The Treasures of St. Cuthbert, a collection of relics of the saint and his medieval sanctuary, have gone back on display at Durham Cathedral after six years out of public view. The exhibition is part of Durham Cathedral’s Open Treasure project, an ambitious £11 million redesign that transformed the display spaces in the 11th century masterpiece of Norman architecture to showcase its exceptional collection including Anglo-Saxon carved stones, original copies of Magna Carta and the Forest Charter and illuminated gospels dating as far back as the 7th century. The new exhibition also opens to visitors previously inaccessible areas of the former monastery like the Monk’s Dormitory and the Great Kitchen, grand medieval rooms that managed against all odds to survive the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the organizational, spiritual and iconoclastic upheaval of the Reformation, Cromwell’s suppression of the church and use of the cathedral as a POW camp for Scottish prisoners during the Civil War and a number of destructive architectural mutilations in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Treasures of St. Cuthbert, a collection of relics of the saint and his medieval sanctuary, have gone back on display at Durham Cathedral after six years out of public view. The exhibition is part of Durham Cathedral’s Open Treasure project, an ambitious £11 million redesign that transformed the display spaces in the 11th century masterpiece of Norman architecture to showcase its exceptional collection including Anglo-Saxon carved stones, original copies of Magna Carta and the Forest Charter and illuminated gospels dating as far back as the 7th century. The new exhibition also opens to visitors previously inaccessible areas of the former monastery like the Monk’s Dormitory and the Great Kitchen, grand medieval rooms that managed against all odds to survive the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the organizational, spiritual and iconoclastic upheaval of the Reformation, Cromwell’s suppression of the church and use of the cathedral as a POW camp for Scottish prisoners during the Civil War and a number of destructive architectural mutilations in the 18th and 19th centuries.

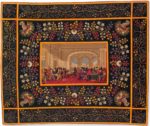

The Open Treasure experience has been delighting visitors since July 2016, but St. Cuthbert’s treasures are so delicate they require stringent conservation conditions. Conservators waited a full year, monitoring climactic conditions in the new permanent home for the saint’s relics to ensure they were ideal for their long-term preservation. On Saturday, July 29th, the Treasures of St. Cuthbert reopened in their new abode: the Cathedral’s extraordinary Great Kitchen, a massive space with an octagonal ceiling glorious enough to make numerologist angels weep. For centuries the kitchen produced food for hundreds of Benedictine monks and for the deans and canons that followed them after the Reformation. It was still in use as a kitchen well into the 1940s. That continuous use saved it for posterity and it is now one of exactly two surviving medieval monastery kitchens in the UK. (Thanks again for reducing all those monasteries to rubble, Henry VIII!)

The Open Treasure experience has been delighting visitors since July 2016, but St. Cuthbert’s treasures are so delicate they require stringent conservation conditions. Conservators waited a full year, monitoring climactic conditions in the new permanent home for the saint’s relics to ensure they were ideal for their long-term preservation. On Saturday, July 29th, the Treasures of St. Cuthbert reopened in their new abode: the Cathedral’s extraordinary Great Kitchen, a massive space with an octagonal ceiling glorious enough to make numerologist angels weep. For centuries the kitchen produced food for hundreds of Benedictine monks and for the deans and canons that followed them after the Reformation. It was still in use as a kitchen well into the 1940s. That continuous use saved it for posterity and it is now one of exactly two surviving medieval monastery kitchens in the UK. (Thanks again for reducing all those monasteries to rubble, Henry VIII!)

Henry VIII’s dissolution minions are also responsible for the current condition of one of the most important relics on display. The Commissioners ordered that Saint Cuthbert’s tomb in the cathedral, one of the richest and most beloved pilgrimage sites in the country, be destroyed. The employed a local goldsmith sledgehammer Cuthbert’s wooden coffin, carved by the monks of the famous Lindisfarne Priory at the end of the 7th century A.D., open because they were sure there were treasures to be looted inside the wood of the coffin. There weren’t. All they got for their brutality was whatever satisfaction they derived from busting the greatest example of Anglo-Saxon woodwork in Britain to bits.

