In late 2001, workers doing construction on the site of a former Soviet Army barracks in a northern suburb of Vilnius discovered a mass grave which fragments of military uniforms identified as the final resting place for more than 3,000 soldiers and support staff of Napoleon’s Great Army who died during the horrific retreat from Russia in the winter of 1812. The grave was excavated in two stages in 2002 and the preliminary results of the study of the skeletons were published in February of 2004 (pdf). Thanks to two new studies on the skeletal remains, we now know more about the geographical origin and diet of some of the men and women who died in Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign.

In late 2001, workers doing construction on the site of a former Soviet Army barracks in a northern suburb of Vilnius discovered a mass grave which fragments of military uniforms identified as the final resting place for more than 3,000 soldiers and support staff of Napoleon’s Great Army who died during the horrific retreat from Russia in the winter of 1812. The grave was excavated in two stages in 2002 and the preliminary results of the study of the skeletons were published in February of 2004 (pdf). Thanks to two new studies on the skeletal remains, we now know more about the geographical origin and diet of some of the men and women who died in Napoleon’s disastrous Russian campaign.

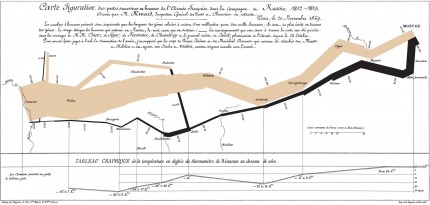

First an infographic. I get emails all the time from people asking me to post their ostensibly history-related infographics and I decline because they tend to be marketing gimmicks that are very light on content. This one is different. Created in 1869 by French civil engineer Charles Joseph Minard, a pioneer of statistics relayed in graphic form, this chart plots the advance of the Great Army into Russia and its devastating retreat. The width of the line marks the size of the army at any given time. The beige line, obese with troops in the beginning, thins out to a quarter of its original size when the army reaches Moscow. The black line then shows the retreating army as it doubles back in the sadly vain attempt to make it out of the Russian winter alive. By the time the black line reaches where the beige line begins, it’s pencil-thin. The 422,000 invasion troops are reduced to 10,000 in retreat, starving, frozen, defeated on an unthinkable scale by a brutal Russian winter and overly extended supply lines.

The deceptively simple chart captures six variables: the size of the army (represented by the thickness of the line), the longitude and latitude of the army (represented by the position of the line), the direction of the army (represented by the two different colored lines), the location of the army on certain dates and, in a line chart underneath the main graphic, the temperature during the retreat. Many cartographers and graphics experts today consider it the greatest information graphic ever made. (Click here for a much larger version translated into English.

The immensity of the disaster that Minard’s graphic conveys so adroitly is exposed on a more human scale by the bones of the fallen. Buttons found in the two trenches of the mass grave identified soldiers and officers from around 30 regiments, most of them infantry, some cavalry, dragoon and foot artillery. There were uniform remains from Italian, Polish and Bavarian regiments as well as the Imperial Guard. There are female skeletons in the mass grave because since 1805 the French army had an official cadre of women working as cooks, laundresses, nurses and sellers of goods like tobacco and alcohol which accompanied the Grand Army in every campaign. Archaeologists were able to determine the sex of 29 female skeletons, but there were probably more women buried with the men as the remains of 1317 individuals were impossible to sex.

The immensity of the disaster that Minard’s graphic conveys so adroitly is exposed on a more human scale by the bones of the fallen. Buttons found in the two trenches of the mass grave identified soldiers and officers from around 30 regiments, most of them infantry, some cavalry, dragoon and foot artillery. There were uniform remains from Italian, Polish and Bavarian regiments as well as the Imperial Guard. There are female skeletons in the mass grave because since 1805 the French army had an official cadre of women working as cooks, laundresses, nurses and sellers of goods like tobacco and alcohol which accompanied the Grand Army in every campaign. Archaeologists were able to determine the sex of 29 female skeletons, but there were probably more women buried with the men as the remains of 1317 individuals were impossible to sex.

The two new studies by University of Central Florida researchers used stable isotope analysis to find out where some of Napoleon’s dead came from and what, if anything, they ate. In one of the studies (pdf), oxygen isotopes in the bones revealed that none of the dead tested were from Vilnius. Of the eight males and one female tested, five of the men were from central and western Europe, three from the Iberian peninsula. The woman was most likely from southern France.

