In August of 1892, a duel took place in Liechtenstein. The two adversaries took the field armed with rapiers to take satisfaction in blood over an unpardonable outrage: a dispute over a flower arrangement.

The precise nature of the disagreement has been lost in the mists of time. All we know is that Princess Pauline Metternich, granddaughter of Napoleonic-era Austrian statesman Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and Countess Anastasia Kilmannsegg, wife of the Statthalter of Lower Austria, had conflicting visions of how the flowers should be arranged at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater of 1892. Both of the ladies were high society fixtures in Paris and Vienna of the late 19th century. Both of them volunteered for a number of charitable organizations and were active supporters of the arts.

The precise nature of the disagreement has been lost in the mists of time. All we know is that Princess Pauline Metternich, granddaughter of Napoleonic-era Austrian statesman Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and Countess Anastasia Kilmannsegg, wife of the Statthalter of Lower Austria, had conflicting visions of how the flowers should be arranged at the Viennese International Exhibition of Music and Theater of 1892. Both of the ladies were high society fixtures in Paris and Vienna of the late 19th century. Both of them volunteered for a number of charitable organizations and were active supporters of the arts.

The Internationale Musik und Theaterwesenausstellung was the artistic event of fin de siècle Vienna, and while little remembered today, its influence was enormous and has played a foundational role in the perception of musical culture extending to the present. Inspired by the madly popular trend for world fairs launched by the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851, the Viennese International Exhibition was a showcase of the greatest music Europe’s most musical city could offer and the first large-scale marketing blitz to monetize and promote that artistic output. It was the first and only world’s fair ever to focus exclusively on music and theater, and the very idea of “classical music,” defined as European music from the mid-16th century through the end of the 19th, was birthed there on May 7th, 1892. By the time the exhibition ended on October 9th, the notion was firmly established, as was the image of Vienna as the capital of European music.

Princess Pauline and Countess Kilmannsegg held important volunteer positions at this once-in-a-lifetime event. The Princess served as Honorary President, the Countess as President of the Ladies Committee. It was the Princess’ idea, in fact, the expand the purview of the festival to cover theater as well as music, and to make it international (in the Eurocentric sense) instead of a the original idea which was a far more modest exhibition dedicated to the history of Austrian music. Because of her operas like Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci and Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana were staged to great acclaim at the Exhibition. (Not in a single bill together, though. The classic CavPag pairing debuted at the Metropolitan Opera in New York a year later.)

The Princess also founded the Flower Parade down the main street of the Prater, a tradition she began in 1886 that continues to this day, and she was described in one paper (before the duel) as “having inherited a courage which borders on insanity from her father, Count Sandor, who was famous for his hair-brained extravagances.” So maybe that explains why whatever the Countess had to say about the flower arrangements at the International Exhibition so deeply appalled the Princess and why she was willing to take it to the point of bloodshed.

Princess Pauline Metternich, then 56 years of age and so great a doyenne in Austrian society that she was held in far higher social regard than the Empress Elizabeth, challenged Countess Kilmannsegg to a duel. As dueling was illegal in Austria, they and their seconds Princess Schwarzenberg and Countess Kinsky respectively, went to Vaduz, capital of Liechtenstein, to let their rapiers do the talking.

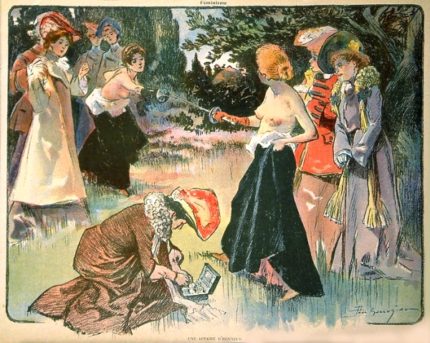

Presiding over the encounter was Baroness Lubinska, a Polish noblewoman who had been sent for from Warsaw to oversee the violence. The Baroness was a medical doctor, a rarity for women at that time, and rarer than that, she practiced Listerite principles. This was an important asset for someone who might have to field-dress rapier wounds. The Baroness had seen first-hand how easily infection could set in with even superficial cuts in battle because dirty clothes would be stabbed into the wound and make it fester, so she told the male footmen and coachman to turn around and ordered the dueling parties to strip to the waist.

This was not to be a duel to the death. The aim was first blood only. Princess Metternich and Countess Kilmannsegg, both topless, picked up their rapiers and engaged. After a few exchanges, one received a small cut to the nose, the other one to the arm. Contemporary reports, sparse on detail, are inconsistent about which one of them took which blow. Either way, first blood had been drawn by Princess Metternich. She was declared the winner and fighting ceased. The doctor dressed their wounds and the seconds suggested the ladies embrace and kiss. They did so and thus ended the great Topless Flower Arrangement Duel of 1892.

The encounter caused a sensation. It became known as the Emancipated Duel and scenes of topless women swordfighting became very popular on stage, screen and in naughty postcards.

EDIT: Darnit, too many smart people read this blog. It seems there is no hard evidence for this duel ever having taken place. The contemporary accounts were basically gossip. I can’t help but hope that the Princess denied it happened to preserve her privacy. Yeah, that’s the ticket. PISTOLES AT DAWN for anyone who tries to persuade me otherwise.