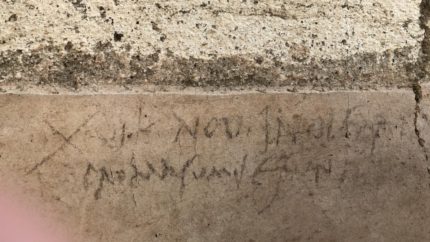

A charcoal date scribbled on the wall of a villa in Pompeii that was undergoing renovations when it was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. is the most precise contemporary evidence yet that the traditional date of the destruction of Pompeii, August 24th, is off by months. The note is dated the 16th day before the Kalends of November (November 1st), which would have been October 17th. There is no year, but the inscription wasn’t meant to be permanent. It was written in charcoal on a white wall that was probably going to be frescoed over as part of a renovation of the home and even if it hadn’t been painted, the charcoal would have quickly faded. That’s why archaeologists are so sure it was left in 79 A.D.

A charcoal date scribbled on the wall of a villa in Pompeii that was undergoing renovations when it was buried by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. is the most precise contemporary evidence yet that the traditional date of the destruction of Pompeii, August 24th, is off by months. The note is dated the 16th day before the Kalends of November (November 1st), which would have been October 17th. There is no year, but the inscription wasn’t meant to be permanent. It was written in charcoal on a white wall that was probably going to be frescoed over as part of a renovation of the home and even if it hadn’t been painted, the charcoal would have quickly faded. That’s why archaeologists are so sure it was left in 79 A.D.

The source of the August date for the eruption is Pliny the Younger. It’s found in a letter written to his friend the historian Tacitus three decades after he witnessed Vesuvius’ fury destroy Pompeii, but the date has been questioned since the early days of Pompeiian archaeology. The discovery of organic remains of autumnal produce like pomegranates, chestnuts, grapes and of heating braziers in homes suggested the city had not been destroyed in the sweltering heat of a southern Italian August. One silver coin also provided strong evidence of a fall date. Minted by the Emperor Titus in 79 A.D., the coin is inscribed with a list of the emperor’s titles one of which notes he was acclaimed imperator 15 times. Titus’ 15th acclamation as emperor took place on September 8th.

So if the eruption took place in October, how to explain Pliny’s letter to Tacitus describing it as having happened in August? He barely escaped a cataclysm that destroyed multiple cities and claimed his uncle’s life. It’s not the sort of thing you’re likely to get so wrong, even 30 years after the event. The answer is transcription errors. Pliny’s original correspondence has not survived, obviously. The text has come down to us in various states of completion from copyists and, like a game of telephone, mistakes get transmitted and even amplified over the centuries. It’s easy to see how scribes might have confused September (the ninth month of the Julian calendar) with November (the ninth month in the ancient Roman 10-month calendar as indicated by the prefix “nov”).

Ancient sources are never as cut and dried as we might wish. There are inconsistencies with the archaeological record and even among the extant manuscripts. The August date comes from the most complete surviving copy of the letter which refers to the “nonum kal. septembres” (nine days before kalends of Septembe), not from all of them. Other copies of Pliny’s letters, including one now in the Girolamini Library in Naples, refer to the kalends of November, three days before the kalends of November and nine days before the kalends (month missing but was probably also November).

Titus only became emperor (imperator) in June 79 – he couldn’t be acclaimed imperator a total of 15 times by September 79, only two months into his reign. Somebody misinterpreted something in the legend engraved on the coin, although I can’t imagine what title on the coin would be numbered as high as 15 in only two months of rule.

Edit: three months into his reign, not two months.

Titus had been a successful general prior to elevation to Emperor, I believe he also acted as a co-ruler to some extent with his father. Based on that I’d suggest he could have been proclaimed several times.

I’m probably wrong 🙂

In the Imperial era, a general’s troops proclaiming him imperator would have been taken as a challenge to the reigning emperor, unlike the way it was used for generals in the Republican era.

The only title I can think of that could numbered so high for any emperor would be consulships, but Titus only had something like seven or eight during his father’s reign, so he sure didn’t have seven or eight more after three months in power himself. I’m curious to see this Titus coin!