The other study (pdf) took specimens from the bones of 73 men and three women for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis. Carbon isotopes revealed that most of Napoleon’s troops ate wheat in their youth and a few, perhaps from Italy, were raised more on millet. More than a third of the specimens were found to have exceptionally high nitrogen isotope values. While that’s often an indication of a diet high in protein (Richard III, for instance, had a diet rich in game, meat and sea fish and the nitrogen values to prove it), it’s also a reaction to the exact opposite: protein deprivation dramatically raises nitrogen isotope values. Disease can spike nitrogen values as well.

The other study (pdf) took specimens from the bones of 73 men and three women for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis. Carbon isotopes revealed that most of Napoleon’s troops ate wheat in their youth and a few, perhaps from Italy, were raised more on millet. More than a third of the specimens were found to have exceptionally high nitrogen isotope values. While that’s often an indication of a diet high in protein (Richard III, for instance, had a diet rich in game, meat and sea fish and the nitrogen values to prove it), it’s also a reaction to the exact opposite: protein deprivation dramatically raises nitrogen isotope values. Disease can spike nitrogen values as well.

Napoleon’s men were not in good health, even before their ill-fated stop in Vilnius. Research on the teeth of the soldiers in the mass grave showed rampant dental cavities and indications of stress during childhood, and over one-quarter of the dead had likely succumbed to epidemic typhus, a louse-borne disease. A febrile illness like typhus could cause increased loss of body water through urine, sweat, and diarrhea, which may also cause a rise in nitrogen isotopes. And, of course, historical accounts detail how troops fruitlessly scoured the countryside for food and how many of them ate their dead or dying horses.

Consumption of seafood is unlikely to be the cause of the high nitrogen since the frozen Vilnia River wasn’t producing and there were no salted stores to be had. Canning was still in its infancy as French brewer Nicolas Appert had only devised a method to seal food in glass jars in 1809. He did so specifically for the French army, incidentally, after Napoleon offered a 12,000 franc reward to anyone who could solve the military’s thorny supply problems. Glass doesn’t transport well and while a metal can system was invented by Peter Durand in 1810, Durand was British and his patented food preservation products went straight to the Royal Navy, not the Grand Armée.

Consumption of seafood is unlikely to be the cause of the high nitrogen since the frozen Vilnia River wasn’t producing and there were no salted stores to be had. Canning was still in its infancy as French brewer Nicolas Appert had only devised a method to seal food in glass jars in 1809. He did so specifically for the French army, incidentally, after Napoleon offered a 12,000 franc reward to anyone who could solve the military’s thorny supply problems. Glass doesn’t transport well and while a metal can system was invented by Peter Durand in 1810, Durand was British and his patented food preservation products went straight to the Royal Navy, not the Grand Armée.

The culprit is almost certainly prolonged nutritional stress.

The Minard graphic is considered one of the best statistical graphics ever created (possibly the greatest). One of my engineers had a large poster version on the wall of his office!

There are facts that the, otherwise brilliant, chart does not seem to feature. According to Metternich:

“Napoleon calmed himself down, and in a quiet manner he said the following to me […]: The French have no reason to complain about me; in order to spare them, I sacrificed Poles and Germans. I lost 300.000 men in the Moscow campaign, and among them not even 30.000 French. […] But Sire, I exclaimed, You are about to forget that you are talking to a German.”

Indeed, from the 30.000 in the Bavarian Corps VI alone, only 68 seem to have made it.

—

P.S.: What about those ‘ostensibly history-related infographics, very light on content, that tend to be marketing gimmicks’ ? – Whole Empires tend to rise and fall with infographics that seem to be very light on content, delivery or sometimes both.

The French army probably wouldn’t have done well with the circa 1810 British factory canning methods. The canning companies at first tried to process meat in three-pound tins, which didn’t allow the meat to be heated all the way through in such large containers. Thus meat in the tins the British Other Ranks were issued was often spoiled. And that doesn’t even get into the lead solder problem.

I’m baffled that so many people still admire Napoleon; he was essentially a mass murderer of the youth of much of Western Europe.

And when the going got tough he’d just abandon his men, as in Egypt and in Russia.

That infographic is great!

