A 2nd century cremation burial in the ancient mountain-top city of Sagalassos, southwestern Turkey, contained a never-before-seen combination of deliberately bent nails, covering tiles and a layer of lime. These features, found individually in other burials in the ancient Mediterranean, collectively suggest the use of magic to keep the deceased from interfering with the living.

A 2nd century cremation burial in the ancient mountain-top city of Sagalassos, southwestern Turkey, contained a never-before-seen combination of deliberately bent nails, covering tiles and a layer of lime. These features, found individually in other burials in the ancient Mediterranean, collectively suggest the use of magic to keep the deceased from interfering with the living.

Founded in the late 5th century B.C. when the region was part of the Achaemenid Empire, by the 2nd century B.C., Sagalassos was an urban center of the Hellenistic Attalid Kingdom that was bequeathed to the Roman Republic with the death of King Attalos III in 133 B.C. Augustus incorporated it into the Roman province of Galatia in 25 B.C., and the city thrived in the Roman Imperial era. Major public buildings, city squares and streets were constructed and a new pottery industry mass-producing what became known as Sagalassos Red Slip Ware prospered, transforming Sagalassos into the pre-eminent city of the region. Under Hadrian the city saw another boom of public construction. The library, nymphaeum, Temple of Apollo and the enormous baths were built starting under Hadrian. The baths were completed and the theater built under Marcus Aurelius.

The city declined in importance in late antiquity, but continued to produce its eponymous pottery into the 7th century A.D. when it was severely damaged by an earthquake. It was much reduced in population after that and became largely agrarian until it was finally abandoned altogether in the 13th century when its fortress was destroyed by the Seljuk sultanate. Many of its remains were left undisturbed in subsequent centuries, and the Catholic University of Leuven has been systematically excavating the site since 1990.

In 2010, KU Leuven’s Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project embarked on a new exploration of the northeastern periphery of the city. The area was originally dedicated to agricultural terracing, but as the city expanded in the Hellenistic period, it began to be used for funerary purposes. The excavation ultimately uncovered inhumation and cremation burials dating from the late Hellenistic (c. 150–25 B.C.) continuously through the Late Roman (c. 300–450/475 A.D.) period.

In 2010, KU Leuven’s Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project embarked on a new exploration of the northeastern periphery of the city. The area was originally dedicated to agricultural terracing, but as the city expanded in the Hellenistic period, it began to be used for funerary purposes. The excavation ultimately uncovered inhumation and cremation burials dating from the late Hellenistic (c. 150–25 B.C.) continuously through the Late Roman (c. 300–450/475 A.D.) period.

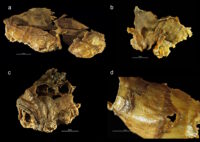

The unusual cremation burial was in situ, the human remains burned on a pyre and then buried. The distribution of the charred bone remains indicate they were not collected or moved, which is atypical for 2nd century cremations.

Usually the cremated bones were moved into a cinerary urn before burial. Instead, here the pyre was covered with 24 flat bricks arranged in four rows. The undersides of the tiles were discolored from the heat, meaning they were placed on top of the pyre while the embers were still smoldering. The bricks were then covered with a thick layer of solidified lime, not the thin, temporary layer typically used to cover the cinerary remains before they were recovered for burial. This lime layer over the bricks permanently sealed in the cremated remains as much as a solid coffin or tomb would have.

Grave goods found include a 2nd century coin, a few small ceramic vessels dating to the 1st century, two blown glass vessels and a hinged object. Stratigraphy indicates they were buried in the first half of the 2nd century A.D., a time when these types of artifacts were common in burials.

Grave goods found include a 2nd century coin, a few small ceramic vessels dating to the 1st century, two blown glass vessels and a hinged object. Stratigraphy indicates they were buried in the first half of the 2nd century A.D., a time when these types of artifacts were common in burials.

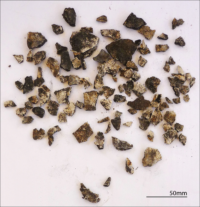

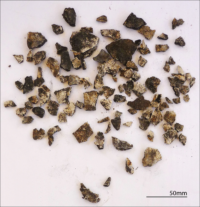

Not at all common are 41 broken and bent nails found along the edges of the burn area. Twenty-five of the nails were bent deliberately at a 90° angle and the heads twisted off. Sixteen were deliberately bent or twisted but still complete with their heads. They could not have been used for a practical purpose (for example, in the construction of the pyre) and their distribution around the pyre’s perimeter points to them having been placed.

