The Detroit Institute of Art holds in its collection a small egg tempera on panel work by 15th century Venetian painter Antonio Vivarini. It’s a scene from the life of Saint Monica, long-suffering mother of Saint Augstine, in which she coverts her pagan husband Patricius on his deathbed. This was not originally a stand-alone panel painting. It was part of the predella (small action scenes in the footer of an altarpiece whose main panels feature large-scale individual figures) of a polyptych which is no longer extant. It was cut out of the frame leaving the bottom of panel is therefore wider than the top.

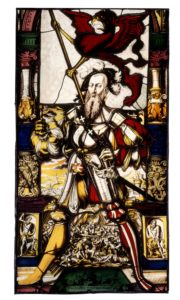

The original altarpiece is believed to have been in the Church of Santo Stefano in Venice. The church was extensively rebuilt in the early 15th century at a time when the cult of Saint Monica reached its zenith in popularity. When construction was completed around 1440, there was a chapel with an altar dedicated to St Monica in the left aisle. Francesco Sansovino, writing in 1581, noted that the altarpiece in the chapel had been painted by Giovanni and Antonio Vivarini (phrased as brothers, but Giovanni d’Alemagna was actually Antonio’s German brother-in-law). In the 17th century, art historian Carlo Ridolfi described Vivarini and his brother-in-law’s art in the chapel as a statue of Saint Monica standing surrounded by “picciole historiette” (wee historylets) depicting scenes from her life.

The chapel was moved to the right aisle in the 18th century but the altarpiece did not move with it. The new chapel got new art, and the old was given away to an Augustinian lay community who cut it up and sold it piecemeal. Art historians in the 20th century have traced the scattered components, identifying five panels of the lost altarpiece in museums around the world: The Marriage of St Monica is in Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia; The Birth of Saint Augustine is now in the Courtauld Institute of Art, London; Saint Monica at Prayer with Saint Augustine as a Child is in the Museum Amedeo Lia in La Spezia; Saint Monica Converts her Dying Husband is in the Detroit Institute of Art; Saint Ambrose Baptizes Saint Augustine in the Presence of Saint Monica is in the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

The chapel was moved to the right aisle in the 18th century but the altarpiece did not move with it. The new chapel got new art, and the old was given away to an Augustinian lay community who cut it up and sold it piecemeal. Art historians in the 20th century have traced the scattered components, identifying five panels of the lost altarpiece in museums around the world: The Marriage of St Monica is in Venice’s Gallerie dell’Accademia; The Birth of Saint Augustine is now in the Courtauld Institute of Art, London; Saint Monica at Prayer with Saint Augustine as a Child is in the Museum Amedeo Lia in La Spezia; Saint Monica Converts her Dying Husband is in the Detroit Institute of Art; Saint Ambrose Baptizes Saint Augustine in the Presence of Saint Monica is in the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo.

The panel at the DIA is not on public view. (Well, technically nothing is right now, as the museum is closed. It reopens on July 10th.) Its condition is too delicate for display and requires conservation to keep the wood from splitting more and the prevent continuing paint loss. The DIA has posted a fascinating video about the panel conservation, the first episode of the museum’s new Conservator’s Corner series on its YouTube channel. It covers the recent history of conservation and the latest treatment and is a satisfyingly comprehensive glimpse into how the conservatorial sausage is made.