A late 16th portrait of King Henry III of France that has been missing from the Louvre since World War II was discovered about to go up for auction in Paris. A small work at eight by five inches, the painting was valued by the Ader-Nordmann auction house at only €400-€600 ($505-$758). One week before the October 17th auction, Pierre-Gilles Girault, assistant curator of the Royal Château de Blois, found out about the sale from a Henry III keyword alert he’d set up on a public auction search site.

A late 16th portrait of King Henry III of France that has been missing from the Louvre since World War II was discovered about to go up for auction in Paris. A small work at eight by five inches, the painting was valued by the Ader-Nordmann auction house at only €400-€600 ($505-$758). One week before the October 17th auction, Pierre-Gilles Girault, assistant curator of the Royal Château de Blois, found out about the sale from a Henry III keyword alert he’d set up on a public auction search site.

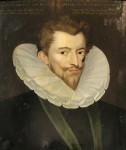

The Château de Blois played a dramatic role in the bloody intrigues of Henry’s turbulent reign, and in 2010 the museum held an exhibition dedicated to the period, Renaissance celebrations and crimes, the Court of Henry III. When Girault saw the painting for sale, he recognized its rare iconography of Henry on his knees at the foot of the Cross and its unusual medium — oil on paper mounted on panel — as a work he had seen in a 1930s-era catalogue of the Louvre collection. The size was slightly different, however, so he thought it might be a contemporary copy. The museum was still interested in acquiring it to expand its Henry III materials. Even a copy of a realistic portrait of a king, whose life and reign were mired in Wars of Religion, depicted in such a heavy-handedly devout posture could well be worth the small purchase price. There are very few extant realistic portraits of Henry III, and they’re standard court paintings. This one ties Henry directly into the defining issue of his reign and of 16th century France.

Although as Duke of Anjou the Catholic Henry had played a major role fighting the Protestants in the French Wars of Religion — he was the leader of the army, defeating Hugenots forces in several battles and besieging the Hugenot city of La Rochelle — when he became king after the death of his older brother Charles IX, he took a more practical approach. With the Protestant army led by his younger brother François, formerly Duke of Alençon and now Duke of Anjou, besieging Paris, in 1576 Henry signed he Edict of Beaulieu which granted the Hugenots freedom of religion and major political concessions.

Although as Duke of Anjou the Catholic Henry had played a major role fighting the Protestants in the French Wars of Religion — he was the leader of the army, defeating Hugenots forces in several battles and besieging the Hugenot city of La Rochelle — when he became king after the death of his older brother Charles IX, he took a more practical approach. With the Protestant army led by his younger brother François, formerly Duke of Alençon and now Duke of Anjou, besieging Paris, in 1576 Henry signed he Edict of Beaulieu which granted the Hugenots freedom of religion and major political concessions.

Henry I, Duke of Guise, didn’t take kindly to that. He formed the Catholic League, a coalition of French Catholic societies supported by the Pope and Philip II of Spain, to apply military and political pressure in favor of the eradication of the Hugenots. His efforts were very successful. Henry III was forced to fight both Protestants and Catholics arrayed against him, and he just didn’t have the wherewithal to pull it off. He was forced to roll back the concessions in the Edict of Beaulieu and Peace of La Rochelle and give the League everything it asked for, including that the king pay its troops. From the Treaty of Nemours in 1585 through the end of 1588, Henry was king in name only. For a short while the Duke of Guise even took Paris, forcing Henry III to flee to the royal palace at Blois in May of 1588.

Henry I, Duke of Guise, didn’t take kindly to that. He formed the Catholic League, a coalition of French Catholic societies supported by the Pope and Philip II of Spain, to apply military and political pressure in favor of the eradication of the Hugenots. His efforts were very successful. Henry III was forced to fight both Protestants and Catholics arrayed against him, and he just didn’t have the wherewithal to pull it off. He was forced to roll back the concessions in the Edict of Beaulieu and Peace of La Rochelle and give the League everything it asked for, including that the king pay its troops. From the Treaty of Nemours in 1585 through the end of 1588, Henry was king in name only. For a short while the Duke of Guise even took Paris, forcing Henry III to flee to the royal palace at Blois in May of 1588.