“The burial was closed off with not one, not two, but three different ways that can be understood as attempts to shield the living from the dead — or the other way around,” study first author Johan Claeys(opens in new tab), an archaeologist at Catholic University Leuven (KU Leuven) in Belgium, told Live Science in an email. Although each of these practices is known from Roman-era cemeteries — cremation in place, coverings of tiles or plaster, and the occasional bent nail — the combination of the three has not been seen before and implies a fear of the “restless dead,” he said. […]

Claeys thinks that the man in this strange cremation grave was likely buried by his next of kin in a ceremony that would have taken days to prepare and carry out. The set of beliefs that encouraged people at Sagalassos to bury this man in an unconventional way are best understood as a form of magic(opens in new tab), or an act intended to have specific effects because of a supernatural connection. It is possible that his odd burial was made to counteract an unusual or unnatural death; however, the researchers found no evidence of trauma or disease on the bones. Unfortunately, even though the “magic cremation” overlaps in time with other graves, Claeys said that “it cannot be established with certainty whether or not any family members were buried nearby,” as DNA is usually destroyed by high temperatures in ancient cremations.

Claeys thinks that the man in this strange cremation grave was likely buried by his next of kin in a ceremony that would have taken days to prepare and carry out. The set of beliefs that encouraged people at Sagalassos to bury this man in an unconventional way are best understood as a form of magic(opens in new tab), or an act intended to have specific effects because of a supernatural connection. It is possible that his odd burial was made to counteract an unusual or unnatural death; however, the researchers found no evidence of trauma or disease on the bones. Unfortunately, even though the “magic cremation” overlaps in time with other graves, Claeys said that “it cannot be established with certainty whether or not any family members were buried nearby,” as DNA is usually destroyed by high temperatures in ancient cremations.

“Regardless of whether the cause of [the man’s] death was traumatic, mysterious or potentially the result of a contagious illness or punishment,” the researchers concluded in the study, it appears to have left “the living fearful of the deceased’s return.”

The burial findings have been published in the journal Antiquity and can be read here.

A rescue archaeology excavation at the site of railroad expansion in the Askizsky region of Khakassia in Siberia has unearthed the grave of a Late Bronze Age man buried wearing a “charioteer’s belt,” a flat bronze plate with two curved hooks at the end reminiscent of a yoke used to harness draft animals. This device is believed to have been used by charioteers to tie their reins to their waists so their hands were free for combat.

A rescue archaeology excavation at the site of railroad expansion in the Askizsky region of Khakassia in Siberia has unearthed the grave of a Late Bronze Age man buried wearing a “charioteer’s belt,” a flat bronze plate with two curved hooks at the end reminiscent of a yoke used to harness draft animals. This device is believed to have been used by charioteers to tie their reins to their waists so their hands were free for combat. The tomb is dated to between the 11th and the 8th century B.C., a time when the Lugav culture was dominant in the area. The site under excavation contains material remains of a cemetery as well as a settlement from this period, and the Lugav barrows in the cemetery can be grouped into three stages — the transition to the Lugav culture, the Lugav middle stage and the late stage, when characteristics from the next culture (Tagar) appear mingled with the Lugav features. The charioteer’s tomb is from the middle stage.

The tomb is dated to between the 11th and the 8th century B.C., a time when the Lugav culture was dominant in the area. The site under excavation contains material remains of a cemetery as well as a settlement from this period, and the Lugav barrows in the cemetery can be grouped into three stages — the transition to the Lugav culture, the Lugav middle stage and the late stage, when characteristics from the next culture (Tagar) appear mingled with the Lugav features. The charioteer’s tomb is from the middle stage.Aleksey Timoshchenko, an archaeologist at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences, told Live Science in an email that the object was found in its original placement at the waist of the person in the undisturbed grave.

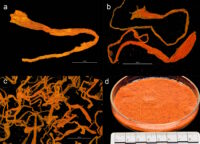

No chariot remains have been found in Siberian burials from this era, and for years the hooked bronze belt was classified by Russian archaeologists as an unknown object. Its use was identified by comparison with artifacts found in Chinese chariot burials and bronzes from the Zhou Dynasty (11th-3rd century B.C.).

No chariot remains have been found in Siberian burials from this era, and for years the hooked bronze belt was classified by Russian archaeologists as an unknown object. Its use was identified by comparison with artifacts found in Chinese chariot burials and bronzes from the Zhou Dynasty (11th-3rd century B.C.).