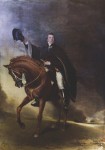

The cloak worn by the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo is being offered for sale for the first time in 200 years. Wellington was a practical fellow when it came to his wardrobe, as evinced by his invention of that most sensible of boots. He eschewed the showy military outfits that were popular in his day (shout out to Joachim Murat), and this simple navy blue worsted cloak with purple velvet collar and plain gilt buttons is a fine example of his utilitarian style.

The cloak worn by the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo is being offered for sale for the first time in 200 years. Wellington was a practical fellow when it came to his wardrobe, as evinced by his invention of that most sensible of boots. He eschewed the showy military outfits that were popular in his day (shout out to Joachim Murat), and this simple navy blue worsted cloak with purple velvet collar and plain gilt buttons is a fine example of his utilitarian style.

It also has a splendidly juicy ownership history. Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, was a highly accomplished swordsman in more ways than one. He cut a swath through the fine ladies, married or not, and courtesans of Regency England, and his conquests in the bedroom figured prominently in society gossip, courtesan memoirs (the famous phrase “Publish and be damned” was his response to the publisher of Harriette Wilson’s memoirs when they offered to keep the Duke’s name out of her scandalous book for a fee), satirical cartoons and divorce court documents. Count Molé, who met Wellington after Waterloo, described him as having “a taste for women, continual amours of extreme ardour and equally extreme frivolity, all the habits of a man of the world and a thirst for the pettiest amusements.”

After Napoleon’s final defeat, abdication and exile, Wellington went to France where he enjoyed an active social life in the packed salons, ballrooms and theaters of Bourbon Restoration Paris. As the greatest military hero on the winning side, Wellington had his pick of the noble groupies that flocked to him. One of them was Lady Caroline Lamb who was then two years out of her scandalous affair with Lord Byron and its even more scandalous aftermath in which she stalked him with violently unhinged dedication.

She and her poor, benighted husband William Lamb, went to Paris in August of 1815 for some R&R after she had spent a month helping nurse her brother Frederic back to health. Colonel Frederic Ponsonby, commander of the 12th Light Dragoons, was a great favorite of Wellington’s who had been so seriously wounded at Waterloo that it’s hard to believe he survived. Leading a cavalry charge, he was shot in both arms. Then he took a sabre blow to the head which knocked him unconscious and off his horse. When he came to, he raised his head only to be spotted by a French lancer who stabbed him with said lance in the back, puncturing a lung. Unable to move, he was roughly searched for plunder at least three times by soldiers on both sides and was unintentionally trampled by Prussian cavalry.

She and her poor, benighted husband William Lamb, went to Paris in August of 1815 for some R&R after she had spent a month helping nurse her brother Frederic back to health. Colonel Frederic Ponsonby, commander of the 12th Light Dragoons, was a great favorite of Wellington’s who had been so seriously wounded at Waterloo that it’s hard to believe he survived. Leading a cavalry charge, he was shot in both arms. Then he took a sabre blow to the head which knocked him unconscious and off his horse. When he came to, he raised his head only to be spotted by a French lancer who stabbed him with said lance in the back, puncturing a lung. Unable to move, he was roughly searched for plunder at least three times by soldiers on both sides and was unintentionally trampled by Prussian cavalry.

Finally, after languishing 18 hours on the field, the morning of June 19th Ponsonby was rescued and carted to nearby farmhouse where his wounds were tended to. Sort of. Here’s his description of his medical treatment as told to Wellington’s great friend (and lover, of course) Lady Frances Shelley: “I had received seven wounds; a surgeon slept in my room, and I was saved by continual bleeding — 120 ounces in two days, besides a great loss of blood on the field.” So yeah, first he survived getting shot, stabbed and trampled at Waterloo, and then he survived his surgeon tapping his veins like a keg.

Wellington visited Ponsonby on June 20th, missing Lady Caroline and William who arrived in Brussels in early July and stayed with Frederick until he was well enough to go back home. When they moved on Paris, Caroline was ready to party. English novelist Frances Burney, aka Madame d’Arblay, described Caroline in her diary after seeing her in Paris:

“I just missed meeting the famous Lady Caroline Lamb who had been there at [Madame de la Tour du Pin’s] dinner, and whom I saw, however, crossing the Place Royale, from Mme de la Tour du Pin’s to the Grand Hotel ; dressed or rather not dressed, so as to excite universal attention and authorise every boldness of staring from the general to the lowest solider among the military groups then constantly parading the Place — for she had one shoulder, half her back and all her throat and neck displayed as if the call of some statuary for modelling a heathen goddess.”

Lady Caroline’s first cousin, Lady Harriet Granville, daughter of the 5th Duke of Devonshire and the famously unconventional Duchess Georgiana, was also in Paris at that time. She wrote in her diary:

Lady Caroline’s first cousin, Lady Harriet Granville, daughter of the 5th Duke of Devonshire and the famously unconventional Duchess Georgiana, was also in Paris at that time. She wrote in her diary:

“Nothing is more agissant [agitating] but Lady Caroline William Lamb in a purple riding habit, tormenting everybody, but I am convinced she is ready primed for an attack upon the Duke of Wellington and I have no doubt but that she will to a certain extent succeed, as no dose of flattery is too strong for him to swallow or her to administer. Poor William Lamb hides in a small room while she assembles lovers and tradespeople in another. He looks worn to the bone. The D of W talked a great deal about Caroline William. I see she amuses him to the greatest degree especially her accidents which is the charitable term he gives to all her sorties.”

