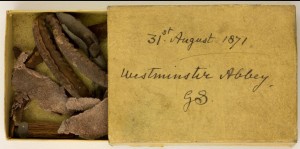

An archivist working on a six-month cataloguing program at the National Portrait Gallery uncovered pieces of wood, leather and fabric from the tomb of King Richard II in a cigarette box marked “August 31, 1871, Westminster Abbey, GS.” The GS stands for Sir George Scharf, the National Portrait Gallery’s first director, who was at Westminster Abbey on August 31, 1871, when Richard II’s tomb was opened for cleaning.

An archivist working on a six-month cataloguing program at the National Portrait Gallery uncovered pieces of wood, leather and fabric from the tomb of King Richard II in a cigarette box marked “August 31, 1871, Westminster Abbey, GS.” The GS stands for Sir George Scharf, the National Portrait Gallery’s first director, who was at Westminster Abbey on August 31, 1871, when Richard II’s tomb was opened for cleaning.

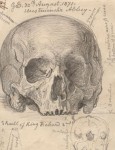

Scharf didn’t just keep souvenirs from Richard’s coffin. He also made thorough sketches of the king’s skull and bones, including detailed measurements. The drawings are so accurate archivists believe it may be possible to reconstruct Richard’s appearance. Chroniclers at the time described him as handsome. He was just 33 when he died on Valentine’s Day, 1400, probably of starvation, while being held in captivity at Pontefract Castle by his usurper cousin, Henry IV.

Scharf didn’t just keep souvenirs from Richard’s coffin. He also made thorough sketches of the king’s skull and bones, including detailed measurements. The drawings are so accurate archivists believe it may be possible to reconstruct Richard’s appearance. Chroniclers at the time described him as handsome. He was just 33 when he died on Valentine’s Day, 1400, probably of starvation, while being held in captivity at Pontefract Castle by his usurper cousin, Henry IV.

The contents of the box were only listed as relics from a royal tomb when catalogued, no specifics about which royal tomb it was. Scharf witnessed the opening of several royal tombs, including those of Edward VI, Henry VII and James I, so archivists had to cross-check the date with diary entries to figure out whose relics they were.

The contents of the box were only listed as relics from a royal tomb when catalogued, no specifics about which royal tomb it was. Scharf witnessed the opening of several royal tombs, including those of Edward VI, Henry VII and James I, so archivists had to cross-check the date with diary entries to figure out whose relics they were.

Krzysztof Adamiec, National Portrait Gallery Assistant Archivist (Scharf Project), says: “It was a very exciting discovery and one that reveals the hidden potential of Scharf’s papers. By matching diary entries, with sketches, notes and other material in the collection a unique record is revealed. Scharf meticulously recorded almost everything he saw and experienced. In reading his papers, one is able to reconstruct in minute detail ‘a day in the life’ of this remarkable Victorian gentleman.”

The Scharf papers held in the National Portrait Gallery’s Heinz Archive & Library comprise business, personal and family records which reflect not only the history of the Gallery, but also the wider social history of Victorian England.

Scharf was a careful observer of life in his own times and his diaries, notebooks and sketches provide a detailed record of a changing London, everyday Victorian life, and important historic events of the era. They are also an exceptional resource for the study of portraits and portraiture. Alongside his responsibility, as Director, for building-up the National Portrait Gallery’s collection, Scharf also worked in a private capacity on various external projects. He was directly involved in some of the most significant exhibitions of the Victorian period, including Crystal Palace (after its relocation to Sydenham) in 1854 and the Manchester Art Treasures exhibition in 1857.

There are 230 notebooks among Scharf’s papers in which he recorded everything from a sketch of Sir Winston Churchill as a baby to detailed views of Coventry, whose remarkably well-preserved medieval city was completely destroyed by German bombing during World War II.

