A collection of 21 museum-quality automata will be sold at Sotheby’s Important Watches auction in New York on June 11th. The exquisite collection was assembled over 50 years and include late-18th and early-19th century Swiss snuffboxes, music boxes, watches and clocks by the premier craftsmen of the era and later owned by some of the premier collectors, including King Farouk of Egypt. The collection hasn’t been seen since the late 1970s. The crème de la crème of Swiss watchmakers — gold casemaker Jean George Rémond, Piguet & Meylan, Guidon, Guide et Blondel and my personal favorite, Jacquet-Droz — are represented in this elite group.

A collection of 21 museum-quality automata will be sold at Sotheby’s Important Watches auction in New York on June 11th. The exquisite collection was assembled over 50 years and include late-18th and early-19th century Swiss snuffboxes, music boxes, watches and clocks by the premier craftsmen of the era and later owned by some of the premier collectors, including King Farouk of Egypt. The collection hasn’t been seen since the late 1970s. The crème de la crème of Swiss watchmakers — gold casemaker Jean George Rémond, Piguet & Meylan, Guidon, Guide et Blondel and my personal favorite, Jacquet-Droz — are represented in this elite group.

Pierre Jacquet-Droz, his sons Henri-Louis and Jean-Frédéric Leschot, Pierre’s apprentice who he adopted as a youth, together created three of the most advanced automata of the age. Built between 1768 and 1774, The Writer, The Draughtsman and The Musician toured the royal courts of Europe amazing the aristocracy with their human-like characteristics (The Musician breathes, The Draughtsman blows pencil shards off the paper, The Writer’s eyes follows his quill) and abilities (the Musician’s hands actually play the keyboard instead of moving to a canned tune, the Draughtsman can draw four different designs including portraits of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, the Writer dips his quill in the inkwell, shakes off the excess then writes on a paper that moves). The Writer is the most complex with more than 4,000 components all inside of the figure which, unlike his brother’s and sister’s mechanisms, can be programmed to write anything 40 letters long.

Pierre Jacquet-Droz, his sons Henri-Louis and Jean-Frédéric Leschot, Pierre’s apprentice who he adopted as a youth, together created three of the most advanced automata of the age. Built between 1768 and 1774, The Writer, The Draughtsman and The Musician toured the royal courts of Europe amazing the aristocracy with their human-like characteristics (The Musician breathes, The Draughtsman blows pencil shards off the paper, The Writer’s eyes follows his quill) and abilities (the Musician’s hands actually play the keyboard instead of moving to a canned tune, the Draughtsman can draw four different designs including portraits of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, the Writer dips his quill in the inkwell, shakes off the excess then writes on a paper that moves). The Writer is the most complex with more than 4,000 components all inside of the figure which, unlike his brother’s and sister’s mechanisms, can be programmed to write anything 40 letters long.

The following video show The Writer in action and explains how the mechanism works. It’s still impressive as hell; you can image how stunned 18th century courtiers were.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/bY_wfKVjuJM&w=430]

The three Jacquet-Droz automata are now the pride and joy of the Neuchâtel Museum of Art and History in Neuchâtel, western Switzerland, which has owned them since 1906 when they were purchased by the Neuchâtel Society of History and Archaeology for 75,000 gold francs and donated to the museum. The automata are played for visitors on the first Sunday of every month.

As wonderous as they were, the automata were really just hype men, advertising for the brilliance of Jacquet-Droz clocks which, unlike the one-of-a-kind demonstration pieces, were actually for sale. In 1775, Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz moved to London and a few years later got into business with James Cox, a goldsmith, inventor and entrepreneur who also made fantastical automata, most famously The Peacock Clock, now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg and the only surviving multi-figure automaton from the 18th century to survive with all its original parts in working condition.

Cox had been producing gold clocks, music boxes and other mechanical devices for trade with the Far East, first India and then China, since the mid-1760s. The Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1736–95) was an avid clock collector and Cox’s pieces were in high demand for years. After some business setbacks (import bans, the American Revolution’s interference with British trade, bankruptcy), Cox got back in the saddle thanks to his deal with Jaquet Droz. From then on almost all of his exports to China were the Swiss watchmaker’s pieces and most of Jaquet Droz’s production went to China. The masterpieces by other watchmakers in the upcoming sale were also made for the Chinese market.

Cox had been producing gold clocks, music boxes and other mechanical devices for trade with the Far East, first India and then China, since the mid-1760s. The Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1736–95) was an avid clock collector and Cox’s pieces were in high demand for years. After some business setbacks (import bans, the American Revolution’s interference with British trade, bankruptcy), Cox got back in the saddle thanks to his deal with Jaquet Droz. From then on almost all of his exports to China were the Swiss watchmaker’s pieces and most of Jaquet Droz’s production went to China. The masterpieces by other watchmakers in the upcoming sale were also made for the Chinese market.