One question about the find though: Napoleon’s Great Army passed through Vilnius twice, both on the way to Moscow and during the retreat. You can clearly see it in the graphic: “Wilna” is “Vilnius” and at both points in time, thousands of people were dying. How do they know the bodies in this mass grave are from people who died during the retreat? (obviously, the retreating soldiers must have been much more starved than those at the beginning but the Grande Armee was already struggling with supply problems when they had just entered Russia and the retreating Russian groups burned the city’s magazines. And during the retreat, most of the camp followers were left behind during the disastrous crossing of the Berezina so you would expect very few women to make it back to Vilnius, but how many “very few” is really depends on the original numbers)

Oh, and I agree with deadrieme about the assessment of Napoleon. It is rarely much short of hero-worship and I don’t think that is justified. Both the French Revolution and Napoleon defy the standard principle that history is written by the victors…

There seems to be something wrong in the tempF scheduling on the translated chart. The correct figures seem to be: tempreaumur(0) = tempC(0) = tempF(32), thus…

tempreaumur(-10) = tempC(-12.5) = tempF(9.5)

tempreaumur(-20) = tempC(-25.0) = tempF(-13)

tempreaumur(-30) = tempC(-37.5) = tempF(-35.5)

:hattip:

Igor, would these Poles, Italians and Germans have been volunteers? I recall that conscription was employed on Frenchmen.

‘Following the Battle of Austerlitz and the War of the Third Coalition, Napoleon dissolved the Holy Roman Empire, annexed parts of Austria and certain German states to France, and formed the [other] German states into the ‘Confederation of the Rhine’ (Rheinbund). Napoleon was their “protector” [Protecteur de la Confédération du Rhin], but as the Confederation was above all a military alliance, their foreign policy was utterly dominated by France, and the states had to supply France with large numbers of military troops. …’ (cf. ‘French period’).

‘The Charter (Rheinbundsakte in German) was written in the French language, and called the entity États confédérés du Rhin, but used the term ‘Confédération’. […]. The constituents of the Confederation were technically not states, but rulers. By joining the Confederation some had their rank elevated, notably a few who became grand-dukes (Grossherzog), who were regarded as of royal status. The Diet of the Confederation, as well as its College of Kings, was chaired by the former Archbishop of Mayence [Mainz], Imperial Archchancellor and Elector, in his capacity as Prince-Primate (Fürstprimas).’ cf.: worldstatesmen[dot]org/Germany.html#Confederation

“indications of stress during childhood,”

Considering that their childhood would probably been spent during the Revolution, that is not surprising.

I don’t think Napoleon was any worse than other political and military leaders. They all seemed to think that sacrificing the sons of ordinary working class families and farm families, for the national good, was perfectly acceptable.

I knew that Napoleon’s soldiers were not in good health, and were desperately underfed. But if over a quarter of the dead men had succumbed to epidemic typhus, we are talking about more than inadequate clothing (in the snow) and not enough protein.

We are talking 10,000 survivors of an army of 422,000, Hels – check Mindard’s fine chart, so maybe cool it on the “not any worse” front?

It would be interesting how many days’ dead are in the pit.

Something similar in China and Russia with Mao and Stalin.

If you look at the chart closely it is worse than you might think.

Napoleon left Moscow with 100,000 men, presumably 100,000 effectives, on October 18. This was down to 20,000 by the time the detachment from “Poltrk” joined the column on November 23, bringing the total force up to about 50,000, certainly not any place close to that many effectives. By the crossing of the River Berezina on November 27, the force was reduced to 28,000 and 12,000 a week later and to 4,000 an other week later on the approach to the Neimen River crossing where a detachment joined that increased the head count to the 10,00 who crossed out of Russia.

If the total army advancing on Moscow after the departure of the detachment that joined just before the Neimen crossing was 400,000 and the surviving force before that detachment rejoined was 4,000, the odds of any one soldier returning were awfully slim, even slimmer for any one soldier who was with the army when it left Moscow.

If Vilnius is the Wilna from the infographic, then the chart lists it as December 7 with a temperature of -26c. How did these men, ill and exhausted (and probably utterly dispirited) dig this mass grave in the frozen ground?

I also wonder how many of the people living along this route died when all their food, and likely their livestock as well, was appropriated for this doomed army. A very high butcher’s bill indeed for ‘the little general’.

Of course we are baffled by Napoleon! At least he did something…The Congres of Vienna just turned back time 50 years. I’m baffled that people admire those conservative heads of states of those days!