The Scharf papers are being catalogued as part of the National Cataloguing Grants Programme for Archives, an ongoing project to digitize masses of historical archives from the National Portrait Gallery. You can search the online archives here. It’s surprisingly fascinating stuff, even when it’s not sketches of medieval royal skulls.

I’ve never really gotten the appeal of facial reconstruction outside of forensic need, victim ID and such. They’ve got a portrait (or more than one most likely) by someone who presumably(?) saw him alive. It doesn’t seem like the likeness was embellished too much, he rather looks like a drugged out Larry Fine.

Verisimilitude wasn’t a huge priority in medieval art, though, so contemporary portraiture isn’t really reliable. The general appeal is putting the idealized distant within our grasp. It’s the same reason pioneering color photography and film makes such a strong impression: it’s brings subjects closer to us.

I am admittedly ill informed about the accuracy of such reconstruction, but it seems to me that even if it is accurate with current humans, a significant amount of error could creep in given the different environmental factors likely in previous times. While it isn’t related directly to facial features, consider the effect of improved diet on the average human height.

It’s only my opinion, but dwelling on such things seems to be a desire to show off new technologies more than than gaining a deeper understanding of the actual subject. I’m just weird, but you already knew that.

We know his height, though, from analysis of his bones (he was 6 feet, as coincidence would have it, despite the inadequacies of the period diet). Of course there are surface elements we can’t gauge from the bones — scars, birthmarks, eye and hair color — but facial reconstruction is generally speaking pretty accurate, enough so it is used in criminal forensic investigations.

I don’t think it’s really about showing off. People did this sort of thing long before digital renderings made it easier. They just used bone casts, clay and paint. I think people just want to see themselves in the past.

For one hundred years Egyptian art experts claimed that ancient Egyptian artists had no understanding or ability to make lifelike portraits. Since facial reconstructions have been produced for numerous royal mummies it has become clear that Egyptian artists were producing some exceptional fine (3D) individual portraits. For one hundred years Egyptian art experts have been deluding themselves.

They are quite accurate (70%)and have been tested, using cat scans of skulls, on living subjects in order to gauge accuracy.They are frequently used in battlefield ID and for unidentified human remains. Fleshy parts like ears are the least accurate of course, and the tissue data is based on samples collected in the 80’s so the reconstructions may well still be somewhat fattier than, say, a medieval subject really was. Deep lines on the face are obvious but smaller lines and skin condition are guesswork.

As for height…it’s never been a linear thing tbh. Bronze age Britons were of very similar heights to us, while in medieval times height had dropped several inches with the average man being 5ft 7, still well within modern ranges. It was the Industrial Revolution when people became very short.It is unlikely we will continue to gain much more height, having regained that of our bronze age ancestors.

Thought wasn´t Richard II REALLY buried in the Blackfriars´ abbey in the Scottish Stirling Castle, rather than in Westminster Abbey? There was a legend, and I am sure you are aware of it, claiming that a noble woman, Margery Byset (Bissett), who was presented to the king during his Irish campaign a year or two later (so she had him in a fresh memory), instantly recognized the likeness of Richard II in a beggar travelling around Islay, Scotland. Her husband likewise. All that AFTER Richard´s death in 1400. They immediately took hold of the presumed Richard, gave him better clothes, and presented him to the Scottish king, who lodged this poor madman in the Stirling Castle. The Scots were in unison that this was Richard, using him as a puppet for their anti-Lancastrian ralleys. He died in 1419, and was buried in Blackfriars´. The rumours that Richard II was really set free by the English and allowed to escape were so powerful that the new king, Henry V – whos father Henry Bollingbroke deposed Richard II and allegedly had him starved to death at Pontefract – had the corpose of the starved man from Potefract publically reinter from the place of its previous burial to Westminster Abbey, so that people would see that Richard II was TRULY DEAD, and that THE PONTEFRACT RICHARD WAS THE TRUE RICHARD. I think he wouldn´t have done this if he wasn´t sure that there was something true about the Scottish rumours. What do you think?