Bronze Age tombs so rich in luxurious grave goods they likely belonged to the rulers of the city have been discovered in the ancient city of Dromolaxia Vizatzia on the southeastern coast of Cyprus. The opulent funerary furnishings mark these tombs as among the richest ever found from the Mediterranean Bronze Age.

Bronze Age tombs so rich in luxurious grave goods they likely belonged to the rulers of the city have been discovered in the ancient city of Dromolaxia Vizatzia on the southeastern coast of Cyprus. The opulent funerary furnishings mark these tombs as among the richest ever found from the Mediterranean Bronze Age.

The tombs were found in Area A, a cemetery just outside the city  perimeter. Broken pottery had been churned up by ploughs during previous agricultural work, spurring archaeologists to scan the site with magnetometers which can relay images of objects up to six feet beneath the surface of the soil. The magnetometer map revealed large cavities three to six feet under the surface.

perimeter. Broken pottery had been churned up by ploughs during previous agricultural work, spurring archaeologists to scan the site with magnetometers which can relay images of objects up to six feet beneath the surface of the soil. The magnetometer map revealed large cavities three to six feet under the surface.

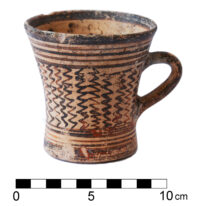

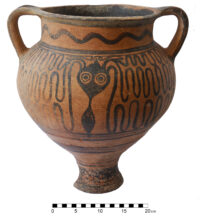

The excavation unearthed three chamber tombs dating to the 14th century B.C. One had been looted, probably in the 19th century, suffering extensive damage to the grave goods and the human remains. The scattered bones were collected for conservation and study. Archaeologists were also able to recovered some jewelry and sherds from pottery imported from the Mycenean cultures of the Aegean, Egypt and Anatolia.

The other two tombs had never been looted, although their chambers had collapsed in antiquity. Between the two tombs, archaeologists found more than 500 artifacts, including local pottery, jewelry, daggers, knives, spearheads and imported pottery and decorative ornaments from the Aegean, Anatolia, Egypt and the Levant. The imported luxury items came from even greater distances too. There was amber from the Baltic Sea, for example, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and deep red carnelian from India.

The other two tombs had never been looted, although their chambers had collapsed in antiquity. Between the two tombs, archaeologists found more than 500 artifacts, including local pottery, jewelry, daggers, knives, spearheads and imported pottery and decorative ornaments from the Aegean, Anatolia, Egypt and the Levant. The imported luxury items came from even greater distances too. There was amber from the Baltic Sea, for example, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and deep red carnelian from India.

The several well-preserved skeletons in the tombs include that of a woman surrounded by dozens of ceramic vessels, jewellery and a round bronze mirror that was once polished. A one-year-old child with a ceramic toy lay beside her.

“Several individuals, both men and women, wore diadems, and some had necklaces with pendants of the highest quality, probably made in Egypt during the 18th dynasty at the time of such pharaohs as Thutmos III and Amenophis IV (Akhenaten) and his wife Nefertiti.”

Embossed images of bulls, gazelles, lions and flowers adorn the diadems. Most of the ceramic vessels came from what we now call Greece, and the expedition also found pots from Turkey, Syria, Palestine and Egypt.

The grave goods also included bronze weapons, some inlaid with ivory, and a gold-framed seal made of the hard mineral haematite with inscriptions of gods and rulers.

Dromolaxia Vizatzia was a Late Bronze Age harbor city on the shores of the Larnaca Salt Lake that flourished from around 1630 to 1150 B.C. Mines in the nearby Troodos Mountains produced copper ore and between 1500 and 1300 B.C., the city prospered as a major center of copper refining and export. Little is known about the city’s form of government, so it’s hard to say whether the people interred in the chamber tombs were royalty, exactly, but they were certainly part of the governing structure.

Dromolaxia Vizatzia was a Late Bronze Age harbor city on the shores of the Larnaca Salt Lake that flourished from around 1630 to 1150 B.C. Mines in the nearby Troodos Mountains produced copper ore and between 1500 and 1300 B.C., the city prospered as a major center of copper refining and export. Little is known about the city’s form of government, so it’s hard to say whether the people interred in the chamber tombs were royalty, exactly, but they were certainly part of the governing structure.