Thanks to the efforts of George Takei, his legion of fans and thousands of people around the round, a collection of 450 artifacts from Japanese American internment camps have been saved from the auction block and acquired by the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles. The collection had been consigned to the Rago Arts and Auction Center in Lambertville, New Jersey, for sale on April 17th, but on April 9th Japanese Americans and heritage organizations including the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation came together to start a Facebook page and Change.org petition protesting the auction.

Thanks to the efforts of George Takei, his legion of fans and thousands of people around the round, a collection of 450 artifacts from Japanese American internment camps have been saved from the auction block and acquired by the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles. The collection had been consigned to the Rago Arts and Auction Center in Lambertville, New Jersey, for sale on April 17th, but on April 9th Japanese Americans and heritage organizations including the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation came together to start a Facebook page and Change.org petition protesting the auction.

The Japanese American History: NOT for Sale campaign quickly garnered thousands of supporters, among them actor and activist George Takei. Takei, long before he became famous for playing Star Trek‘s Hikaru Sulu, spent three years of his childhood imprisoned in internment camps with his family — first the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, and then the Tule Lake War Relocation Center in California. He now serves as chairman emeritus on the JANM’s Board of Trustees. He publicized the efforts to halt the sale and contacted David Rago to work on a solution that would spare the artifacts of Japanese American internment from being dispersed to the highest bidders. Takei negotiated on behalf of the Japanese American National Museum and personally wrote a check to ensure the collection was kept together in the public interest.

The Japanese American History: NOT for Sale campaign quickly garnered thousands of supporters, among them actor and activist George Takei. Takei, long before he became famous for playing Star Trek‘s Hikaru Sulu, spent three years of his childhood imprisoned in internment camps with his family — first the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas, and then the Tule Lake War Relocation Center in California. He now serves as chairman emeritus on the JANM’s Board of Trustees. He publicized the efforts to halt the sale and contacted David Rago to work on a solution that would spare the artifacts of Japanese American internment from being dispersed to the highest bidders. Takei negotiated on behalf of the Japanese American National Museum and personally wrote a check to ensure the collection was kept together in the public interest.

On April 15th, Rago announced the lots were being removed from sale. On May 2nd, at a gala event where Takei was given the museum’s Distinguished Medal of Honor For Lifetime Achievement, JANM announced that they had acquired the collection for an undisclosed sum.

“Taking the auction off the calendar was a great victory for the Japanese American community and its friends,” said Sacramento resident Yoshinori “Toso” Himel, an organizer of the “NOT for Sale” campaign. “A second victory was the announcement that now the items will be in a community institution.”

When Himel and his wife, Japanese American historian Barbara Takei (no relation to George Takei), saw an unlabeled photo of Himel’s mother earlier this year in one of the 23 lots up for auction, the couple joined forces with other Sacramento Japanese Americans, including the Florin Japanese American Citizens League, to oppose the public sale. […]

Himel, also the founding president of the Asian/Pacific Bar Association of California, said the artifacts need to be interpreted and placed in their proper context. He said his mother’s photo, which shows her smiling while her eyes are downcast, was used as propaganda by the War Relocation Authority “to mask the tragedy suffered by her and an entire racial group of innocent people.”

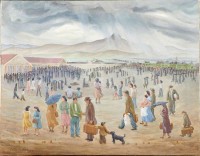

The collection was first amassed by folk art expert Allen H. Eaton. Eaton had wanted to document the art produced by the internees as early as 1943 and in 1945 he visited five of the camps in person. He also dispatched colleagues to photograph the works made at four other camps. During his travels through the camps, he collected a unique group of artworks, furniture, photographs and other items, most of them gifts from the internees at Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming. In 1952, his seminal book Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps, introduction by Eleanor Roosevelt, was published. In it Eaton wrote: “This evacuation, regardless of its military justification, was not only, as is now generally acknowledged, a great wartime mistake, but it was the most complete betrayal, in one act, of civil liberties and democratic traditions in our history, and a clear violation of the constitutional rights of seventy thousand citizens.”