These were small, elegant objects — gold and enameled pocket watches, snuffboxes, music boxes — with moving elements and chimes. They were expensive and hard to make, and like all luxury items worthy of the name, only a small number of them were produced. There are a few hundred Jaquet-Droz pieces still in existence, and most of them are in museums. On the rare occasions that they appear on the market, they sell for high seven figures at least, often crossing over into the million dollar range.

The biggest star of the upcoming sale is a Jaquet-Droz Singing Bird Scent Flask timepiece from around 1785-90. The shape of a perfume flask, it is 16 centimeters (a hair over six inches) high and is made of gold with enamel and jeweled decorations on a field of deep blue guilloche enamel. Inside is a tiny articulated ivory bird less than half an inch high that moves its wee beak and tail while a miniature organ plays his song which sounds like a real birdsong, not some tinny chimes. It is so delicate, so precious and has traveled so many long distances in its life, it’s nigh on unbelievable that it still works. It sounds great, too.

The biggest star of the upcoming sale is a Jaquet-Droz Singing Bird Scent Flask timepiece from around 1785-90. The shape of a perfume flask, it is 16 centimeters (a hair over six inches) high and is made of gold with enamel and jeweled decorations on a field of deep blue guilloche enamel. Inside is a tiny articulated ivory bird less than half an inch high that moves its wee beak and tail while a miniature organ plays his song which sounds like a real birdsong, not some tinny chimes. It is so delicate, so precious and has traveled so many long distances in its life, it’s nigh on unbelievable that it still works. It sounds great, too.

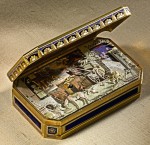

You can see its movement and hear its sound in this video by Sotheby’s which also shows two other glorious pieces in action: The Marriage, a gold two-tune musical automaton snuffbox with an enamel scene of a wedding in classical antiquity on the lid and inside a mechanical workshop where men sharpen and use their tools, also by Jaquet-Droz, and The Fortune Teller, a gold snuffbox with an enamel painting of a fortune teller telling fortunes on the lid and inside a musical automaton of a lady playing the harp and a gentleman playing the lute against a beautifully painted classical interior, made by Piguet & Meylan, case by Jean-George Rémond.

You can see its movement and hear its sound in this video by Sotheby’s which also shows two other glorious pieces in action: The Marriage, a gold two-tune musical automaton snuffbox with an enamel scene of a wedding in classical antiquity on the lid and inside a mechanical workshop where men sharpen and use their tools, also by Jaquet-Droz, and The Fortune Teller, a gold snuffbox with an enamel painting of a fortune teller telling fortunes on the lid and inside a musical automaton of a lady playing the harp and a gentleman playing the lute against a beautifully painted classical interior, made by Piguet & Meylan, case by Jean-George Rémond.

Wow! Amazing. Thank you for posting this.

Thank you for being as wowed with the automata as I am.

Wow, and thanks! The Peacock Clock is beyond amazing!

It really is. I can’t believe it surivived the Revolution unscathed.

Truly amazing. Another wonderful post here at thehistoryblog.com.

I’m puzzled as to why others didn’t grab hold of what Droz was creating in the mid-1770s and see any application for industrial use.

Am I mistaken or did this kind of work just fall out of favor until much later? The inner workings of The Writer as shown in the BBC piece seem to pre-date what Alan Turing created to break the German code during WWII (at least as was shown in The Imitation Game)

Charles Babbage is probably the next link in the chain connect the watchmakers’ automata to Turing’s work and modern computing. There are significant similarities between the mechanism that powers The Writer and Babbage’s difference engine, and Babbage started working on it in the 1820s, just a few decades after The Writer was made. Some of the automata in this sale date to the first decade of the 19th century, so the early dawn of the computer came right on the heels of these mechanisms.

Of course, Babbage. I completely skipped his work before Turing.

Wouldn’t it be something to find writings, musings, sketches and such that would draw a line from Droz to Babbage to Turing (and other thinkers whose names and work I don’t know).

In a game I used to play one of my favorite villains was also known as the Prussian Prince of Automatons. Official details are a bit sketchy because at more than 100 years old he may or may not be a brain in a giant automaton body. One set of missions had me as the plucky hero chasing after him as he uncovered the secrets of immortality after kidnapping one known immortal guy, some scientific vampires and body part replacement theorists. One of the best art assets in the game was actually never used: The Nemesis Warhorse

http://i.imgur.com/Ho4zM4l.jpg

Many thanks to you Marcus Livius Drusus for sharing with your loyal readers such mind bending creations that have fallen from the minds and hands of mortal men.

I know every Senator of the Roman Republic shares my sense of indebtedness to you for the never ending wonderful stories you share on The History Blog.

The Writer Automaton caused me to break out in a great smile to contemplate that such an idea could spring from the marvelous mind of Master Watchmaker Jacquet-Droz.

Thank you and thank you encore.

dp