With his marriage childless, Anjou dead and his presumptive heir now the Protestant Henry, King of Navarre, Henry III had good reason to fear not just for his throne, but for his life. It was the defeat of the Spanish Armada in August of 1588 that weakened the Catholic League and emboldened Henry III. In September, Henry called a meeting of the Estates General at the Château de Blois. In December, he invited the Duke of Guise and his brother Louis II, Cardinal of Guise, to the council chamber. The Duke was directed to join Henry III in the adjoining bed chamber where he was set promptly set upon by Henry’s loyal bodyguards, the Forty-five, who stabbed him to death at the foot of the king’s bed. The next day, the Cardinal of Guise met a similar fate in the castle’s dungeon. Henry’s formidable mother Catherine de’ Medici, horrified at the assassinations, died two weeks later and was buried at Blois since Paris was still held by Guise’s men. (Her body was later moved to St. Denis and would ultimately suffer the fate of all the monarchs of France buried there when in 1793 a revolutionary mob looted the cathedral and threw all the royal remains in an unmarked mass grave.)

This is why the painting of Henry III that embeds him, monarchical ermines and all, praying on the ground with human bones in the center of the apex of Catholic iconography, the Crucifixion, held such interest for the Château de Blois museum. Chief curator Elisabeth Latrémolière, in accordance with standard museum acquisition protocols, sought out expert opinions on the piece. Girault emailed the Louvre’s 16th century art curator and received an immediate response even though it was Sunday. The Louvre sent its people to examine the painting in person, and on October 14th, they verified by comparing it to the sole known pre-loss photograph of the painting taken in 1925 that it was the original work, gone missing more than 70 years ago under mysterious circumstances.

Ader Nordmann immediately withdrew the work as soon as the Louvre experts authenticated it. It was being sold as part of the estate of an elderly woman; nobody had any idea how she had acquired it or what winding road took it from the Louvre to the auction. The painting will be returned to the Louvre posthaste, but Elisabeth Latrémollière hopes the museum will throw them a bone and lend them the portrait for display at the Château de Blois. After all, if it weren’t for the Blois curators, the painting would still be lost, an unknown budget purchase in someone’s private collection.

Maybe the unnamed elderly lady found it in a flea market for $7.00. It’s happened before!

Not seen since before the war, this painting was being sold as part of the estate of an individual. Perhaps in the chaos of Europe under war conditions, the painting was either stolen, or hidden for safety reasons and forgotten.

What a hideous bit of history. Henry invited the Duke of Guise and his brother Louis II, Cardinal of Guise, to the council chamber. The Duke was murdered on one day and the Cardinal of Guise was murdered the next day. Nasty 🙁

True BUT they were both traitors.

I think it was probably looted by one of the German officers who was going through the museums of Paris scrounging art, it was small and easily nicked from the official turn over of loot to whichever officer was rummaging and the enlisted man gave it to his French ‘collaborationist’ girlfriend who may have been the elderly lady because ‘here, you like this stuff,…’

I suspect the Ader-Nordmann’s appraiser has been encouraged to find another situation.

Also, the King Charles Spaniel in the murder painting looks out of place. Perhaps it’s an English spy? “Perfidious Albion” after all.

The painting from 1834 might also be an interesting one. Is there a reason why by 1834 poor Henry III should still have been an issue ? – Louis Philippe I, King of the French from 1830-48, is said to have survived seven assassination attempts: 19 Nov 1832, 28 Jul 1835, 25 Jun 1836, 27 Dec 1836, 15 Oct 1840, 16 Apr 1846 and 29 Jul 1846. After the events of 1848, however, he was forced to abdicate and went into exile again, this time as ‘Duc de Neuilly ‘ to a Château in England.

My artist’s eye notes odd details: like the fact that the dog, who looks for all the world as if he’s about to give chase to a rodent, has his nose pointed right at the artist’s signature. I also suspect that the artist resembles four or five of the guys hanging out in the bedchambre.