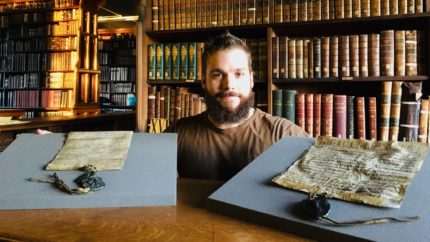

An original royal charter from the reign of King John has been discovered in Durham University’s Ushaw College Library. Dr. Benjamin Pohl, a medieval history professor from the University of Bristol, found the rare document while studying the library’s medieval manuscripts with archivist Dr. Jonathan Bush. As they went through the library’s extensive collection of manuscripts, they discovered a box in the safe with documents that had not been officially catalogued; the royal charter was among them.

An original royal charter from the reign of King John has been discovered in Durham University’s Ushaw College Library. Dr. Benjamin Pohl, a medieval history professor from the University of Bristol, found the rare document while studying the library’s medieval manuscripts with archivist Dr. Jonathan Bush. As they went through the library’s extensive collection of manuscripts, they discovered a box in the safe with documents that had not been officially catalogued; the royal charter was among them.

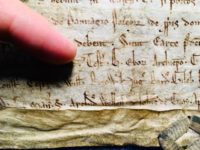

The charter dates to 1200, the first year of King John’s reign and was issued in York on March 26th making it exactly (almost to the day) 819 years old. In it the King confirms the grant of two hamlets — Cornsay and Hedley Hill in County Durham — to Walter of Caen and Robert FitzRoger. FitzRoger was Lord of Warkworth and Sherriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, and both men were the nephews of Simon, a chamberlain of Durham who had received the hamlets more than 15 years earlier as a grant from the Bishop of Durham Hugh de Puiset. Simon wanted to give the hamlets to his nephews but needed the king’s royal charter to make the grants legal and official.

There may have been a undercurrent of political clean-up here too. Hugh de Puiset was thoroughly enmeshed in the turbulent monarchy of Stephen of Blois through the Angevin rulers. He was Stephen’s nephew, either sided against Henry II during his sons’ revolt against him or at least operated shadily in the background against the king. Hugh bought important offices from King Richard for a pretty penny, and when Prince John took control of the throne during Richard’s captivity in Vienna, Hugh opposed him to the point of battle, sending troops against some of John’s properties in the north of England in 1193. Hugh de Puiset died in 1195. John became King of England on May 27th, 1199. Ten months later, John granted Hugh’s nephews the properties his erstwhile enemy had given them.

There may have been a undercurrent of political clean-up here too. Hugh de Puiset was thoroughly enmeshed in the turbulent monarchy of Stephen of Blois through the Angevin rulers. He was Stephen’s nephew, either sided against Henry II during his sons’ revolt against him or at least operated shadily in the background against the king. Hugh bought important offices from King Richard for a pretty penny, and when Prince John took control of the throne during Richard’s captivity in Vienna, Hugh opposed him to the point of battle, sending troops against some of John’s properties in the north of England in 1193. Hugh de Puiset died in 1195. John became King of England on May 27th, 1199. Ten months later, John granted Hugh’s nephews the properties his erstwhile enemy had given them.

Very few original charters from John’s first year of kingship have survived. They are usually known from charter rolls (administrative records of all royal charters) and some contemporary copies that were spread around the country and kept in institutional archives. This royal charter is all the more important because it is only known from the charter roll and there are differences between it and the administrative record. Some are minor differences — spelling mostly — but one is a very notable discrepancy in the list of witnesses. The charter roll only records the Archbishop of York, the Chief Justiciar of England and the Sheriff of Yorkshire and Northumberland as witnesses present at the issue of the charter on March 26th, 1200. The original charter has a much longer list of witnesses, adding the Constable of Chester, the Sheriff of Berkshire, Cornwall and Devon, the Royal Justice and Baron of the Exchequer, the Lord of Kendal, one Germanus Tison and Henry, son of the Archbishop of York, to the ones named in the charter roll.

