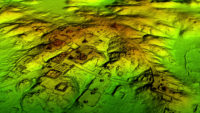

Researchers using LiDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) technology to explore the Maya Biosphere Reserve in the Petén region of Guatemala have found evidence of large public buildings, homes, royal palaces, roads and other structures far more extensive than anyone had any idea existed. More than 60,000 man-made features invisible to the naked eye under the thick jungle canopy have been identified. The scans were done from helicopters. Researchers took aerial shots of the tree tops and then digitally removed the trees, thus peeling back nature’s reclamation of land that the Maya had developed and populated to an astonishingly advanced degree.

The reserve covers an enormous area of 8,341 square miles, almost three times the size of Yellowstone National Park. Within it lie the visible archaeological remains of great Maya cities like Tikal and Holmul. Researchers scanned 10 sections of the reserve totaling more than 800 square miles, a fraction of the Maya Biosphere Reserve but big enough to generate the largest amount of LiDAR data ever collected for an archaeological study.

The reserve covers an enormous area of 8,341 square miles, almost three times the size of Yellowstone National Park. Within it lie the visible archaeological remains of great Maya cities like Tikal and Holmul. Researchers scanned 10 sections of the reserve totaling more than 800 square miles, a fraction of the Maya Biosphere Reserve but big enough to generate the largest amount of LiDAR data ever collected for an archaeological study.

The results suggest that Central America supported an advanced civilization that was, at its peak some 1,200 years ago, more comparable to sophisticated cultures such as ancient Greece or China than to the scattered and sparsely populated city states that ground-based research had long suggested.

In addition to hundreds of previously unknown structures, the LiDAR images show raised highways connecting urban centers and quarries. Complex irrigation and terracing systems supported intensive agriculture capable of feeding masses of workers who dramatically reshaped the landscape.

The ancient Maya never used the wheel or beasts of burden, yet “this was a civilization that was literally moving mountains,” said Marcello Canuto, a Tulane University archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer who participated in the project.

Tulane University archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli, a Maya expert who has made some extraordinary finds on the ground as well as participating in the aerial study, calls the LiDAR data “revolutionary” and expects it will take a century to thoroughly examine and fully understand the sheer masses of information discovered by the scanning technology. The conclusions that can be derived from the material that has been sifted through are exploding what we thought we know about Maya civilization.

Tulane University archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli, a Maya expert who has made some extraordinary finds on the ground as well as participating in the aerial study, calls the LiDAR data “revolutionary” and expects it will take a century to thoroughly examine and fully understand the sheer masses of information discovered by the scanning technology. The conclusions that can be derived from the material that has been sifted through are exploding what we thought we know about Maya civilization.

Already, though, the survey has yielded surprising insights into settlement patterns, inter-urban connectivity, and militarization in the Maya Lowlands. At its peak in the Maya classic period (approximately A.D. 250–900), the civilization covered an area about twice the size of medieval England, but it was far more densely populated.

“Most people had been comfortable with population estimates of around 5 million,” said Estrada-Belli, who directs a multi-disciplinary archaeological project at Holmul, Guatemala. “With this new data it’s no longer unreasonable to think that there were 10 to 15 million people there—including many living in low-lying, swampy areas that many of us had thought uninhabitable.”

Virtually all the Mayan cities were connected by causeways wide enough to suggest that they were heavily trafficked and used for trade and other forms of regional interaction. These highways were elevated to allow easy passage even during rainy seasons. In a part of the world where there is usually too much or too little precipitation, the flow of water was meticulously planned and controlled via canals, dikes, and reservoirs.

Among the most surprising findings was the ubiquity of defensive walls, ramparts, terraces, and fortresses. “Warfare wasn’t only happening toward the end of the civilization,” said Garrison. “It was large-scale and systematic, and it endured over many years.”

This is only the beginning of the project. Over the next three years, the PACUNAM LiDAR Initiative will scan 5,000 square miles of the Guatemalan lowlands, spreading north to the Gulf of Mexico where Maya city states rivalling the ones to the south engaged in some of those centuries of conflict and alliance shifts that necessitated the construction of so many defensive structures.

This is only the beginning of the project. Over the next three years, the PACUNAM LiDAR Initiative will scan 5,000 square miles of the Guatemalan lowlands, spreading north to the Gulf of Mexico where Maya city states rivalling the ones to the south engaged in some of those centuries of conflict and alliance shifts that necessitated the construction of so many defensive structures.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday, February 6th, the National Geographic Channel will premiere a special on the LiDAR research entitled Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake Kings which is a bit of an eye-roller, but there you have it. The Snake Dynasty of Calakmul (which is in Mexico, not Guatemala and so was not scanned in this phase of the project) is undeniably cool, and their influence extended well into the Petén region of modern-day Guatemala, so I get the impulse to put them in the center frame.

So very, very cool. Thank you for sharing! Technology to make us more human, not obsolete is Albert Yu-Min Lin’s philosophy.

I remember a similar story maybe 5 years about about a huge civilization found using technology like this in the Amazon…have they ever dug up any of that, anyone know? are they going to dig here?

Game-changing. Can’t wait to see what other new discoveries this technology will lead us to.

Cannot seem to find a youtube video on how to make my own LiDAR camera…