Google The Inconvenient Coin: Dating the Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum and you can see pictures of the coin. Great discussion dated June 7, 2013.

Imperial issues of coins minted under Vespasian, 69-79 ad show many “Titus, as Caesar” coins with an imperium (imp) count starting from 71 ad. As time marched by many mintings of the “Titus, as Caesar” coin showed an increase in the imp count. By 79 ad the count was up to imp XIIII when the coins showed “Titus, as Augustus.” Some time in 79 the “Titus as Agustus” minted coins showed imp XV.

“Ancient sources are never as cut and dried as we might wish.” Wise words.

The same is true of family folklore, apparently.

That’s why I love this blog – this is interesting stuff!

There are two versions of this same coin, one with Titus facing right and the other with him facing left. Same coin, same legends, same year. I also read that the one with him facing right was issued from July-September 79, and the version with him facing left was issued from September 79 onward.

The only picture I’ve seen of the coin from Pompeii has Titus facing right – that wouldn’t change the Vesuvius dating. Only a left-facing example would do that.

I got this response from David Atherton, well respected in the ancient coin world:

Titus’ 15th imperial acclamation was awarded for a victory by Agricola in northern Britain (Dio 66.20.3). We can date this issue by a military diploma the British Museum possesses which shows Titus was still IMP XIIII on 8 Sept 79, and he would continue to be COS VII until 31 December 79 (Titus became COS VIII on 1 January 80).

So, sometime between those two dates (8 Sept 79 and 31 December 79) he received his 15th imperial acclamation for the British victory.

Presumably, the victory occurred before the end of the campaign season, perhaps no later than September. It would take a few weeks for news of the battle to reach Rome and the appropriate measures by the Senate to award the acclamation to Titus – early October seems likely. Coins would immediately be struck recording the new title.

Mr. Atherton also left this comment on the “Inconvenient Coin” article, which takes the Pompeii coin out of the eruption conversation:

“Richard Abdy of the British Museum examined the (Pompeii) coin in question last year when it was part of the BM’s Pompeii exhibit. In his article ‘The Last Coin in Pompeii’ in the 2013 Numismatic Chronicle he concluded the reverse legend actually reads TR P VIIII IMP XIIII COS VII, dating it to July/August 79 AD. Oh well.”

———–

Remember, remember the 16th before the calends of November!

———–

Fair enough, ‘XVI K Nov’, the 16th day before the calends of November, or ’17th of October’ in the modern calendar.

But may I humbly ask what the complete inscription does say exactly? – What if they wrote something like “This wall is to be taken down by October 17th”?

“XVI (ante) K(alends) Nov(embres) in[d]ulsit pro masumis esurit[ioni].”

———————————————————————

Il 17 ottobre lui indulse al cibo in modo smodato.

Translation: “On October 17, he over-indulged in food”.

Link to the article: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2018/10/16/new-pompeii-graffiti-may-rewrite-history-in-a-major-way/#22367e954844

On Instagram, Massimo Osanna has provided the full inscription to read:

“XVI (ante) K(alendas) Nov(embres) in[d]ulsit

pro masumis esurit[ioni].”

Translation: “On October 17, he indulged in food immoderately”.

Such cultured language those Roman builders employed in their graffiti 🙂

Thanks …he gave in to hunger (esuritio) over ‘masumis’ (or ‘mesumis’?)

…over the right amount? As my personal Pompeiian Latin skills are certainly ‘below the right amount’, I wonder why and how ‘pro masumis’ is supposed to mean something like ‘excessively’?

Is there a connection to ‘meso-‘? Are we dealing here with ‘Latin from the gutter’ or possibly some kind of urban slang? Maybe to what in Spanish is ‘más’ (more)?

Thus, in other words, would ‘pro masumis’ mean ..’more than more’? :confused:

Many thanks for a very interesting post!

And, for me at least, a joy to find someone who knows and uses the phrase “cut and dried”. (which is everywhere rapidly being supplanted by the utterly inane “cut and dry”.)

yes you are right check this one So if the eruption took place in October, how to explain Pliny’s letter to Tacitus describing it as having happened in August?.