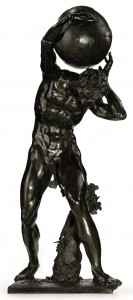

I love it when a museum wins an auction bidding war. The institution in question is the Rijksmuseum which has just bought Bacchic Figure Supporting the Globe, a bronze statue by Adriaen de Vries, for $27,885,000 including buyer’s premium at The Exceptional Sale in Christie’s New York saleroom. Three phone bidders engaged in a four-minute battle for the Mannerist masterpiece and the Rijksmuseum came out victorious thanks to generous funding from private and public donors.

I love it when a museum wins an auction bidding war. The institution in question is the Rijksmuseum which has just bought Bacchic Figure Supporting the Globe, a bronze statue by Adriaen de Vries, for $27,885,000 including buyer’s premium at The Exceptional Sale in Christie’s New York saleroom. Three phone bidders engaged in a four-minute battle for the Mannerist masterpiece and the Rijksmuseum came out victorious thanks to generous funding from private and public donors.

The price sets a new record for de Vries, eclipsing the previous record that was set in 1989 when The Dancing Fawn sold for £6.8 million ($10,687,560). That was the last time a major work by the artist went up for auction, so if the Rijksmuseum hadn’t committed to this purchase, who knows when the next opportunity would present itself to acquire a work by one of the greatest Dutch sculptors for the Netherlands Collection. The museum owns a small bronze relief Bacchus Finding Ariadne on Naxos (c. 1611) by de Vries, and it has a larger sculpture, Triton Blowing a Conch Shell (c. 1615 – c. 1618), on loan from the National Museum in Stockholm. Bacchic Figure Supporting the Globe, which the museum is calling simply Atlas, is the first major piece by de Vries in a public Dutch collection.

It’s a particularly fine specimen as well.

Dated 1626 and probably the last autograph work by De Vries the bronze represents the mythological figure of Atlas, a nude man supporting the globe. It displays the virtuoso and highly individual modelling style for which the sculptor was celebrated during his lifetime. This exceptionally sketchy, free and tactile style reached its apogee in the final years of his life and shows him as a true artistic innovator, centuries ahead of his time.

De Vries was born in The Hague around 1555 where he trained as a goldsmith before moving to Florence and working in the studio of Mannerist sculptor Giambologna, the Medici court sculptor, in 1581. In 1589, de Vries went to Prague by request of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, the greatest patron of the arts on the continent. In this first period of work for the emperor, he made two large bronze statues, Mercury Abducting Psyche, now in the Louvre, and Psyche Borne by Cupids, now in the Nationalmuseum Stockholm.

De Vries was born in The Hague around 1555 where he trained as a goldsmith before moving to Florence and working in the studio of Mannerist sculptor Giambologna, the Medici court sculptor, in 1581. In 1589, de Vries went to Prague by request of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, the greatest patron of the arts on the continent. In this first period of work for the emperor, he made two large bronze statues, Mercury Abducting Psyche, now in the Louvre, and Psyche Borne by Cupids, now in the Nationalmuseum Stockholm.

He then traveled back to Italy to study antiquities in Rome and on his way back made two monumental multi-figure fountains in Augsburg, Germany. In 1601 he was back in Prague where he worked for Rudolf II until the emperor’s death in 1612. Although he was still technically employed at court, Rudolf’s successor, his brother Matthias, does not appear to have commissioned any work from de Vries. The artist found other royal patrons in Germany, Austria and Denmark and continued to produce work until his death in 1626.

De Vries’ innovative approach to bronze casting, modelling and the use of patina to convey differences in color as well as texture made him hugely famous in his time. He created Atlas using the direct lost wax method which models a central wax core with the features of the final sculpture before wrapping it in a fire-resistant casing and heating it so the wax melts. Bronze is then poured into the casing and once it cools, the casing is broken off to reveal the sculpture. Naturally the process results in areas that need additional work — extra blobs of bronze to file off, holes filled, details enhanced — but Atlas appears to have been barely touched. Even the details in the vines on the base and the figure’s head are as de Vries designed them on the wax.

