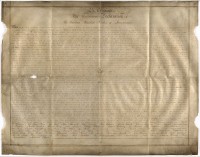

Harvard researchers have discovered a second manuscript written on parchment of the Declaration of Independence in a county archive in Chichester, UK. The only other parchment manuscript is the original Matlack Declaration in the National Archives, the large-scale, or “engrossed,” in the parlance of 1776, version with John Hancock’s John Hancock that everyone pictures when they think of the Declaration of Independence. The newly discovered one is engrossed too, at 24″ x 30″ the same dimensions as the Matlack Declaration, only this one is oriented horizontally instead of vertically.

Harvard researchers have discovered a second manuscript written on parchment of the Declaration of Independence in a county archive in Chichester, UK. The only other parchment manuscript is the original Matlack Declaration in the National Archives, the large-scale, or “engrossed,” in the parlance of 1776, version with John Hancock’s John Hancock that everyone pictures when they think of the Declaration of Independence. The newly discovered one is engrossed too, at 24″ x 30″ the same dimensions as the Matlack Declaration, only this one is oriented horizontally instead of vertically.

In August 2015, Emily Sneff was working on a database of every known example of the Declaration of Independence for Harvard’s Declaration Resources Project when she came across a reference to a copy of the Declaration kept in the West Sussex Record Office. The document was described in the archive’s catalog as “Manuscript copy, on parchment, of the Declaration in Congress of the thirteen United States of America.”

She initially suspected it would turn out to be a printed copy of a kind that were widespread in the 19th century because she had encountered such errors — copies mistakenly catalogued as manuscripts even though they were later prints — in other archives. The reference to parchment, however, was unusual and intriguing. She contacted the West Sussex Record Office and they sent her a CD with photographs of the document.

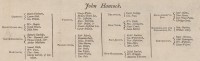

The pictures made it clear that it was indeed a manuscript, not a printed copy, and that wasn’t the only uncommon feature. The names of the signatories were not in their traditional order, with Hancock’s signature first and the rest grouped according to the states they represented in the Second Continental Congress. The punctuation of the text is idiosyncratic and there’s very little of it. There appears to be a spot of erased text at the top, and the neat, compact handwriting was unlike any Sneff had seen before.

The pictures made it clear that it was indeed a manuscript, not a printed copy, and that wasn’t the only uncommon feature. The names of the signatories were not in their traditional order, with Hancock’s signature first and the rest grouped according to the states they represented in the Second Continental Congress. The punctuation of the text is idiosyncratic and there’s very little of it. There appears to be a spot of erased text at the top, and the neat, compact handwriting was unlike any Sneff had seen before.

Sneff took the pictures to her colleague Danielle Allen, and together they worked for two years to unlock its mysteries. They dubbed the manuscript the Sussex Declaration, which is more than a geographical designation. They believe the Sussex Declaration to have belonged to Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, also known as the “Radical Duke” for his avowed anti-colonialist stance and support of American independence. It was likely made in America, probably New York or Philadelphia, and then sent overseas to the Duke, but who commissioned it and whose is the wonderful hand that wrote it remain uncertain.

Sneff took the pictures to her colleague Danielle Allen, and together they worked for two years to unlock its mysteries. They dubbed the manuscript the Sussex Declaration, which is more than a geographical designation. They believe the Sussex Declaration to have belonged to Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, also known as the “Radical Duke” for his avowed anti-colonialist stance and support of American independence. It was likely made in America, probably New York or Philadelphia, and then sent overseas to the Duke, but who commissioned it and whose is the wonderful hand that wrote it remain uncertain.

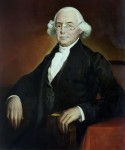

The leading candidate for the commissioner of the parchment is James Wilson of Pennsylvania, himself a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, one of the greatest legal minds of the nascent republic who played a large part in the drafting of the US Constitution and was appointed by President George Washington as one of the first six justices of the Supreme Court. He believed fervently that the principles of the Declaration should play a central role in the political ideology of the United States, despite its not having the strength of law. The Sussex Declaration, notably the arrangement of names, may be making a political statement about the importance of the new country having a strong federal government if it is to succeed.

The leading candidate for the commissioner of the parchment is James Wilson of Pennsylvania, himself a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, one of the greatest legal minds of the nascent republic who played a large part in the drafting of the US Constitution and was appointed by President George Washington as one of the first six justices of the Supreme Court. He believed fervently that the principles of the Declaration should play a central role in the political ideology of the United States, despite its not having the strength of law. The Sussex Declaration, notably the arrangement of names, may be making a political statement about the importance of the new country having a strong federal government if it is to succeed.

Analysis of the parchment, handwriting and spelling date the Sussex Declaration to the 1780s, a period when these issues were front and center in a United States in dire financial straits, fraught with conflict about the role of central government versus the states and still governed by the loose Articles of Confederation.

Among the chief political debates of the era, Allen said, was whether the new nation had been founded on the basis of the people’s authority or the authority of the states. By reordering the names of the signers, perhaps the most conspicuous feature of the parchment, the Sussex Declaration comes down squarely on one side of the argument.

On most documents of the era, Allen said, the protocol was for members of each state delegation to sign together, with signatures typically running either down the page or from left to right, with the names of the states labeling each group. An exception was made for a small number of particularly important documents — including the Declaration, which was signed from right to left, and which omitted the names of the states, though the names were still grouped by state.

“But the Sussex Declaration scrambles the names so they are no longer grouped by state,” Allen said. “It is the only version of the Declaration that does that, with the exception of an engraving from 1836 that derives from it. This is really a symbolic way of saying we are all one people, or ‘one community,’ to quote James Wilson.”

Read about Sneff’s and Allen’s use of handwriting and parchment analysis and their examination of spelling errors in the names of the signatories in their first published paper on the Sussex Declaration (pdf). Their second paper (pdf) focuses on James Wilson, the evidence indicating he commissioned the Sussex Declaration and why. They’re both fascinating, but I was particularly captivated by the second because I knew nothing about James Wilson and he deserved far better from me.

Wow! And it is in excellent condition! What beautiful handwriting, too. My American husband will love this. 🙂

“Harvard researchers have discovered …”: is ‘discovered” the mot juste for someone looking at a Record Office’s records? Can I claim to have “discovered” something in my local university library by pootling in and noticing something obscure on the shelves, or in the computer catalogue?

It reminds me of the old definition of a local historian as someone who unearths things from the county records and reburies them in the university library.

Particularly, I like the bit about the ‘merciless Indian Savages’, and I just have “discovered” that I know a relative of Wilhelm Knyphausen, who fought as auxiliary for the British, as well as I do know a relative of de Kalb, who fought as auxiliary for the ‘Declarists’ in the War of Independence.

Without reasonable doubt, there were Indian auxiliaries as well. Thus, it seems as if there were plenty of ‘foreign and domestic’ officers, as well as there were lots of foreign fighters, who simply had been sold as ‘Mercenaries’ by their nobility. Knyphausen is apparently an exception 😮