When Queen Marie-Antoinette was under house arrest with her family at the Tuileries Palace, she engaged in a secret correspondence with her great friend and former lover Count Hans Axel von Fersen of Sweden. Between June 1791 and June 1792, when the royal family attempted to flee the country in a caper organized by Fersen, they smuggled letters to each other. Those letters remained in the Fersen family long after all parties had been killed. Around 60 letters were published in 1877 by Fersen’s grand-nephew.

France’s National Archives owns 25 of the letters by Marie-Antoinette (four originals written in her hand, the rest copies made by Fersen or his secretary) and 29 letters written by Fersen. Of the 25 letters from the queen, seven of them have redacted passages, adding up to a total of 53 unreadable lines. Of the 29 Fersen letters, 8 of them are redacted, totalling 55 unreadable lines. All of the letters are in good condition.

France’s National Archives owns 25 of the letters by Marie-Antoinette (four originals written in her hand, the rest copies made by Fersen or his secretary) and 29 letters written by Fersen. Of the 25 letters from the queen, seven of them have redacted passages, adding up to a total of 53 unreadable lines. Of the 29 Fersen letters, 8 of them are redacted, totalling 55 unreadable lines. All of the letters are in good condition.

The National Archives has been collaborating with the Center for Research on Conservation (CRC) and the Laboratory of Heritage and Cultural Dynamics (DYPAC) to decipher the redacted text. The censored passages were crossed out with squiggles and because the ink of the letter and the redaction ink are so similar researchers had to find a non-invasive, non-contact technique that could effectively reveal the content. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy was the most effective making it possible for the original text to be read.

The ink is of a type known as metallo-gallic inks, composed of iron sulphate, gall, gum arabic and trade metallic elements that differ from ink to ink. The original ink in the letter contained one element the redaction ink did not contain: copper. That’s what the XFS scanner focused on to reveal the words under the scribbles.

The ink is of a type known as metallo-gallic inks, composed of iron sulphate, gall, gum arabic and trade metallic elements that differ from ink to ink. The original ink in the letter contained one element the redaction ink did not contain: copper. That’s what the XFS scanner focused on to reveal the words under the scribbles.

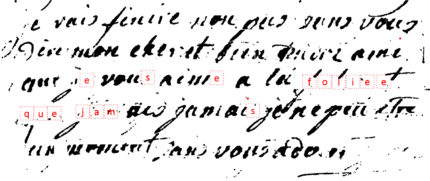

The first letter decoded dates to January 4th, 1792. The redacted portion reads: “I will end [this letter] but not without telling you, my dear and gentle friend, that I love you madly and that there is never a moment in which I do not adore you.”

“For the first time we can read Fersen’s writing using unambiguous sentences on his feelings for the queen, which had been carefully hidden,” said the REX project’s leaders in a statement.

“Marie-Antoinette and Fersen express themselves using the terminology of love, even if the majority of the content of the letters is political,” the statement added.

The second phase of the project will deploy the XRF scanner on the remaining corpus of letters to make the censored passages readable once more. This goal is more challenging because the composition of the underlying and redaction inks are identical. There’s an upside to that, however, because the ink in the redactions of some of the letters is very similar to the ink used by Count Fersen in his letters. This suggests that at least some of the redactions were done by Fersen himself.

Axel was sent to his ‘Grand Tour’ in 1771-75, as it was called back then, where he met Marie-Antoinette in 1774, and later in England met with King George III. Then, in 1779, he joined the French 94th Infantry Regiment, a German regiment in the French army known as the ‘régiment Royal-Bavière’, which from 1780 to 1791 was known as the ‘régiment Royal-Hesse-Darmstadt’ (by the way, not to be confused with those ‘Hessians’ that were leased off to fight on behalf of King George III. of England).

Both “Hessians” were deployed –i.e. on both sides– in the American Revolutionary War, where Axel took part in the ‘Siege of Yorktown’. On meeting Washington, Axel apparently noticed: “He has the air of a hero; he is very cold, speaks little, but is polite and civil. An air of sadness pervades his whole countenance, which is not unbecoming to him, and makes him the more interesting”. However, Fersen arrived back in France in June 1783, where several missions were keeping him busy, some of which might have made it necessary to redact the letters.

I would think someone would be able to come at least very close to figure out what was written just by examining the visible parts of the letters, spacing, word usage at the time etc. without having to resort to spectroscopy.

I am sure they haver already done that, Tristram, but being married to a linguist I well know that there is more to it than that – such as how the letters are formed in the context, the subtleties of the grammatical forms and, most importantly, to see who gets the bragging rights for the most precise estimate :hattip:

Actually after having looked at the pictures more carefully it looks like a lot of the visible apparent letter parts are meaningless additions (ink colors are different) presumably to throw off any person attempting to decipher the lines.

Very interesting! Want to know more…