There are no extant letters that conclusively show the Duke of Wellington and Lady Caroline Lamb had an affair, but they were into each other for it to be noticed in public. American writer Washington Irving saw Wellington at a party in Paris paying the men little men as he was “quite engaged by Lady Caroline Lamb.” The news of their mutual interest soon grapevined its way back to London where Harriette Wilson, in a letter to her lover Richard William Meyler, wrote this finely crafted double-burn: “My old beau Wellington … has made I understand a desperate conquest of Lady Caroline Lamb, but then her ladyship was never very particular.”

It’s during this period that the Duke apparently gave Lady Caroline a cloak he had worn at Waterloo as a memento. The only source we have for this gift is the cloak’s first documented owner: Grosvenor Charles Bedford. He got it in 1823 from anatomist Anthony Carlisle who told him he had been given the cloak by Lady Caroline who received it from the Duke.

It’s during this period that the Duke apparently gave Lady Caroline a cloak he had worn at Waterloo as a memento. The only source we have for this gift is the cloak’s first documented owner: Grosvenor Charles Bedford. He got it in 1823 from anatomist Anthony Carlisle who told him he had been given the cloak by Lady Caroline who received it from the Duke.

From the Sotheby’s lot notes:

The appearance and characteristics of the cloak itself, together with its provenance, leave little doubt that this was a cloak worn by Wellington during the Waterloo campaign, but it remains impossible to be sure whether he wore it on 18 June 1815. It is almost certain that that he took more than one cloak on campaign; at least one other Waterloo campaign cloak candidate once existed in the hands of Wellington’s friend John Wilson Croker, although that cloak has been lost since 1824. Croker tells the story of how Wellington had given him the cloak worn at Waterloo, but that he lent it to Sir Thomas Lawrence when he was commissioned to paint Wellington for Sir Robert Peel …, and when he asked for it back Lawrence admitted that he had given it – with the Duke’s permission – to a lady, whom Croker declines to identify (The Croker Papers: Volume 3 (1888) p.279). In 1853 Croker wrote to Bedford’s niece, then owner of the present cloak, confirming that her cloak was not the one he had once owned and that Caroline Lamb was not the lady to whom his cloak had been given. This is unsurprising since Lamb’s cloak had already passed to Bedford when Croker lent his cloak to Lawrence.

The cloak, still splattered with mud from the battlefield, will be auctioned on July 14th. The presale estimate is £20,000 – 30,000 ($30,840 – 46,260).

Very Appropriate as its the anniversary of The Battle of Waterloo. It will be interesting to see who buys his cloak. Thanks for this interesting post.

I’m a sucker for a theme post. 😉

“He eschewed the showy military outfits that were popular in his day (shout out to Joachim Murat), and this simple navy blue worsted cloak with purple velvet collar and plain gilt buttons is a fine example of his utilitarian style.”

However, I seem to recall reading many years ago, a description of the events surrounding his death on shipboard during a sea battle against the French.

He was said to be brilliantly “lit up” by all his many Medals and Decorations from past conflicts.

Standing on deck at the height of the battle, his shipmates were concerned that his flashy attire would make him an easy target for a French sharp shooter positioned high on a French mast and accordingly beseeched him to alter his dress.

To such advice it is said he answered with immediate refusal, something to the effect:

“I won these Medals amidst the heat and dangers of past battles and I will not remove them now to garner safety in this present conflict”.

Moments later, he was brought down by a fatal bullet fired by a French sharp shooter.

I wonder if anyone recalls these events- or is my memory beginning to fail me as I am far nearer the end than the beginning.

You’re thinking of Admiral Nelson, I suspect. Wellington died sitting in a chair at home at the age of 83.

Right you are Sir- as Always.

Lord Nelson was the personage who refused to hide his Medals in Battle to increase his own margin of safety by not appearing a walking target.

Did anyone ever portray Lord Nelson in film better than Sir Laurence Olivier.

Always enjoy following your Blog, immensely.

Thanks

WKPD:

In September 1805, the then Major-General Wellesley, newly returned from his campaigns in India and not yet particularly well-known to the public, reported to the office of the Secretary for War to request a new assignment. In the waiting room, he met Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, already a legendary figure after his victories at the Nile and Copenhagen, and who was briefly in England after months chasing the French Toulon fleet to the West Indies and back. Some 30 years later, Wellington recalled a conversation that Nelson began with him which Wellesley found “almost all on his side in a style so vain and silly as to surprise and almost disgust me”. Nelson left the room to inquire who the young general was and on his return switched to a very different tone, discussing the war, the state of the colonies and the geopolitical situation as between equals.On this second discussion Wellington recalled, “I don’t know that I ever had a conversation that interested me more”. This was the only time that the two men met; Nelson was killed at his great victory at Trafalgar just seven weeks later.

Most people think Wellington was very tall in comparison to Napoleon but in fact taking measurements from their remaining uniforms and contemporary notes Napoleon was around two inches taller than Wellington who was also very slight in build, barley larger than today’s average 12 to14year old boy( as his uniforms attest to). It was the wickedly humorous British cartoon lampoonists who made Napoleon grossly fat and short while Wellington was always depicted as tall, slim and stately which still has the world thinking of them in terms of their physical caricatures.

And to think that some people think history is boring. The Enquirer could not come close to this.

Easy mistake to make…. :no:

Almost certain it’s not made from Worsted; looks like superfine to me, which is what I’d expect for a cloak of this style. Woollen, not Worsted.