John Vanderbank the Elder (his son would become a successful society portrait artist), was born in Paris to a Huguenot family. Religious conflict drove him out of France, first to Holland and then to England where he set up shop as a tapestry weaver. The Vanderbank workshop on Great Queen Street, Covent Garden, was the premier tapestry manufacturer of the late 17th and early 18th century. From 1689 until 1717, he was Yeoman Arras-maker to the Great Wardrobe, meaning he was the official tapestry-maker for the royal family.

John Vanderbank the Elder (his son would become a successful society portrait artist), was born in Paris to a Huguenot family. Religious conflict drove him out of France, first to Holland and then to England where he set up shop as a tapestry weaver. The Vanderbank workshop on Great Queen Street, Covent Garden, was the premier tapestry manufacturer of the late 17th and early 18th century. From 1689 until 1717, he was Yeoman Arras-maker to the Great Wardrobe, meaning he was the official tapestry-maker for the royal family.

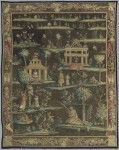

Influenced by Indian textiles, Chinese porcelain and Japanese lacquer, tapestries known as “Indian Manner” were all the rage at the time. India didn’t refer to the subcontinent in any literal sense; this was a mish-mash of vaguely Asian elements, plus Turkish and European themes. Indian Manner tapestries were characterized by multiple colorful scenes set against a dark field, with smaller animal and floral motifs at the top and larger scenes approaching the bottom.

Today Vanderbank tapestries are found in some of Britain’s stateliest homes and in museums like the Victoria & Albert, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Yale University Art Gallery. Because Vanderbank’s workshop was so dominant in English Indian Manner tapestries of his time and because he often reused his more popular designs, making changes in size and placement of motifs based on the wishes of his clients, most tapestries in this style have been attributed to him or his workshop.

Today Vanderbank tapestries are found in some of Britain’s stateliest homes and in museums like the Victoria & Albert, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Yale University Art Gallery. Because Vanderbank’s workshop was so dominant in English Indian Manner tapestries of his time and because he often reused his more popular designs, making changes in size and placement of motifs based on the wishes of his clients, most tapestries in this style have been attributed to him or his workshop.

Then there’s the mysterious Michael Mazarind. There is exactly one known Indian Manner tapestry signed by M. Mazarind, formerly in the collection of Henry McLaren, 2nd Baron Aberconway. Edith Standen noted in her seminal 1981 study (pdf) of Indian Manner tapestries that Mazarind is “a weaver otherwise totally unknown.” She went on to state: “Until more information comes to light about Mazarind (even his name is puzzling), any interpretation of these facts must remain extremely tentative, but he was evidently closely connected with Vanderbank and, like him, was probably not English.”

Despite how very cautiously worded her association of Mazarind with Vanderbank was, it stuck. Enough so that when a buyer recently purchased the tapestry in a private sale, he applied for an export license on the grounds that it did not qualify as a national treasure under the Waverly Criteria because it is not closely connected to Britain’s history, is not of particular aesthetic importance because it’s been altered over time and it is not of outstanding significance for the study of tapestries because there are other Vanderbank tapestries in UK public collections.

The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA) disagreed. In researching the tapestry to determine whether to recommend the granting of an export license, they found that in fact Michael Mazarind was not Vanderbank’s associate, but rather his competitor. He had a workshop of his own, identified from parish rate-books as occupying a space on Portugal Street (now Piccadilly) between 1696 and 1702. The cartoons he used to make the tapestry were not retreads or copies of Vanderbanks, but entirely original.

RCEWA member Christopher Rowell said:

“This beautiful blue ground tapestry, with an equally unusual border of Chinese inspiration, dates from the late 1600s and is the only one to bear the woven signature of the mysterious Michael Mazarind, who was a rival of the more well-known London tapestry weaver, John Vanderbank. This type of ‘Indian’ tapestry depicting a Chinoiserie fantasy paradise in Cathay, with courtly and hunting scenes, was devised for the court, but soon became more broadly popular. Saving the tapestry for the nation will allow specialists to study it in detail and help to reconstruct Mazarind’s contribution to tapestry production in early-Georgian London.”

Following the RCEWA’s recommendation, Culture minister Matt Hancock has placed a temporary export bar on the tapestry. The bar will give British institutions until January 19th, 2017, to raise the £67,500 purchase price. If there is an indication of a serious effort to raise the money that just needs more time, the bar may be extended until April 19th, 2017.

“Yeoman Arras-maker to the Great Wardrobe”: what a title.

Nowadays there would doubtless be a Deputy YAMGW, a Principal Assistant YAMGW, and a Deputy Principal Assistant YAMGW, with the NYT speculating that delayed plans to appoint a person to be DPAYAMGW shows that the Administration is already reeling before it’s even an Administration.

‘Arras’ is also referred to (e.g. in Dutch) as ‘Atrecht’ and already by the Romans as ‘Atrebatum’.

The Belgic Atrebates, themselves, also had a stake in e.g. ‘Calleva Atrebatum’ in what is now England.

Pretty hard to tell, though, if any tapestry was involved for this at all :p

The border is adorable! I like the whole tapestry, but the border is so whimsical and light hearted.