De Vries’ innovative approach to bronze casting, modelling and the use of patina to convey differences in color as well as texture made him hugely famous in his time. He created Atlas using the direct lost wax method which models a central wax core with the features of the final sculpture before wrapping it in a fire-resistant casing and heating it so the wax melts. Bronze is then poured into the casing and once it cools, the casing is broken off to reveal the sculpture. Naturally the process results in areas that need additional work — extra blobs of bronze to file off, holes filled, details enhanced — but Atlas appears to have been barely touched. Even the details in the vines on the base and the figure’s head are as de Vries designed them on the wax.

His talents earned Adriaen de Vries the sobriquet the Dutch Michelangelo, but the upheaval of the Thirty Years’ War and subsequent conflicts saw his works widely plundered and the memory of him in his homeland faded. The largest single collection of de Vries’ sculptures is in the Museum De Vries at Drottningholm Palace outside of Stockholm. They were all pillaged, most of them from Rudolf II’s collection by Swedish troops in the second Sack of Prague, the last battle of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, others from the Frederiksborg Palace in Denmark in 1659 during the Dano-Swedish War.

Atlas is one of few works by de Vries to have stayed put for 300 years or so, unpublished and unknown. Since it was one of the last sculptures he ever made, experts believe it was sold by his heirs after his death. The first time it appears in the record is in an engraving from around 1700 of the gardens of the Saint Martin Castle in Graz, Austria. Its path from Prague to Austria is unknown, but the sellers have among their illustrious line an ancestor named Margarethe Leopoldine, Countess Colonna von Fels, who married into the family. Her great-grandfather was Leonhard, Freiherr Colonna von Fels, a prominent Bohemian noble who had actually been present and involved in the famous 1618 Defenestration of Prague when two pro-Catholic Regents and a secretary were tossed out of a window by Bohemian Protestant nobles who justifiably feared the concessions granted them by HRE Matthias would be revoked. Margarethe was born many years later and married in 1693. By then statue would have been a family heirloom of several generations that she brought with her to Austria, perhaps as part of her dowry. She installed it in the courtyard of the family castle where it remained perched on a column until 2010.

Atlas is one of few works by de Vries to have stayed put for 300 years or so, unpublished and unknown. Since it was one of the last sculptures he ever made, experts believe it was sold by his heirs after his death. The first time it appears in the record is in an engraving from around 1700 of the gardens of the Saint Martin Castle in Graz, Austria. Its path from Prague to Austria is unknown, but the sellers have among their illustrious line an ancestor named Margarethe Leopoldine, Countess Colonna von Fels, who married into the family. Her great-grandfather was Leonhard, Freiherr Colonna von Fels, a prominent Bohemian noble who had actually been present and involved in the famous 1618 Defenestration of Prague when two pro-Catholic Regents and a secretary were tossed out of a window by Bohemian Protestant nobles who justifiably feared the concessions granted them by HRE Matthias would be revoked. Margarethe was born many years later and married in 1693. By then statue would have been a family heirloom of several generations that she brought with her to Austria, perhaps as part of her dowry. She installed it in the courtyard of the family castle where it remained perched on a column until 2010.

For a long time Adriaen de Vries was one of the secrets of art-history, a highly original genius, only know by a handful of insiders. The successful international exhibition devoted to the sculptor that the Rijksmuseum organised together with the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles in 1998-2000, has led to a wider appreciation of his bronzes and a revaluation of his reputation; nowadays he is considered as one of the most important sculptors of the early Baroque.

I want to ask what people think about the posts on these outsized bids for a few paintings costing millions and millions of dollars, and then the next post on begging the public for a few more dollars in donations on holding on to an artistic collection (this seems to be a UK issue especially; i never read about this in the USA, and I’m based in the USA).

i wonder there should be a UN artistic/historical fund, where the money helps to preserve the art collections, and are supported by some tax on these million dollars auctions. of course, it will never happen, but it should. i felt sad that museums and other public institutions have to beg for money to preserve some art pieces, while some art paintings are bought and sold as investment vehicles without any real thought given to their real contributions to society…

I agree with George. If a country wants to preserve culture and important pieces of art, there must be some kind of fund with resources available for purchasing certain pieces. Speaking about value, maybe some piece should have cultural value rather than monetary.

rijksmuseum only reason for existing is taks payers money.