The skeletal remains of a late medieval man with an iron prosthetic hand have been discovered in Freising, Bavaria. There are only about 50 comparable prostheses known from Central Europe in the late medieval and early modern periods. They range from immobile shaped devices to articulated ones with mechanical elements. This one is immobile.

The skeletal remains of a late medieval man with an iron prosthetic hand have been discovered in Freising, Bavaria. There are only about 50 comparable prostheses known from Central Europe in the late medieval and early modern periods. They range from immobile shaped devices to articulated ones with mechanical elements. This one is immobile.

The grave was unearthed in 2017 during pipeline work near the 17th century Baroque parish church of St. Georg in the central square of Freising’s old town. Examination of the remains at the conservation workshops of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation (BLfD) found the deceased was an adult male between 30 and 50 years of age. Radiocarbon dating revealed he died between 1450 and 1620.

The grave was unearthed in 2017 during pipeline work near the 17th century Baroque parish church of St. Georg in the central square of Freising’s old town. Examination of the remains at the conservation workshops of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation (BLfD) found the deceased was an adult male between 30 and 50 years of age. Radiocarbon dating revealed he died between 1450 and 1620.

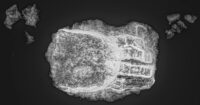

The corroded lump of metal at the end of the skeleton’s left arm was given a rough, preliminary cleaning and stabilized so it could be X-rayed and studied for any traces of leather or textiles. X-rays taken in 2021 revealed that the hand prosthesis was hollow with four fingers — the index, middle, ring and pinky. They were fabricated from sheet metal and are immobile. The fingers are parallel to each other and appear to be slightly curved.

The corroded lump of metal at the end of the skeleton’s left arm was given a rough, preliminary cleaning and stabilized so it could be X-rayed and studied for any traces of leather or textiles. X-rays taken in 2021 revealed that the hand prosthesis was hollow with four fingers — the index, middle, ring and pinky. They were fabricated from sheet metal and are immobile. The fingers are parallel to each other and appear to be slightly curved.

A thumb bone from his left hand is inside the corroded prosthetic hand. BlfD conservators believe it was covered with leather and tied to the stump of the left hand with straps. Traces of a wrinkled, gauze-like textile inside the fingers are probably the remains of a fabric used to cushion the stump. An iron prosthetic like this, even without articulating elements, was expensive, and given how many men of soldiering age were mercenaries or pledged fighters for the endlessly squabbling aristocracy of late medieval Germany, the deceased may have lost his hand in battle. So far, researchers have not been able to determine how the wound was inflicted.

A thumb bone from his left hand is inside the corroded prosthetic hand. BlfD conservators believe it was covered with leather and tied to the stump of the left hand with straps. Traces of a wrinkled, gauze-like textile inside the fingers are probably the remains of a fabric used to cushion the stump. An iron prosthetic like this, even without articulating elements, was expensive, and given how many men of soldiering age were mercenaries or pledged fighters for the endlessly squabbling aristocracy of late medieval Germany, the deceased may have lost his hand in battle. So far, researchers have not been able to determine how the wound was inflicted.

One well-known amputee with a prosthetic hand from this period was the Imperial Knight Götz von Berlichingen, also known Götz of the Iron Hand. He fought for Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and later sold his sword to a long list of princes, dukes and margraves in the wars of the late 15th and 16th century. He lost his right hand at the wrist in 1504 when a cannon ball struck it during the siege of Landshut, a Bavarian city just 25 miles from Freising. His first prosthetic was made by a local blacksmith out of iron. Later he upgraded to a high-tech model with fingers that could curl up, allowing him to hold reigns, weapons, even a quill pen. Both of the Götz’s iron hands are on display in his ancestral home, today the castle museum of the Götzenburg in Jagsthausen.

One well-known amputee with a prosthetic hand from this period was the Imperial Knight Götz von Berlichingen, also known Götz of the Iron Hand. He fought for Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and later sold his sword to a long list of princes, dukes and margraves in the wars of the late 15th and 16th century. He lost his right hand at the wrist in 1504 when a cannon ball struck it during the siege of Landshut, a Bavarian city just 25 miles from Freising. His first prosthetic was made by a local blacksmith out of iron. Later he upgraded to a high-tech model with fingers that could curl up, allowing him to hold reigns, weapons, even a quill pen. Both of the Götz’s iron hands are on display in his ancestral home, today the castle museum of the Götzenburg in Jagsthausen.