More than two centuries after they were scattered, a medieval altarpiece, reliquaries and art works from the Premonstratensian convent of Altenberg in central Germany have been reunited at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum. Heaven on Display. The Altenberg Altar and Its Imagery brings together 37 precious devotional objects from the late 13th and early 14th centuries that have been in separate collections since Napoleon was cutting a swath through Europe.

More than two centuries after they were scattered, a medieval altarpiece, reliquaries and art works from the Premonstratensian convent of Altenberg in central Germany have been reunited at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum. Heaven on Display. The Altenberg Altar and Its Imagery brings together 37 precious devotional objects from the late 13th and early 14th centuries that have been in separate collections since Napoleon was cutting a swath through Europe.

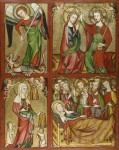

The star of the show is the Early Gothic Altenberg Altar, a folding high altar retable with a shrine cabinet, a polychrome statue of the Madonna and Child in the middle niche and painted panels on each side. The wings, some of the earliest surviving examples of German panel painting, are part the Städel’s permanent collection, but the rest is on loan. Other objects include reliquaries the once were kept in the shrine cabinet of the altarpiece, goldsmithery, 13th century altar crosses, figural glass paintings from an early 14th century window and two embroidered linen altar cloths made around 1330.

The star of the show is the Early Gothic Altenberg Altar, a folding high altar retable with a shrine cabinet, a polychrome statue of the Madonna and Child in the middle niche and painted panels on each side. The wings, some of the earliest surviving examples of German panel painting, are part the Städel’s permanent collection, but the rest is on loan. Other objects include reliquaries the once were kept in the shrine cabinet of the altarpiece, goldsmithery, 13th century altar crosses, figural glass paintings from an early 14th century window and two embroidered linen altar cloths made around 1330.

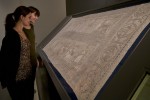

The altar cloths are large, elaborately decorated pieces that were placed on the altar in front of the retable. No other altar cloths from the Early Gothic period in Germany have survived.

The altar cloths are large, elaborately decorated pieces that were placed on the altar in front of the retable. No other altar cloths from the Early Gothic period in Germany have survived.

Sometime before 1192, Emperor Barbarossa granted the convent the status of imperial immediacy, which put it under the direct rule of the Holy Roman Emperor, exempting it from vassalage to the local lords, essentially a guarantee of independence. The daughters of area nobles joined the convent and endowments from their families over time transformed a small, obscure abbey into one of wealth and power.

One of those daughters was Gertrude, the child of St. Elizabeth of Hungary and Louis IV, Landgrave of Thuringia, who died a few months before Gertrude was born. After her beloved husband’s death, Elizabeth dedicated her life to asceticism and charitable works, so much so that she gave up basically everything in the world that she loved, including her children. Little Gertrude was two years old when she was sent to live with the canoness of Aldenberg. She took the veil and became cannoness herself when she was just 21. Her rule lasted until her death 49 years later.

One of those daughters was Gertrude, the child of St. Elizabeth of Hungary and Louis IV, Landgrave of Thuringia, who died a few months before Gertrude was born. After her beloved husband’s death, Elizabeth dedicated her life to asceticism and charitable works, so much so that she gave up basically everything in the world that she loved, including her children. Little Gertrude was two years old when she was sent to live with the canoness of Aldenberg. She took the veil and became cannoness herself when she was just 21. Her rule lasted until her death 49 years later.

Elizabeth was already dead by the time her daughter dedicated her own life to piety and mortification of the flesh, felled by a fever when she was 24 years old. Only five years later she was canonized. Gertrude collected relics of the mother she had only had childhood memories of, if any, for the abbey. The works on display are examples of Gertrude’s devotion to her literally sainted mother. There’s a tapestry from 1270 woven with scenes from the life of Elizabeth and Louis IV which may have been hung behind the altar on important occasions before the altarpiece was built, an arm reliquary shaped like an arm and containing an arm, Elizabeth’s silver jug and a ring that once belonged to Louis.

Elizabeth was already dead by the time her daughter dedicated her own life to piety and mortification of the flesh, felled by a fever when she was 24 years old. Only five years later she was canonized. Gertrude collected relics of the mother she had only had childhood memories of, if any, for the abbey. The works on display are examples of Gertrude’s devotion to her literally sainted mother. There’s a tapestry from 1270 woven with scenes from the life of Elizabeth and Louis IV which may have been hung behind the altar on important occasions before the altarpiece was built, an arm reliquary shaped like an arm and containing an arm, Elizabeth’s silver jug and a ring that once belonged to Louis.

The convent managed to retain its imperial status through the Reformation, the decline of imperial power and rise of the princes after the Thirty Years’ War. It came to an end with the Final Recess of 1803 when Napoleon compensated German princes who had lost lands west of the Rhine to France with ecclesiastical territories. Altenberg, monastery, church and extensive agricultural and forested lands, became the personal property of the Princes of Solms-Braunfels who had long coveted it. They turned the convent into a summer residence and distributed its works of art and devotional objects throughout their castles. The altar went to Braunfels Castle, the arm reliquary of St. Elisabeth to the chapel of Sayn Palace.