The collection was first amassed by folk art expert Allen H. Eaton. Eaton had wanted to document the art produced by the internees as early as 1943 and in 1945 he visited five of the camps in person. He also dispatched colleagues to photograph the works made at four other camps. During his travels through the camps, he collected a unique group of artworks, furniture, photographs and other items, most of them gifts from the internees at Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming. In 1952, his seminal book Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps, introduction by Eleanor Roosevelt, was published. In it Eaton wrote: “This evacuation, regardless of its military justification, was not only, as is now generally acknowledged, a great wartime mistake, but it was the most complete betrayal, in one act, of civil liberties and democratic traditions in our history, and a clear violation of the constitutional rights of seventy thousand citizens.”

Eaton originally intended to put the artifacts he had received on display in an exhibition that would do justice to the 120,000 Japanese Americans, 60,000 of them children, interned during the war. The internees who gave him their artworks and personal belongings did so with the understanding that they would speak for them in this exhibition, but it never happened.

Eaton originally intended to put the artifacts he had received on display in an exhibition that would do justice to the 120,000 Japanese Americans, 60,000 of them children, interned during the war. The internees who gave him their artworks and personal belongings did so with the understanding that they would speak for them in this exhibition, but it never happened.

Ten years later Eaton died and his collection went to his heirs who later passed it on to Thomas Ryan, a contractor who worked for the Eatons and was also a family friend. Thomas Ryan bequeathed it to his son John, a Connecticut credit-card marketing executive. Ryan felt he wasn’t in a financial position to give away the artifacts which Rago had valued at $27,000 but he hoped museums and internment camp organizations would successfully bid for the lots. As large groups of internment artifacts don’t come up for sale often, the auction would have established commercial value benchmarks, a notion that itself was deeply offensive to the Japanese American community, as was the idea of pitting private collectors against non-profit organizations and the families of internees whose likenesses, names and artworks were being sold.

Ten years later Eaton died and his collection went to his heirs who later passed it on to Thomas Ryan, a contractor who worked for the Eatons and was also a family friend. Thomas Ryan bequeathed it to his son John, a Connecticut credit-card marketing executive. Ryan felt he wasn’t in a financial position to give away the artifacts which Rago had valued at $27,000 but he hoped museums and internment camp organizations would successfully bid for the lots. As large groups of internment artifacts don’t come up for sale often, the auction would have established commercial value benchmarks, a notion that itself was deeply offensive to the Japanese American community, as was the idea of pitting private collectors against non-profit organizations and the families of internees whose likenesses, names and artworks were being sold.

“I believe that through understanding comes respect, and JANM continues to take major steps forward to increase the public’s understanding of a grievous chapter in American history,” said Takei, chairman emeritus of the museum’s Board of Trustees, and the fifth recipient of JANM’s Medal of Honor. “All of us can take to heart that our voices were heard and that these items will be preserved and the people who created them during a very dark period in our history will be honored. The collection will now reside at the preeminent American museum that tells the story of the Japanese American experience.”

Can George Takei get any more awesome?

Just when I think he’s reached maximum awesome, he gets even awesomer.

My name is Eric Moog. During World War II my grandfather was in the cavalry. He was transferred to manzanar internment camp in California. My mother was a child and befriended a very kind man and woman that were there. That didn’t make my grandfather happy. Very sad. This man and woman had put together a small dollhouse for my mother using their own linen and hair. The man had built this little dollhouse that the dolls set in. I’m trying to find out more about this and if any more of these doll houses were made?

Seriously, that guy is awesome.

God yes.

There was a good article in this morning’s New York Times about former internees returning to the Amache camp in Colorado. After 70 years most of the people who make the annual trek were children in the camps.

Indeed, Takei was just five years old when he was interned. He’s 78 now.

I’ve met George twice, hard to find a warmer human being.

So lucky! I assume you haven’t washed your hands since.

I thought it read saves the internet.

That too. Many times over.

I am the same age as George Takai, and grew up just across the OR/CA border from the camps. I never knew about them, but heard talk as I was growing up. Learning what happened stunned me. My parents were embarrassed about it, but I wondered why they hadn’t questioned it when it happened. The original intent behind the collection was honorable, and I am glad that it is coming to fruition, though sad that it happened the way it did. I doubt I’ll ever get to LA to see the show but I sure am going to try to find a copy of that book so I can see it.

That is fascinating that you were never told of the camps when you grew up so close to them. I wonder if your parents feared a Japanese invasion during the war.