’t the usual kind. There was no trumped up “Swiss private collection” provenance; the ownership history was clear and unblemished, the publication record extensive. It was the seller raising eyebrows: the American Institute for Archaeology’s St. Louis Society. The AIA is opposed on principle to the sale of antiquities, believing they belong in the care of experts who will conserve them and make them available to the public for educational purposes. The St. Louis Society is an independent non-profit, however, and its charter with the AIA only explicitly prohibits the sale or purchase of undocumented artifacts, so no matter how horrified the national organization was, it could not prevent the sale.

![]() The artifacts have belonged to the St. Louis Society since they were first excavated by a British School of Archaeology team led by Reginald Engelbach under the direction of pioneering archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie. The Society helped fund the excavation. In return, they received this exceptional group of artifacts. There are five travertine objects, four of them vessels, one of them a cosmetic spoon with a handle in the shape of an ankh. The jewelry group is seven cowrie shell-shaped pendants made of silver, a rare material worth more than gold in the Middle Kingdom, 14 real sea shell pendants mounted in silver and 11 silver pieces inlaid with various hardstones that probably were part of a pectoral plaque.

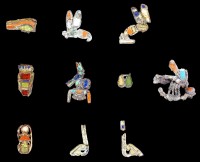

The artifacts have belonged to the St. Louis Society since they were first excavated by a British School of Archaeology team led by Reginald Engelbach under the direction of pioneering archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie. The Society helped fund the excavation. In return, they received this exceptional group of artifacts. There are five travertine objects, four of them vessels, one of them a cosmetic spoon with a handle in the shape of an ankh. The jewelry group is seven cowrie shell-shaped pendants made of silver, a rare material worth more than gold in the Middle Kingdom, 14 real sea shell pendants mounted in silver and 11 silver pieces inlaid with various hardstones that probably were part of a pectoral plaque.

It’s the 11 pectoral pieces that date the artifacts. Individual pieces are designed as hieroglyphs that spell the name of Pharoah Senusret II, the fourth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty who ruled from 1897-1878 B.C. One of the 11 is also the standout piece of the collection. It’s a unique jewel in the shape of a bee. What makes it unique is that it’s three-dimensional, with inlays on both sides and even visible from the top. There is no other 3D jewel known from the Middle Kingdom. The bee, the real shell pendants (the first known instance of actual shells being used in Egyptian jewelry) and the ankh spoon are all unique and of major historical significance.

It’s the 11 pectoral pieces that date the artifacts. Individual pieces are designed as hieroglyphs that spell the name of Pharoah Senusret II, the fourth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty who ruled from 1897-1878 B.C. One of the 11 is also the standout piece of the collection. It’s a unique jewel in the shape of a bee. What makes it unique is that it’s three-dimensional, with inlays on both sides and even visible from the top. There is no other 3D jewel known from the Middle Kingdom. The bee, the real shell pendants (the first known instance of actual shells being used in Egyptian jewelry) and the ankh spoon are all unique and of major historical significance.

For many years the collection was kept at the St. Louis Art Museum. In 2011 it was moved to Washington University in St. Louis and two years ago it wound up in private storage at a cost of $2,000 a year. It was that storage fee and the conservation challenge that drove the St. Louis Society to sell the Treasure of Harageh. Howard Wimmer, secretary of the St. Louis Society, said: “If there had been any way that we could have reasonably kept these items in St. Louis, we never would have pursued this course. One way or the other, we had to find a new home.”

For many years the collection was kept at the St. Louis Art Museum. In 2011 it was moved to Washington University in St. Louis and two years ago it wound up in private storage at a cost of $2,000 a year. It was that storage fee and the conservation challenge that drove the St. Louis Society to sell the Treasure of Harageh. Howard Wimmer, secretary of the St. Louis Society, said: “If there had been any way that we could have reasonably kept these items in St. Louis, we never would have pursued this course. One way or the other, we had to find a new home.”

It’s that one way they chose that was the sticking point. The AIA might not have had grounds to block the sale, but it wasn’t the only interested party.

Alice Stevenson, curator of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London, said a sale to a private buyer would have violated an agreement between the museum’s namesake explorer and the St. Louis group that the antiquities be distributed to public museums, accessible to both researchers and the public.

“Museums and archaeologists are stewards of the past,” she said. “They should not sell archaeological items in their collections for profit.”.

Thanks to the Met, which is glad to join this treasure to other Harageh artifacts in its permanent collection, the sale of these antiquities won’t see them dispersed contextless into private collections out of the reach of the public and scholars. Unfortunately, there was one lot from the St. Louis Society’s Harageh artifacts, a Tenth-Eleventh Dynasty travertine head rest (2150-1990 B.C.) that did not get an eleventh hour reprieve. It sold to an unknown buyer for £27,500 ($44,182). I wonder if the Petrie Museum is aware of this sale. It seems like they might have legal grounds to void it.

Thanks to the Met, which is glad to join this treasure to other Harageh artifacts in its permanent collection, the sale of these antiquities won’t see them dispersed contextless into private collections out of the reach of the public and scholars. Unfortunately, there was one lot from the St. Louis Society’s Harageh artifacts, a Tenth-Eleventh Dynasty travertine head rest (2150-1990 B.C.) that did not get an eleventh hour reprieve. It sold to an unknown buyer for £27,500 ($44,182). I wonder if the Petrie Museum is aware of this sale. It seems like they might have legal grounds to void it.