Henry VIII’s dissolution minions are also responsible for the current condition of one of the most important relics on display. The Commissioners ordered that Saint Cuthbert’s tomb in the cathedral, one of the richest and most beloved pilgrimage sites in the country, be destroyed. The employed a local goldsmith sledgehammer Cuthbert’s wooden coffin, carved by the monks of the famous Lindisfarne Priory at the end of the 7th century A.D., open because they were sure there were treasures to be looted inside the wood of the coffin. There weren’t. All they got for their brutality was whatever satisfaction they derived from busting the greatest example of Anglo-Saxon woodwork in Britain to bits.

Saint Cuthbert was Prior of Lindisfarne when he died on March 20, 687. His cause of death is believed to have been tuberculosis. He was buried in the priory and slumbered peacefully for 11 years until the monks reopened the coffin and found his body had not decayed. The discovery of the incorrupt body launched the cult of Cuthbert and garnered him a sainthood. Unprepared for an intact body (they likely had planned to transfer his bones into a small ossuary only to find a fully enfleshed corpse instead), they hastily scared up a new coffin made of oak and carved with simple but elegant linear drawings of the Evangelists and their symbols, Christ, saints and angels. The figures are labelled in both Latin and Anglo-Saxon runes. These are the earliest carvings depicting Christ found outside of Rome.

Saint Cuthbert was Prior of Lindisfarne when he died on March 20, 687. His cause of death is believed to have been tuberculosis. He was buried in the priory and slumbered peacefully for 11 years until the monks reopened the coffin and found his body had not decayed. The discovery of the incorrupt body launched the cult of Cuthbert and garnered him a sainthood. Unprepared for an intact body (they likely had planned to transfer his bones into a small ossuary only to find a fully enfleshed corpse instead), they hastily scared up a new coffin made of oak and carved with simple but elegant linear drawings of the Evangelists and their symbols, Christ, saints and angels. The figures are labelled in both Latin and Anglo-Saxon runes. These are the earliest carvings depicting Christ found outside of Rome.

When the Viking raiders struck the priory in the 9th century, the monks took Cuthbert’s coffin and his relics with them when they fled in 875. The traveled extensively, stopping at major cities along the way so pilgrims could flock to see the saint’s miraculous body. Cuthbert’s posthumous itinerancy came to a close in 995 when his remains were settled in Durham. Just over a century after that, his body, still in the Lindisfarne coffin, was placed into a new coffin and installed in a new shrine in the Norman cathedral.

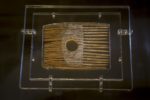

After Henry’s pillage crew came away empty-handed from the destruction of the shrine, Cuthbert’s remains, still undecayed and still inside the damaged coffin, were placed inside yet another coffin and reburied in the cathedral. The tomb was opened again twice in the 19th century, mainly out of sheer curiosity. It was the first of these reopenings in 1827 that discovered the saint’s gold and garnet pectoral cross deep in the folds of his garments (turns out Henry’s Commissioners sucked at looting, despite their extensive experience in the field), a silver portable altar and Cuthbert’s elephant ivory comb in the coffin.

After Henry’s pillage crew came away empty-handed from the destruction of the shrine, Cuthbert’s remains, still undecayed and still inside the damaged coffin, were placed inside yet another coffin and reburied in the cathedral. The tomb was opened again twice in the 19th century, mainly out of sheer curiosity. It was the first of these reopenings in 1827 that discovered the saint’s gold and garnet pectoral cross deep in the folds of his garments (turns out Henry’s Commissioners sucked at looting, despite their extensive experience in the field), a silver portable altar and Cuthbert’s elephant ivory comb in the coffin.

