One of the most important private collections of ancient sculpture in the world hasn’t been on display in four decades. In fact, it really hasn’t been on public display since the 19th century. The Torlonia family’s collection of antiquities, 620 world-class Greek, Roman and Etruscan statues and sarcophagi, has been favorably compared without hyperbole to the ancient sculpture collections of the Capitoline and Vatican Museums, and the Italian government has tried for years to craft an agreement with the family that would allow these unique treasures to be seen by the public. On Tuesday, March 15th, Culture Minister Dario Franceschini announced that the long-sought agreement has been reached and about 60-90 of the most important pieces in the Torlonia collection will go on display in 2017. The details haven’t been worked out yet, but the likely venue will be the Palazzo Caffarelli Clementino on the Capitoline Hill.

One of the most important private collections of ancient sculpture in the world hasn’t been on display in four decades. In fact, it really hasn’t been on public display since the 19th century. The Torlonia family’s collection of antiquities, 620 world-class Greek, Roman and Etruscan statues and sarcophagi, has been favorably compared without hyperbole to the ancient sculpture collections of the Capitoline and Vatican Museums, and the Italian government has tried for years to craft an agreement with the family that would allow these unique treasures to be seen by the public. On Tuesday, March 15th, Culture Minister Dario Franceschini announced that the long-sought agreement has been reached and about 60-90 of the most important pieces in the Torlonia collection will go on display in 2017. The details haven’t been worked out yet, but the likely venue will be the Palazzo Caffarelli Clementino on the Capitoline Hill.

The Torlonia family are new, by Roman standards. The founder was Marino Torlonia, born Marin Tourlonias in Auvergne, France, in 1725. He moved to Rome and became the manservant of powerful Neopolitan cardinal Troiano Acquaviva d’Aragona, best remembered today for having employed Giacomo Casanova in 1744 only to dismiss him when he was discovered hiding a teenaged runaway in the cardinal’s residence on the Piazza di Spagna. Acquaviva died in 1747, leaving Marino Torlonia an inheritance which he used to set himself up as a textile merchant.

The business was successful and Marino parlayed some of his income into a small lending concern. When he helped Pope Pius VI with some pesky financial matters, he was granted the title of duke. It was his son Giovanni Raimondo Torlonia who took both businesses and ran with them. He made savvy deals with the French occupiers under Napoleon and when the French troops left after the Treaty of Paris in 1814, Giovanni was flush with cash, cash the old noble families distinctly lacked. The Banco Marino Torlonia was delighted to loan them money with their estates and furnishings as collateral.

The business was successful and Marino parlayed some of his income into a small lending concern. When he helped Pope Pius VI with some pesky financial matters, he was granted the title of duke. It was his son Giovanni Raimondo Torlonia who took both businesses and ran with them. He made savvy deals with the French occupiers under Napoleon and when the French troops left after the Treaty of Paris in 1814, Giovanni was flush with cash, cash the old noble families distinctly lacked. The Banco Marino Torlonia was delighted to loan them money with their estates and furnishings as collateral.

Pope Pius VII granted Giovanni Raimondo Torlonia a princely title in 1814, the first of many. Just two generations removed from Marin Tourlonias, the Torlonia family was one of the richest in Rome, as ennobled as it could be and, thanks to advantageous marriages, related to some of the greatest noble houses of the city — the Colonna, Orsini and Borghese. When those loans went into default, the Torlonia family accumulated lands and artworks by the cartload, including pieces from the Orisini, Cesarini and Caetani-Ruspoli families and a prized 17th century collection of ancient sculptures from the Giustiniani family.

Not that they needed the loan collateral to make out like bandits. After the upheaval of the Napoleonic period, many noble families were compelled to sell their properties and private collections. The great collection of dedicated antiquarian Cardinal Alessandro Albani was sold along with his Roman palace, Villa Albani, to the Chigi family who in turn sold it to the Torlonia. Giovanni also bought more than a thousands pieces from the estate of sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, among which were important sculptures Cavaceppi had acquired from the collections of the Savelli, Cesi and Pio da Carpi families.

Not that they needed the loan collateral to make out like bandits. After the upheaval of the Napoleonic period, many noble families were compelled to sell their properties and private collections. The great collection of dedicated antiquarian Cardinal Alessandro Albani was sold along with his Roman palace, Villa Albani, to the Chigi family who in turn sold it to the Torlonia. Giovanni also bought more than a thousands pieces from the estate of sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, among which were important sculptures Cavaceppi had acquired from the collections of the Savelli, Cesi and Pio da Carpi families.

Their extensive property holdings proved invaluable sources of ancient statuary as well. Draining swamps and developing lands, the Torlonia unearthed antiquities hand over fist, particularly from the man-made Roman harbour of Portus, the town of Fiumicino where Leonardo da Vinci Airport now stands, and the ancient Etruscan cities of Vulci and Cerveteri

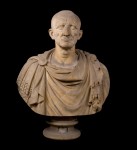

In 1859, Giovanni’s son Alessandro founded a private museum in one of their palaces on the Via della Lungara. The sculptures, including about a hundred Roman portrait busts from the late Republican and Imperial period so prized many scholars consider them superior to the busts in the Capitoline and Vatican Museums, were installed in the 77 rooms of the palace. Already by the 1870s the public was not allowed inside the museum. I can’t confirm whether they ever were, for that matter. Alessandro Torlonia granted access only to his aristocratic friends and occasionally to experts. The collection was catalogued repeatedly in the 1870s and 1880s. Some of the catalogues were illustrated with photographs, among the first in Italy to be printed with pictures instead of drawings. (here’s a text-only example from 1881)

