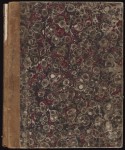

Scientists have confirmed that one book in Harvard’s Houghton Library — Des destinées de l’ame (The Destinies of the Soul) by French poet and essayist Arsène Houssaye, first published in 1879 — is bound in human skin. The book belonged to Dr. Ludovic Bouland, a doctor and book collector from Metz in the northeastern French province of Lorraine who combined his professional vocation with his interest in books and book binding in a rather macabre way. Arsène Houssaye was a personal friend of his. He gave the doctor a copy of his new book and Bouland had it rebound. A handwritten letter signed by Bouland found inside the book describes the new binding:

Scientists have confirmed that one book in Harvard’s Houghton Library — Des destinées de l’ame (The Destinies of the Soul) by French poet and essayist Arsène Houssaye, first published in 1879 — is bound in human skin. The book belonged to Dr. Ludovic Bouland, a doctor and book collector from Metz in the northeastern French province of Lorraine who combined his professional vocation with his interest in books and book binding in a rather macabre way. Arsène Houssaye was a personal friend of his. He gave the doctor a copy of his new book and Bouland had it rebound. A handwritten letter signed by Bouland found inside the book describes the new binding:

“This book is bound in human skin parchment on which no ornament has been stamped to preserve its elegance. By looking carefully you easily distinguish the pores of the skin. A book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering: I had kept this piece of human skin taken from the back of a woman. It is interesting to see the different aspects that change this skin according to the method of preparation to which it is subjected. Compare for example with the small volume I have in my library, Sever. Pinaeus de Virginitatis notis which is also bound in human skin but tanned with sumac.”

There used to be a typed document with the book that elaborated on the source of the skin. The original is gone, but we know from notes that the skin came from “the back of the unclaimed body of a woman patient in a French mental hospital who died suddenly of apoplexy.” The second book Bouland refers to that uses the same skin is now in the Wellcome Library, and according to a 1910 article in a French magazine, Bouland got the piece of skin when he was a medical student at a hospital in Metz. He received his medical degree in 1865, which means he held on to that poor lady’s skin for decades before sectioning it for use in binding at least two books.

There used to be a typed document with the book that elaborated on the source of the skin. The original is gone, but we know from notes that the skin came from “the back of the unclaimed body of a woman patient in a French mental hospital who died suddenly of apoplexy.” The second book Bouland refers to that uses the same skin is now in the Wellcome Library, and according to a 1910 article in a French magazine, Bouland got the piece of skin when he was a medical student at a hospital in Metz. He received his medical degree in 1865, which means he held on to that poor lady’s skin for decades before sectioning it for use in binding at least two books.

The note Bouland wrote on the flyleaf of De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis, a 1663 edition of the influential book by Doctor Séverin Pineau that described the hymen in great anatomical detail (little of it accurate compared to the modern understanding of that intriguing membrane) and provided valuable instruction on how to tell if a virgin had been “corrupted,” is a creepier version of the Des destinées de l’ame explanation:

The note Bouland wrote on the flyleaf of De integritatis et corruptionis virginum notis, a 1663 edition of the influential book by Doctor Séverin Pineau that described the hymen in great anatomical detail (little of it accurate compared to the modern understanding of that intriguing membrane) and provided valuable instruction on how to tell if a virgin had been “corrupted,” is a creepier version of the Des destinées de l’ame explanation:

“This curious little book on virginity, which seemed to me to deserve a binding in keeping with its subject matter, is bound with a piece of woman’s skin that I tanned myself with some sumac.”

As far as Bouland was concerned, a book on the immortal soul and one on hymens were equally well-suited to be bound in the skin of a destitute mentally ill woman who had the misfortune to die of a stroke in the hospital where he was studying.

Two other books at Harvard, one in the Law School Library, one in the Countway Library’s Center for the History of Medicine, had inscriptions identifying them as examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy (the official term for book binding using human skin). The Law School book is Practicarum quaestionum circa leges regias Hispaniae, a treatise on Spanish law by Juan Gutiérrez published in Madrid in 1605. A dramatic inscription on the last page of the book claimed:

Two other books at Harvard, one in the Law School Library, one in the Countway Library’s Center for the History of Medicine, had inscriptions identifying them as examples of anthropodermic bibliopegy (the official term for book binding using human skin). The Law School book is Practicarum quaestionum circa leges regias Hispaniae, a treatise on Spanish law by Juan Gutiérrez published in Madrid in 1605. A dramatic inscription on the last page of the book claimed:

“The bynding of this booke is all that remains of my dear friende Jonas Wright, who was flayed alive by the Wavuma on the Fourth Day of August, 1632. King Mbesa did give me the book, it being one of poore Jonas chiefe possessions, together with ample of his skin to bynd it. Requiescat in pace.”

The book’s binding was DNA tested in 1992 but the results were inconclusive, most likely because of the tanning process. A year after that, a new analytical technique called peptide mass fingerprinting was developed. Peptide mass fingerprinting breaks proteins up into component peptides whose masses can be measured by mass spectrometer and the results compared to a database of known proteins. Two months ago, peptide mass fingerprinting conclusively proved the binding to be sheepskin, not the product of Jonas Wright’s flaying.

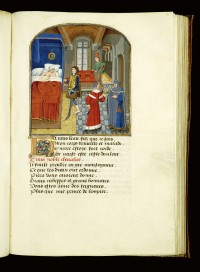

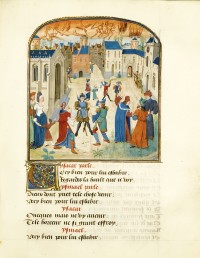

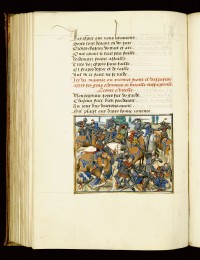

The Countway Library book is a 1597 French translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses which has a faint inscription in pencil on the inside cover stating simply “Bound in human skin,” but experts doubted its accuracy because the binding doesn’t look like other confirmed human leather bindings. Peptide mass fingerprinting proved that it too had a sheepskin binding.

With two of the three claimed human skin bindings proved false, peptide mass fingerprinting was enlisted once again to test the binding of Des destinées de l’ame. This time the peptide mass fingerprint matched the human references, but while it eliminated the usual suspects like sheep and cow, it couldn’t conclusively exclude other primates because we don’t have the comparison data for them.

Although unlikely that the binding was made from a primate source, the samples were further analyzed using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LCMSMS) to determine the order of amino acids, the building blocks of each peptide, which can be different in each species.

“The analytical data, taken together with the provenance of Des destinées de l’ame, make it very unlikely that the source could be other than human,” said [Director of the Harvard Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Resource Laboratory Bill] Lane.