The Library of Trinity College Dublin has digitized one of the greatest medieval masterpieces in its collection: The Book of St. Albans, handwritten and illustrated by chronicler, scribe and illuminator Matthew Paris. The artwork and verse text was previously only available in a black-and-white facsimile edition made in 1924 that cannot begin to convey the bright colors of the original.

The Library of Trinity College Dublin has digitized one of the greatest medieval masterpieces in its collection: The Book of St. Albans, handwritten and illustrated by chronicler, scribe and illuminator Matthew Paris. The artwork and verse text was previously only available in a black-and-white facsimile edition made in 1924 that cannot begin to convey the bright colors of the original.

Born in England, Matthew Paris was still a teenager when he entered monastic life as a monk at the Benedictine abbey of St. Albans in Hertofordshire. He lived at St. Albans from 1217 until his death in 1259, where he wrote all of his known works including his seminal history of the world, the Chronica Majora (ca. 1240-53) and the Book of St. Albans (ca. 1230-1259).

Alban lived in the 4th century and is venerated as the first English Christian martyr. The monastery dedicated to him was founded by King Offa of Mercia at the end of the 8th century. It was an important site of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, attracting the nobility and aristocracy of England. They even offered accommodations for royal women, the only monastic house in England to do so.

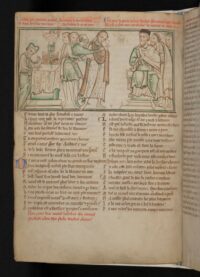

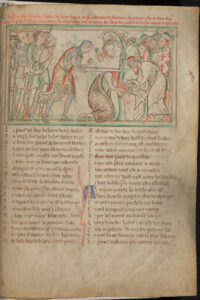

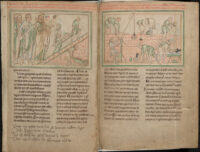

The Book of St. Albans, which included also a Life of St Amphibalus (according to some sources the man who converted Alban) and other writings about the history of the abbey, is composed of 77 leaves with 54 illustrations. Matthew’s drawings are narrative scenes that take up a third of the top of the page. Some are in comic book-style double panels. He enhanced his line drawings by coloring them with washes of green, red, blue and silver and gold accents. The colors are brilliantly preserved in the manuscript.

Each scene is peopled with human figures in dynamic motion, and they are not just saints, kings and extras. Matthew Paris included people from all walks of life — sailors, soldiers, bell ringers and builders. His illustration of Offa directing the construction of the first St. Albans church is a unique graphic representation of medieval construction techniques, tools and materials. It also features some solid gore like Alban’s severed head and his executioner’s eyeballs falling out into his hand.

Each scene is peopled with human figures in dynamic motion, and they are not just saints, kings and extras. Matthew Paris included people from all walks of life — sailors, soldiers, bell ringers and builders. His illustration of Offa directing the construction of the first St. Albans church is a unique graphic representation of medieval construction techniques, tools and materials. It also features some solid gore like Alban’s severed head and his executioner’s eyeballs falling out into his hand.

The text is in both Anglo-Norman French, the language of the secular ruling class, and in Latin, the language of the clergy. It is a small enough volume to be portable, and there is evidence the monastery did lend it to important patrons. A note on Folio 2r records that the volume was loaned on one occasion to Sanchia of Provence (d.1261), the Countess of Cornwall, who was the sister of Queen Eleanor of Provence (1223-1291).

The note says she kept the book until Whitsuntide and must have returned it because the manuscript remained at St. Albans Abbey until the monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1539. Unlike the relics of saints Alban and Amphibalus, the manuscript survived the orgy of destruction. It was owned by astronomer John Dee (1527-1609) at some point, and then by Bishop James Ussher who bought it in 1626. (Ussher’s claim to fame is having counted up the generations in the Bible to determine conclusively that the world was created on October 22, 4004 B.C.) Ussher bequeathed his library to Trinity College and the Matthew Paris manuscript officially entered the library’s rare book collection in 1661.

The note says she kept the book until Whitsuntide and must have returned it because the manuscript remained at St. Albans Abbey until the monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1539. Unlike the relics of saints Alban and Amphibalus, the manuscript survived the orgy of destruction. It was owned by astronomer John Dee (1527-1609) at some point, and then by Bishop James Ussher who bought it in 1626. (Ussher’s claim to fame is having counted up the generations in the Bible to determine conclusively that the world was created on October 22, 4004 B.C.) Ussher bequeathed his library to Trinity College and the Matthew Paris manuscript officially entered the library’s rare book collection in 1661.

Browse the digitized Book of St. Albans here.