Vilnius, today the capital of Lithuania, and environs were occupied by the Soviets in 1939 and 1940. The USSR and Germany were allies at the time, and Soviet troops occupied areas of Eastern Europe in concert with Germany’s invasion of Poland. In 1940, the Soviet army began to dig pits for oil storage tanks in the Ponar forest, today known as Paneriai, outside Vilnius to supply a planned airfield. The oil storage project was still in progress in 1941 when Hitler violated the Nonagression Pact and invaded the Soviet Union. The Red Army retreated from Vilnius and the Nazis took over.

Vilnius, today the capital of Lithuania, and environs were occupied by the Soviets in 1939 and 1940. The USSR and Germany were allies at the time, and Soviet troops occupied areas of Eastern Europe in concert with Germany’s invasion of Poland. In 1940, the Soviet army began to dig pits for oil storage tanks in the Ponar forest, today known as Paneriai, outside Vilnius to supply a planned airfield. The oil storage project was still in progress in 1941 when Hitler violated the Nonagression Pact and invaded the Soviet Union. The Red Army retreated from Vilnius and the Nazis took over.

Being as practical as they were murderous, the Nazis thought of another use for the big pits: as execution chambers for tens of thousands of Jews, Poles, Russians, Roma and political prisoners. Between July of 1941 and August of 1944, approximately 100,000 people, 70,000 of them Jews, were forced by SS Einsatzkommando 9 and Lithuanian collaborators to walk down a steep ramp into the pits in the forest. The soldiers standing at the rim of the pit then mowed down everyone inside of them. The victims were buried in the forest.

Being as practical as they were murderous, the Nazis thought of another use for the big pits: as execution chambers for tens of thousands of Jews, Poles, Russians, Roma and political prisoners. Between July of 1941 and August of 1944, approximately 100,000 people, 70,000 of them Jews, were forced by SS Einsatzkommando 9 and Lithuanian collaborators to walk down a steep ramp into the pits in the forest. The soldiers standing at the rim of the pit then mowed down everyone inside of them. The victims were buried in the forest.

As the Red Army advanced in 1943 and it became clear Germany would not be able to hold occupied territories in Eastern Europe for long, the Gestapo ordered that all evidence of genocidal mass-murders be destroyed, in keeping with the Aktion 1005 directive. To accomplish this gruesome goal in Ponar, 80 prisoners from the nearby Stutthof concentration camp were assembled into a “Burning Brigade,” as it became known, and tasked with digging up all the mass graves, cutting wood, piling the corpses onto pyres made from the logs they’d cut, dousing them in gasoline and burning them to ash.

As the Red Army advanced in 1943 and it became clear Germany would not be able to hold occupied territories in Eastern Europe for long, the Gestapo ordered that all evidence of genocidal mass-murders be destroyed, in keeping with the Aktion 1005 directive. To accomplish this gruesome goal in Ponar, 80 prisoners from the nearby Stutthof concentration camp were assembled into a “Burning Brigade,” as it became known, and tasked with digging up all the mass graves, cutting wood, piling the corpses onto pyres made from the logs they’d cut, dousing them in gasoline and burning them to ash.

Guarded by 30 Lithuanian militia and German soldiers and 50 SS men, one guard for each prisoner, the members of the Burning Brigade had to work for three months with their legs shackled together. At night they slept in an execution pit where they knew full well they themselves would be shot to death after their work was done. Eleven of the prisoners had been shot and killed already because of illness of for no particular reason other than sadism or to instill even more terror in the survivors.

Some of the prisoners decided to make an attempt to get out of this hell alive. The lead organizer of the escape attempt was Isaac Dogim, a Jewish man who had recognized his own wife amongst the decaying corpses from a medallion he had given her as a wedding present. His wife, three sisters and three nieces were in the pile of bodies he was forced to burn. With the help of prisoner Yudi Farber, who had been a civil engineer before the war, they dug a tunnel out of the pit with spoons and their own hands as their only tools. Shackled, guarded and using spoons for shovels, the prisoners managed to dig a tunnel 35 meters (115 feet) long over the course of three months.

Some of the prisoners decided to make an attempt to get out of this hell alive. The lead organizer of the escape attempt was Isaac Dogim, a Jewish man who had recognized his own wife amongst the decaying corpses from a medallion he had given her as a wedding present. His wife, three sisters and three nieces were in the pile of bodies he was forced to burn. With the help of prisoner Yudi Farber, who had been a civil engineer before the war, they dug a tunnel out of the pit with spoons and their own hands as their only tools. Shackled, guarded and using spoons for shovels, the prisoners managed to dig a tunnel 35 meters (115 feet) long over the course of three months.