Dr Pohl said: “Discovering the original charter at Ushaw is extremely exciting, not least because it allows us to develop a fuller picture of the people who were present at York on 26 March 1200 and eager to do business with the new king.

“Medieval charters are important not just because of the legal acts they contain, but also for what they can tell us about the society and political culture at the time. Indeed, their issuing authorities, beneficiaries and witnesses provide a cross section of medieval England’s ruling elites.

“Our charter might best be described, therefore, as a kind of ‘who’s who’ of Northern England (and beyond) at the turn of the thirteenth century.”

And then some. The Durham Residential Research Library collection also includes the original charter in which Hugh de Puiset granted Simon the two hamlets. The discovery of the royal charter allows scholars to compare the two documents side-by-side.

Friends,

So I learned some important things about medieval life from this charter story.

First, this sort of mundane business was why English kings progressed around the realm. It wasn’t all hunting and feasting at somebody else’s expense (though that certainly had its attractions). Kings had to meet their vassals, hear their concerns, settle disputes, and seal stuff (kings didn’t “sign” charters, they affixed their wax seal to them, and that includes the Magna Carta). All this personal contact helped to cement loyalty.

Second, though the most important English documents went to the Tower of London (which housed the royal archives at that time), a lot of lessert documents were stored locally. That is where the charter rolls come in. They were indexes, or if you like, the medieval equivalent of a library card catalog, and gave the off-site locations of many lesser but important records.

Third, making extra copies of charters and spreading their storage locations around helped insure that in case of destruction by natural disaster or war, the information would have a greater chance of survival. When the English invaded Scotland circa 1300 during Edward I’s attempted take-over, he ordered his commanders to suck up all the records they could get their mailed paws on. If they couldn’t send those records to London, the charters and other documents were to be burned. Destroying records was one reason why Edward’s armies trashed the great Scottish monasteries like Jedburg, Kelso and Melrose. This meant that Edward would have full control of land grants and other matters, as lacking their records Scottish nobles would be left with no legitimacy. They would have to start over as Edward’s vassals if the Scots wanted to keep their lands and titles.

The more I study medieval history, the more I see how clever our ancestors were.

Mungo Napier, Laird of Mallard Lodge (SCA)

His disguise must have been really poor, i.e. with all the roasted chickens and gold rings not poor enough.

Duke Leopold, who accused Richard of arranging the murder of his cousin and having cast down his standard from the walls of Acre, kept him luxury prisoner at Dürnstein Castle.

Handed over to Emperor Henry VI, three weeks of captivity at Trifels from 31 March to 19 April 1193 are documented. Richard’s “Ja nus hons pris” (Ja nuls hom pres) was addressed to his half-sister Marie de Champagne.

Note that his Oc version does not seem to mention the parts in France and ‘York’ is seemingly not mentioned at all. In captivity, he wrote the song in French and Occitan, so that I put:

—————

No prisoner’s story can freely be told,

as long as his pain would be totally cold;

Though, he manages to sing this bold.

Many friends I have, but not any support.

It puts them to shame that due ransom,

for now two winters put me in prison.

It’s known to my kin and to my barons,

English, Norman, Poitevin and Gascons,

I don’t have the least of a companion

that would for money remain in prison.

Putting this forward not as allegation,

yet as a prisoner I still linger on.

One thing I as clear to me as is sin,

Once dead I have no friends nor kin,

that wont let me down for silver or gold.

Merely not for me for my dominions,

after my death they will be reproached

that I am held prisoner.

My companions I love and disdain,

the ones from Caen and the Percherain –

Tell them, My Song, they are uncertain,

false or weak hearted never did entertain,

as they now fight me they are villain

As long as I am held prisoner.

Countess sister, your high sovereign(t)

saves and protects from whom I indict

He is blamed that in prison I am kept.

No words I have for those from Chartres,

None to the mother of Louis.

—————

:boogie:

…Check out the song ‘Ja nus hons pris‘ actually sung 😉

Theobald V, Count of Blois [and -if I am not mistaken- nephew of Stephen, King of England?] inherited Blois –including Chartres– and was married to Alix of France (born 1150), and in 1172 Louis I of Blois was born.