In 1859, Giovanni’s son Alessandro founded a private museum in one of their palaces on the Via della Lungara. The sculptures, including about a hundred Roman portrait busts from the late Republican and Imperial period so prized many scholars consider them superior to the busts in the Capitoline and Vatican Museums, were installed in the 77 rooms of the palace. Already by the 1870s the public was not allowed inside the museum. I can’t confirm whether they ever were, for that matter. Alessandro Torlonia granted access only to his aristocratic friends and occasionally to experts. The collection was catalogued repeatedly in the 1870s and 1880s. Some of the catalogues were illustrated with photographs, among the first in Italy to be printed with pictures instead of drawings. (here’s a text-only example from 1881)

In the 1960s and 1970s, the collection was gradually packed up and stored, perhaps in other Torlonia properties, perhaps in the basement of the old museum. Another Alessandro Torlonia, great-grandson of the museum’s founder, got permission from the government to repair the roof, but those repairs proved to be a smokescreen for an illegal subdivision of the palace into 90 tiny apartments. A 1979 judgement from Italy’s supreme court of appeals found that the sculptures had been stored in “narrow, insufficient, dangerous spaces […] removed from the museum […] crammed together in unbelievable fashion, leaned against each other without care for consistency or history.” The court ruled that the private owner should pay a fine to the state equal to the value lost or diminished by this dire, careless treatment of cultural patrimony. That ruling was never enforced.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the collection was gradually packed up and stored, perhaps in other Torlonia properties, perhaps in the basement of the old museum. Another Alessandro Torlonia, great-grandson of the museum’s founder, got permission from the government to repair the roof, but those repairs proved to be a smokescreen for an illegal subdivision of the palace into 90 tiny apartments. A 1979 judgement from Italy’s supreme court of appeals found that the sculptures had been stored in “narrow, insufficient, dangerous spaces […] removed from the museum […] crammed together in unbelievable fashion, leaned against each other without care for consistency or history.” The court ruled that the private owner should pay a fine to the state equal to the value lost or diminished by this dire, careless treatment of cultural patrimony. That ruling was never enforced.

With tension between the state and the family, the past 40 years have seen many long negotiations go nowhere. Finally the parties have managed to come together, although the vast majority of the Torlonia sculptures will not be on display, at least not right away. I hope this is just a first step. None of these works should be gathering dust in basements.

With tension between the state and the family, the past 40 years have seen many long negotiations go nowhere. Finally the parties have managed to come together, although the vast majority of the Torlonia sculptures will not be on display, at least not right away. I hope this is just a first step. None of these works should be gathering dust in basements.

The history of this collection, how it was amassed from acquisitions, debt collections and excavations on Torlonia properties, may be a central theme of the first exhibition. It’s particularly relevant to the Torlonia collection as opposed to some of the  older ones built gradually by noble families over the course of centuries. The way entire collections were absorbed by the Torlonia makes for a unique perspective into the history of antiquities collection in Rome, with built-in organizational divisions, like, for instance, the pieces from the Cavaceppi collection in one section, the pieces from the Giustiniani collection in another. The sculptures unearthed on Torlonia estates could be in another section.

older ones built gradually by noble families over the course of centuries. The way entire collections were absorbed by the Torlonia makes for a unique perspective into the history of antiquities collection in Rome, with built-in organizational divisions, like, for instance, the pieces from the Cavaceppi collection in one section, the pieces from the Giustiniani collection in another. The sculptures unearthed on Torlonia estates could be in another section.

Again, it’s still in the early stages, but the Ministry is hoping to make this a traveling exhibition. After the Roman show, the treasures of the Torlonia collection will go to top museums in Europe and the United States. Eventually a permanent place will be found for it back home in Rome.

excellent article, teh context very well explained. Thanks

Thank you!

Thanks for the post and – as always – the great context! :hattip:

The story of the Torlonia reminds me of so many families of Rome who arrived from elsewhere and made it big in the Eternal City. As in so many cases, connections to money and power helped to move things along. It’s hard not to stare at the aspects of decadence, though the really interesting stuff goes on behind the spectacle.

For further reading, “The Families Who Made Rome” (by Anthony Majanlahti) provides a fantastic study of these clans who shaped the face and fate of history.

I’ve had that book on my list for years. Time to actually read it. Thank you for the reminder!

Umm… what is that man doing with that sheep?

:giggle: It’s a scene from The Odyssey wherein Odysseus escapes from the giant cyclops Polyphemus he has blinded by tying himself to the belly of his giant sheep. Polyphemus runs his hands over their backs to make sure Odysseus and his men aren’t trying to ride his sheep on out of there, but he neglects to check the undercarriage so the Greeks get away.

Cheryl, remarkably, you did not raise the question what the sheep does to the poor man.

The usual suspect, of course, would be Zeus in even-toed disguise (therefore, confirming your prejudice).

Liv’s explanation, what you possibly knew already, is of course the correct one.

Zeus totally would have, too. He was an equal opportunity horndog. Horneagle? Hornswan? Hornbull? Hornshower-of-gold?

Oh ok, whew!

Very detailed but easy to follow. Good post.

Thank you. 🙂