The ring fortress discovered on the island of Zealand, Denmark, in 2014 seemed from the first geophysical surveys of the site to fit a very rare and important type of fort built by King Harald Bluetooth (r. 958 — ca. 986). The circular design, the imposing size (475 feet in diameter), the four gates placed at the cardinal compass points, thick inner ramparts encircled by a spiked wooden palisade are all characteristics of Trelleborg-type fortresses, a network of powerful ring forts built by Harald in around 980 A.D. to form a defensive line against Germanic incursions. Only eight Trelleborg-type forts have been found in what is now Denmark and the southern tip of Sweden.

The ring fortress discovered on the island of Zealand, Denmark, in 2014 seemed from the first geophysical surveys of the site to fit a very rare and important type of fort built by King Harald Bluetooth (r. 958 — ca. 986). The circular design, the imposing size (475 feet in diameter), the four gates placed at the cardinal compass points, thick inner ramparts encircled by a spiked wooden palisade are all characteristics of Trelleborg-type fortresses, a network of powerful ring forts built by Harald in around 980 A.D. to form a defensive line against Germanic incursions. Only eight Trelleborg-type forts have been found in what is now Denmark and the southern tip of Sweden.

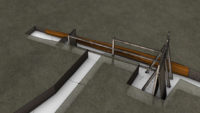

The 2014 excavation was limited in scope. Only a few trenches were dug revealing small sections of what archaeologists believed to be the north and south gates and some of the ramparts. The geophysical data was significant, but open to interpretation. Scholars were reluctant to accept that the Zealand structure, dubbed Borgring, was a fortress of the Trelleborg type based solely on these initial discoveries.

In order to conclusively identify it as one of Harald’s Trelleborg-type forts, archaeologists needed to narrow down the date of its construction as accurately as possible. These forts were built during a short window of a few years at the end of his reign, so pinpointing its age was essential. In the initial excavation, large oak timbers were unearthed at the north gate, charred in a fire that had engulfed the gate after its construction. Preserved by the flames, the wood could be radiocarbon dated, and because the timbers were so large, archaeologists were optimistic that they could be tree-ring dated as well. Carbon-14 testing can only return a date range, but dendrochronological analysis can, in the best case scenario, pinpoint the precise year in which a tree was felled.

In order to conclusively identify it as one of Harald’s Trelleborg-type forts, archaeologists needed to narrow down the date of its construction as accurately as possible. These forts were built during a short window of a few years at the end of his reign, so pinpointing its age was essential. In the initial excavation, large oak timbers were unearthed at the north gate, charred in a fire that had engulfed the gate after its construction. Preserved by the flames, the wood could be radiocarbon dated, and because the timbers were so large, archaeologists were optimistic that they could be tree-ring dated as well. Carbon-14 testing can only return a date range, but dendrochronological analysis can, in the best case scenario, pinpoint the precise year in which a tree was felled.

Two samples taken from the north gate timbers were radiocarbon dated and produced pleasingly consistent dates. The oak logs dated to between 895 and 1017 A.D. Those dates fit squarely within the hoped-for range, but there was still too much wiggle room to prove that Borgring was a Trelleborg fortress. Archaeologists hoped the timbers could be dated dendrochronologically as well, but the charring impeded the analysis.

That was three years ago, and while excavations have been ongoing, the radiocarbon dating results from the north gate timbers have remained the only absolute dates on the table. That changed on June 26th, 2017, when the archaeological team from the Museum of South East Denmark and Aarhus University dug new trenches in the field next to the fortress. Just over eight feet below the surface, the team unearthed a piece of wood about three feet long. The carved oak plank was drilled with holes, some of which contained wooden pegs still in place. There is evidence of wear, but it’s unclear what exactly the plank was used for before it wound up discarded just outside the south gate.

That was three years ago, and while excavations have been ongoing, the radiocarbon dating results from the north gate timbers have remained the only absolute dates on the table. That changed on June 26th, 2017, when the archaeological team from the Museum of South East Denmark and Aarhus University dug new trenches in the field next to the fortress. Just over eight feet below the surface, the team unearthed a piece of wood about three feet long. The carved oak plank was drilled with holes, some of which contained wooden pegs still in place. There is evidence of wear, but it’s unclear what exactly the plank was used for before it wound up discarded just outside the south gate.

Getting discarded was the best thing that could have happened to it, archaeologically speaking, because that field is composed of layer of peat, that blessed substance, preserver of organic remains large and small. The peat kept the wood from rotting and kept its rings in counting order.

Leading specialist in dendrochronological dating, Associate Professor Aoife Daly from the University of Copenhagen and the owner of dendro.dk, has just completed his study of the piece of wood and says: “The plank is oak and the conserved part of the tree trunk has grown in the years 829-950 In the Danish area. A comparison with the material from the Trelleborg fortress in Sjælland shows a high statistical correlation that confirms the dating. Since no splints have been preserved, it means that the tree has fallen at some point after year 966 “.

Research leader Jens Ulriksen says: “The wood piece was found on top of a peat layer, and is fully preserved as it is completely water-logged. We now have a date of wood in the valley of Borgring, which corresponds to the dating from the other ring fortresses from Harold Bluetooth’s reign. With the dendrochronological dating, in conjunction with the traces of wear the piece has, it is likely that the piece ended as waste in the late 900s, possibly in the early 1000’s. ” […]

Søren M. Sindbæk, professor in Archaeology at Aarhus University and part of the excavation team says: “This find is the major break-through, which we have been searching for. We finally have the dating evidence at hand to prove that this is a late tenth century fortress. We lack the exact year, but since the find also shows us where the river flowed in the Viking Age, we also know where to look for more timbers from the fortress.”

The source you quote at the end of your post was a little mixed up. Aoife Daly did not complete “his” study of the piece of wood, but rather her study (http://saxoinstitute.ku.dk/staff/?pure=en/persons/198149). I’m guessing the error may stem from a translation issue, since the verb tenses in her statement are a little jarring as well (the tree trunk “has grown,” the tree “has fallen”).

Alright, our Researcher is female. First, however, the tree “grows” (in the years 829-950), is (likely) ‘harvested’ after 966, and ends up in the ‘borgring’ (in the late 900s or around 980 AD, when the ring is built). Unfortunately, the piece would by waste by the “late 900s” already.

Being myself the ‘timber expert’ that I am, I do suspect here either (a) the ‘borgring’ in question was delivered from IKEA, (b) some form of more or less successful ‘breakthrough’ took place -or- (c) that pegged bit of wood was replaced by a spare part.

——————————–

PS: If there really is a Saxon Institute at ‘Københavns Universitet’, of course, I would not rule out a successful Saxon breakthrough :no: