An oil sketch in the Museum Bredius in The Hague discounted as a copy has been revealed to be an autograph work by Rembrandt. The Raising of the Cross, once widely accepted as a real Rembrandt, had been dismissed as a bad copy for 50 years until art historian and former museum curator Jeroen Giltaij began to investigate it for a book he was writing on Rembrandt’s oeuvre. He thought the quality of painting marked it as a work by the master. Museum Bredius conservators cleaned and restored the work, removing discolored varnish layers and later overpainting to reveal the painting in its “naked” unretouched state. Rembrandt’s distinctive brushstrokes are now clearly visible.

An oil sketch in the Museum Bredius in The Hague discounted as a copy has been revealed to be an autograph work by Rembrandt. The Raising of the Cross, once widely accepted as a real Rembrandt, had been dismissed as a bad copy for 50 years until art historian and former museum curator Jeroen Giltaij began to investigate it for a book he was writing on Rembrandt’s oeuvre. He thought the quality of painting marked it as a work by the master. Museum Bredius conservators cleaned and restored the work, removing discolored varnish layers and later overpainting to reveal the painting in its “naked” unretouched state. Rembrandt’s distinctive brushstrokes are now clearly visible.

Infrared reflectography (IRR) and X-ray scans of the sketch performed by Rotterdam-based art restorer Johanneke Verhave reveal that its composition initially matched that of the Munich version. During the painting process of the sketch, the composition changed to move the horseman from left of the cross facing the viewer to the bottom right corner with the horseman looking up at the cross, his and his horse’s backs to the viewer. The horseman took the place of a dog that was in the original design. An almost identical rider appears in a 1629 etching by Rembrandt.

From the first half of the 19th century, the work was believed to be an authentic painting by Rembrandt. At the time, art historians thought it was a study for Rembrandt’s 1633 The Raising of the Cross , a piece almost double the size of the sketch that is now in the Alte Pinakothek museum in Munich. When the oil sketch was acquired by collector and museum founder/director Abraham Bredius in 1921, he had no doubt that it was painted by the master’s hand, but he thought it was made around 1640, a new and improved version of the Munich piece rather than a preparatory sketch for it.

From the first half of the 19th century, the work was believed to be an authentic painting by Rembrandt. At the time, art historians thought it was a study for Rembrandt’s 1633 The Raising of the Cross , a piece almost double the size of the sketch that is now in the Alte Pinakothek museum in Munich. When the oil sketch was acquired by collector and museum founder/director Abraham Bredius in 1921, he had no doubt that it was painted by the master’s hand, but he thought it was made around 1640, a new and improved version of the Munich piece rather than a preparatory sketch for it.

The attribution to Rembrandt was cast into doubt by scholars in the 1960s and by the end of the decade it had been removed from the artist’s catalogue raisonné and downgraded in status to, as art historian Horst Gerson described it in 1969, a “crude imitation, vaguely based on Rembrandt” made by a nameless follower.

Well the joke’s on Horst, because it is neither crude nor an imitation. Experts from the Rijksmuseum have also performed a technical study of the painting and they too concluded it is an autograph work by Rembrandt. Dendrochronological analysis of the wood panel it was painted on dates the felling of the tree to 1634. The plank had to be seasoned before use, so it was probably painted between 1642 and 1645. It could not have been a preparatory sketch for The Raising of the Cross Rembrandt painted in 1633.

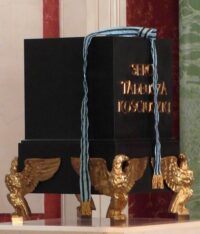

The re-authenticated Rembrandt is now on display at the Museum Bredius in a short exhibition dedicated to the oil sketch and the research that restored it to its birthright.