The convent managed to retain its imperial status through the Reformation, the decline of imperial power and rise of the princes after the Thirty Years’ War. It came to an end with the Final Recess of 1803 when Napoleon compensated German princes who had lost lands west of the Rhine to France with ecclesiastical territories. Altenberg, monastery, church and extensive agricultural and forested lands, became the personal property of the Princes of Solms-Braunfels who had long coveted it. They turned the convent into a summer residence and distributed its works of art and devotional objects throughout their castles. The altar went to Braunfels Castle, the arm reliquary of St. Elisabeth to the chapel of Sayn Palace.

From there they made their way into museums and collections around the world. The Städel Museum in got the wings of the altar in 1925. Other collections including those of the city of Frankfurt, Munich’s Bayerische Nationalmuseum, the Hermitage in St Petersburg and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City all have bits and pieces of Altenberg. It’s an impressive feat reuniting so many elements of the medieval convent to put the objects in some semblance of their original context.

From there they made their way into museums and collections around the world. The Städel Museum in got the wings of the altar in 1925. Other collections including those of the city of Frankfurt, Munich’s Bayerische Nationalmuseum, the Hermitage in St Petersburg and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City all have bits and pieces of Altenberg. It’s an impressive feat reuniting so many elements of the medieval convent to put the objects in some semblance of their original context.

The exhibition is on right now and runs through September 25th, 2016.

The proper name for an altar frontal is

antependium.

As Heike noted above, these particular examples are not antependia.

Can you get us a straight up photo of the altar cloth?

I’ve added a photo of one of the altar cloths from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. If you’d like to explore the stitching in even more detail, see the additional images on the Met’s website.

http://blogs.artinfo.com/secrethistoryofart/2011/10/24/5-minute-history-of-napoleonic-art-looting/

Napoleon was second only to Hitler in his committment to art theft, and he was far more successful in keeping it. In this case, however, Napoleon was not the looter. It was the German princes who helped themselves to the devotional art once they’d been assigned the territory by treaty and legislation.

ECCE ANCILLA – “Fear not, for thou hast found favour with God. And, behold, thou shalst conceive in thy womb and bring forth a son”, and ECCE COLUMBA, the depictions of the holy spirit as a pigeon, of which on the ‘Isenheimer Altarpiece’ in the left outer wing the bird is shown approaching supersonic speed. :chicken:

Outstanding emoticon use. :notworthy:

The Holy Spirit is depicted as a white dove, the only species with jet speed capability.

FACT.

First it is important to differentiate between an altar cloth and and an antependium. An altar cloth is placed on top of the altar; an antependium in front of the altar. Medieval church regulations stipulated that church altars must be covered by five pieces of linen cloth during church services. (I won’t go into the reasons for this.)

The Altenberg altar cloth also has the distinction of being the only piece of this type of embroidery that was signed by the nuns who stitched it: “Sophia, Hadewigis and Lucardis.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, dates the piece to the second half of the fourteenth century.

It is also not the earliest example of an altar cloth of this type. In my research on Weissstickerei” or counted thread embroidery of the period, the earliest extant altar cloth I could find appears to be an altar cloth from the convent of Isenhagen which dates to around 1300. The earliest surging antependium with this type of embroidery is from the convent of Heiningen and dates to ca. 1250.

Thank you, Heike, for sharing your research. I got the ca. 1330 date of the altar cloths from the Städel Museum, which apparently disagreed with the Met on this matter. I’m not certain if the museum meant that these altar cloths were the earliest surviving in the ebroidery type or in the style of the overall category of design. In your opinion, would the convent of Isenhagen’s altar cloth qualify as Early Gothic?

Hi,

Yes I would say that the altar cloth from Isenhagen is gothic. I went off and did some additional research, and textile expert ? Von Wilckens dates the piece to the second quarter of the fourteenth century. I am hereby changing my opinion of the date.

The full inscription reads: Sophia Haedwigis Lucardis fecert me Ihesu benign E opus nostrum sit ri acceptable.” Roughly translated this reads as “Sophia Haedwigis Lucardis made me may merciful Jesus find favor in our work.”

Source: “Krone und Schleier Kunst aus Mittelalterlichen Frauenkloestern” no publication date given. This work is an exhibition catalog of of medieval and Renaissance conventual art. The English title is The Crown and the Veil”.

The date of the Altar cloth from the Met to c. 1330 stems from the detailed studies carried out by Stefanie Seeberg. Her book on the textiles from Altenberg is extremly interesting – see http://www.medievalhistories.com/medieval-embroidered-textiles-in-whitework/ for a review in English (with links to additional articles of hers in English).

Thank you so much for making me aware of this publication–I can’t wait to buy it.