After the second reopening in 1899, the remains of the Lindisfarne coffin, now in fragments, were removed. Restoration attempts, one as recently as the 1980s, used damaging methods that today’s conservators eschew. Still, the coffin was on display for many years in Durham Cathedral, set high up so the carving was all but impossible to see in any kind of detail. The fragments have been re-conserved now, puzzled together using a non-invasive, reversible approach and put on display in a bespoke, climate-controlled case at eye level so visitors can revel in the unique decoration of the most important surviving wooden artifact from the Anglo-Saxon period.

After the second reopening in 1899, the remains of the Lindisfarne coffin, now in fragments, were removed. Restoration attempts, one as recently as the 1980s, used damaging methods that today’s conservators eschew. Still, the coffin was on display for many years in Durham Cathedral, set high up so the carving was all but impossible to see in any kind of detail. The fragments have been re-conserved now, puzzled together using a non-invasive, reversible approach and put on display in a bespoke, climate-controlled case at eye level so visitors can revel in the unique decoration of the most important surviving wooden artifact from the Anglo-Saxon period.

Also on display in the Great Kitchen is the pectoral cross, one of the greatest and most significant examples of Anglo-Saxon metalwork marking the transition from their traditional iconography and decorative style to Christianity and bearing the wear and tear of Cuthbert’s constant use of the piece. The comb, which looks a tad on the grubby side but must have been quite a fancy thing in the saint’s day because it was likely manufactured in North African in the 4th century, and the portable altar.

Also on display in the Great Kitchen is the pectoral cross, one of the greatest and most significant examples of Anglo-Saxon metalwork marking the transition from their traditional iconography and decorative style to Christianity and bearing the wear and tear of Cuthbert’s constant use of the piece. The comb, which looks a tad on the grubby side but must have been quite a fancy thing in the saint’s day because it was likely manufactured in North African in the 4th century, and the portable altar.

Then there are the artifacts associated with the shrine that aren’t directly connected to Saint Cuthbert in person, for example an incredibly rare group of embroidered silk and gold vestments donated to the shrine in the 10th century by King Athelstan and a magnificent 12th century knocker from the door of the sanctuary in the shape of the head of a leonine hellbeast complete with a little guy’s legs sticking out of the fearsome creature’s mouth. The legs are each devoured by the mouths of the double-headed snake which form the knocker itself.

Then there are the artifacts associated with the shrine that aren’t directly connected to Saint Cuthbert in person, for example an incredibly rare group of embroidered silk and gold vestments donated to the shrine in the 10th century by King Athelstan and a magnificent 12th century knocker from the door of the sanctuary in the shape of the head of a leonine hellbeast complete with a little guy’s legs sticking out of the fearsome creature’s mouth. The legs are each devoured by the mouths of the double-headed snake which form the knocker itself.

There’s even a dragon-slaying sword, the Conyers Falchion, a 13th century sword that legend has it was used by Sir John Conyers to kill the Sockburn Worm. This is the story that inspired Lewis Carroll’s poem Jabberwocky. Decorated with the coat of arms of the Holy Roman Empire on one side of the pommel and that of England on the other, the falchion was for centuries ceremonially

There’s even a dragon-slaying sword, the Conyers Falchion, a 13th century sword that legend has it was used by Sir John Conyers to kill the Sockburn Worm. This is the story that inspired Lewis Carroll’s poem Jabberwocky. Decorated with the coat of arms of the Holy Roman Empire on one side of the pommel and that of England on the other, the falchion was for centuries ceremonially  presented to the new bishop of Durham when he first crossed the boundary into his diocese. The last bishop to be so fortunate is the current one, Bishop Paul Butler, who crossed the River Tees into his new diocese in 2014. From now on, the dragon-slaying sword is staying put in the Great Kitchen. Future bishops will have to make do with a replica.

presented to the new bishop of Durham when he first crossed the boundary into his diocese. The last bishop to be so fortunate is the current one, Bishop Paul Butler, who crossed the River Tees into his new diocese in 2014. From now on, the dragon-slaying sword is staying put in the Great Kitchen. Future bishops will have to make do with a replica.