They decided to make a break for it on Passover night, April 14th, 1944. They cut their shackles off with a file and crawled through the tunnel. Forty prisoners made it out of the tunnel, but the guards heard footsteps on branches and began to shoot. Fifteen prisoners made it to the forest. Only 11 eventually reached resistance forces in the Rudniki forest and survived the war. Five days after the escape, the 29 prisoners left at Ponar were shot.

After the war, the Soviets used the Ponar massacre as propaganda, claiming only Soviet prisoners were killed there and denying the overwhelming numbers of Jews and Poles murdered. The survivors of the escape and their descendants kept the real story alive, but the precise location of the tunnel was lost.

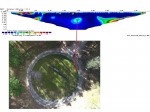

Excavating the site in an attempt to rediscover the tunnel was not possible because it might disturb remains of people murdered by the Nazis, but several attempts were made to locate it with non-invasive means. In 2004, a Lithuanian archaeologist found the entrance to a tunnel inside Pit 6. This year, the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum in Vilnius enlisted a team of researchers from Lithuania, Israel, the United States and Canada to map and explore the tunnel itself without excavation.

Excavating the site in an attempt to rediscover the tunnel was not possible because it might disturb remains of people murdered by the Nazis, but several attempts were made to locate it with non-invasive means. In 2004, a Lithuanian archaeologist found the entrance to a tunnel inside Pit 6. This year, the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum in Vilnius enlisted a team of researchers from Lithuania, Israel, the United States and Canada to map and explore the tunnel itself without excavation.

Led by Richard Freund, a Judaic studies professor at the University of Hartford, and Jon Seligman, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority, the team of historians, archaeologists and geophysicists used ground penetrating radar (GPR) and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), a technology which detects different elements underground from their different levels of electrical resistivity, to scan the entrance to the tunnel. ERT is commonly used by the oil and gas industry as a prospecting device, and by scientists to investigate the water table, fault lines, landslides and more. It can also pinpoint buried archaeological features because their electrical resistivity is different from that of the soil in which they’re buried. On June 8th, the team successfully mapped the entire length of the tunnel and found its exit.

Led by Richard Freund, a Judaic studies professor at the University of Hartford, and Jon Seligman, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority, the team of historians, archaeologists and geophysicists used ground penetrating radar (GPR) and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), a technology which detects different elements underground from their different levels of electrical resistivity, to scan the entrance to the tunnel. ERT is commonly used by the oil and gas industry as a prospecting device, and by scientists to investigate the water table, fault lines, landslides and more. It can also pinpoint buried archaeological features because their electrical resistivity is different from that of the soil in which they’re buried. On June 8th, the team successfully mapped the entire length of the tunnel and found its exit.

The discovery of the tunnel has been filmed for PBS’ always-excellent NOVA series. The episode will cover the history of the Jews in Vilnius, a city with such a rich Jewish culture it was once known as the Jerusalem of Lithuania, the slaughter of 95% of the city’s Jewish population in World War II, and modern archaeological investigations including that of the Ponar tunnel and the excavation of the The Great Synagogue of Vilna. The program is scheduled to air in 2017.

The discovery of the tunnel has been filmed for PBS’ always-excellent NOVA series. The episode will cover the history of the Jews in Vilnius, a city with such a rich Jewish culture it was once known as the Jerusalem of Lithuania, the slaughter of 95% of the city’s Jewish population in World War II, and modern archaeological investigations including that of the Ponar tunnel and the excavation of the The Great Synagogue of Vilna. The program is scheduled to air in 2017.

The research team plans to return to the pit. Working with the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum and the Tolerance Center of Lithuania, the team will open the tunnel to public view as part of a memorial dedicated to the victims of the massacres in Vilnius.

UPDATE: Here is a video of Holocaust survivor Mordechai Zeidel telling the story of the liquidation of the Vilnus (Vilna, then) ghetto, his forced labour in the Burning Brigade and his escape through the tunnel. He was one of the 11 to survive and reach a Jewish partisan group with whom he participated in the liberation of Vilnius. It is subtitled in English.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/5D_qom1YIyA&w=430]

Were Farber and Dogim among the survivors?

They both survived, amazingly enough. Dogim’s oral history was recorded on VHS in 1994 and can be seen on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website. It’s in Hebrew and there are no subtitles, much to my dismay.

Thanks for checking on that! I was hoping they made it through. As for Dogim’s verbal history, it’s really frustrating that there are no subtitles. I’d love to here him describe his escape in his own words.

I’ve just updated the post with video of the recollections of another survivor, Mordechai Zeidel. This one has English subtitles.

*hear

Good post. 👿