Thus, could Alix possibly be “the one from Chartres” that Richard apparently was having no words [of praise, damnation or something else] for? And if so, why would that be? Here, however, a slightly -and hopefully- improved version. Feel free to just fire away, in case you think you have improvement(s) yourself:

—————

No prisoner’s story can freely be told,

as long as his pain would be totally cold;

Though, he manages to sing this bold.

Many friends I have, but not any support.

It puts them to shame that due ransom,

for now two winters puts me in prison.

It’s known to my kin and to my barons,

English, Norman, Poitevin and Gascons,

I dont have the least of a companion

that would for money remain in prison.

Putting this forward not as allegation,

yet as a prisoner I still linger on.

One thing is as clear to me as is sin,

Once dead I have no friends and no kin,

letting me down for a golden or silvery bin.

Not for me, for all my dominion I spin,

after my death the reproach will begin

for I am still held prisoner.

My companions I love and disdain,

the ones from Caen and the Percherain –

Tell them, my song, they are uncertain,

false nor weak hearted I did not entertain,

as they now fight me they are villain

As long as I am held prisoner.

Countess sister, your sovereign fame

protects from whom as guilty I claim

The one I blame that in prison I am.

No words I have for the one from Chartres,

to the mother of Louis.

—————

:hattip:

PS: There might be alternative french verses. The ‘Oc’ version, however, seems to be pretty much identical, only that the bit mentioning “the one from Chartres” is missing (which makes perfect sense to me).

Also, the verse mentioning Caen and the Percherain is a different one (roughly: his heart is sore and it hurts that his [Oc] land is in torments, sacrament without community, still winter and -of couse- still in prison):

————

Nom meravilh s’ieu ay lo cor dolent,

Que mos senher met ma terra en turment;

No li membra del nostre sagrament

Que nos feimes els sans cominalment

Ben sai de ver que gaire longament

Non serai en sai pres.

————

Would –that– make the first one any better? 😉

——

No prisoner’s story can freely be told,

as long as his pain would be totally cold;

Though, he manages to sing this bold.

Many friends I have, but not any support.

It puts them to shame that ransom is short,

for now two winters put me in prison.

——

:hattip:

Richard wrote the song apparently addressing his half-sister Marie de Champagne (Marie of France, Countess of Champagne, ‘Contesse suer’, or as in the occitan version, ‘Suer comtessa’).

Their mother had been Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, which notably was also the mother of Countess Alix, i.e. as indicated seemingly “the [blamable?] one from Chartres”.

Another one of his real sisters was Eleanor of England (‘Alienor filia regis Anglorum’), Queen of Castile, but is is highly questionable if she could be the ‘Suer comtessa’ from the occitan version, which reads:

———–

Ja nuls hom pres non dira sa razon

Adrechament, si com hom dolens non;

Mas per conort deu hom faire canson.

Pro n’ay d’amis, mas paure son li don;

Ancta lur es si, per ma rezenson,

Soi sai dos ivers pres.

Or sapchon ben miei hom e miei baron,

Angles, norman, peitavin e gascon,

Qu’ieu non ay ja si paure companhon

Qu’ieu laissasse, per aver, en preison.

Non ho dic mia per nulla retraison,

Mas anquar soi ie[u] pres.

Car sai eu ben per ver certanament

Qu’hom mort ni pres n’a amic ni parent;

E si’m laissan per aur ni per argent

Mal m’es per mi, mas pieg m’es per ma gent,

Qu’apres ma mort n’auran reprochament

Si sai me laisson pres.

Nom meravilh s’ieu ay lo cor dolent,

Que mos senher met ma terra en turment;

No li membra del nostre sagrament

Que nos feimes els sans cominalment

Ben sai de ver que gaire longament

Non serai en sai pres.

Suer comtessa, vostre pretz soberain

Sal Dieus, e gart la bela qu’ieu am tan

Ni per cui soi ja pres.

———–