A 16th century maiolica dish attributed to Nicola da Urbino sold for £1,236,000 ( $1.721 million, including buyer’s premium), which sets a new world record price for maiolica and far exceeds the pre-sale estimate of £80,000-£120,000 ($109,000-$163,000). Bidding was so brisk after opening below the low estimate offers jumped up in £50,000 increments.

A 16th century maiolica dish attributed to Nicola da Urbino sold for £1,236,000 ( $1.721 million, including buyer’s premium), which sets a new world record price for maiolica and far exceeds the pre-sale estimate of £80,000-£120,000 ($109,000-$163,000). Bidding was so brisk after opening below the low estimate offers jumped up in £50,000 increments.

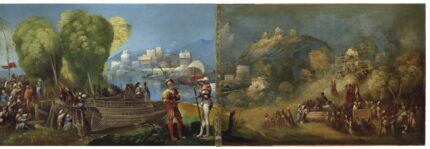

The dish is 11 inches in diameter and is fully painted with a scene from the Biblical account of Samson and Delilah. It’s the moment after Delilah cuts Samson’s hair and armored Philistines capture him. All this is set against a Renaissance architectural background in one-point perspective.

Nicola di Gabriele Sbraghe, called Nicola da Urbino, was a master painter of tin-glazed earthenware (maiolica) active in Urbino between 1520 and his death in 1537/8. His specialty was the “istoriato” (meaning story painting) style in which ceramics were decorated with the same biblical, historical, and mythological subjects popular in Renaissance easel paintings. Plates and bowls were painted with the same sophisticated realism and perspective embraced by Renaissance Old Masters, and often copied or were heavily inspired by specific works. Nicola was so adept at the istoriato style he was dubbed the Raphael of Maiolica Painting.

He worked at the court of Francesco Maria I della Rovere, Duke of Urbino, and his wife Eleonora Gonzaga, who was the eldest child of Francesco II, Marquess of Mantua and his wife the marchioness Isabella d’Este, an influential patron of the arts. Her daughter’s court at Urbino mirrored her mother’s sophistication, and Eleonora was friend and patron to some of the greatest authors, poets and artists of the period. She commissioned an istoriato set from Nicola da Urbino for her mother with scenes from a well-known illustrated edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

It’s not clear who commissioned this plate. It is from his early period, the first of its kind to be sold at auction. It came to the current sellers by descent from Glaswegian merchant and antiquarian James Ewing who traveled in Italy in 1844-5 and bought several important artworks on the trip. His correspondence makes no specific reference to his acquisition of the plate on this trip, but a note in one of his letters to “China pieces of the 14th century” he’d bought in Genoa is believed to have been a less than accurate description of some of the maiolica he acquired in Italy.

It’s not clear who commissioned this plate. It is from his early period, the first of its kind to be sold at auction. It came to the current sellers by descent from Glaswegian merchant and antiquarian James Ewing who traveled in Italy in 1844-5 and bought several important artworks on the trip. His correspondence makes no specific reference to his acquisition of the plate on this trip, but a note in one of his letters to “China pieces of the 14th century” he’d bought in Genoa is believed to have been a less than accurate description of some of the maiolica he acquired in Italy.

The overall blueness, cool flesh tones and creative composition of the piece place it in the early oeuvre of Nicola da Urbino, before 1528. The Old Master print that inspired it is described in Volume XIII (1811) of Adam Bartsch’s compendium of engravings.

[I]t relates to an acclaimed service or credenza encapsulating Nicola’s early poetical style made for an unknown client consisting of seventeen surviving pieces donated to the city of Venice by the patrician Teodoro Correr after his death in 1830. This is the largest surviving set of 16th Century ‘istoriato’ maiolica in the world in a single collection. The service, even quite recently, has been described as “one the loveliest achievements of all maiolica-painting”. There may be reasons on grounds of subject matter and style to speculate that this plate may originally have been part of this service.

In the 19th century the Correr maiolica service was thought by scholars to have been painted by the Urbino painter Timoteo Viti (1469-1523) and was seen as the jewel in the crown of the Correr collection. The painting style of Nicola’s early work that we have here seems to stylistically reference his work in the broadest sense. Viti, trained in the dynamic humanist artistic background of Bologna under Francesco Francia, is known to have worked with Raphael in the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria della Pace in Rome circa 1511. As a friend of Raphael, Viti is reputed to have obtained or inherited the most important group of Raphael’s studio drawings and to have brought them back to Urbino after Raphael’s death. He himself died in 1523. Nicola’s knowledge of Raphael’s style of work may in part be due to links with Viti whose workshop in Urbino he may have frequented or where he may have even trained. Giovanni Antonio da Brescia copied and produced his own versions of the work of the Bolognese printmaker Marcantonio Raimondi (1480-before 1538). Raimondi had also trained under Francesco Francia and did more than anything to disseminate Raphael’s ideas in Italy and abroad from about 1510.

The dish was found unrecorded and unrecognized in a drawer at Lowood House, a country house near Melrose in the Scottish Borders overlooking the River Tweed where the hairs of James Ewing have lived since 1947. It was the meticulous research by specialists at auctioneers Lyon & Turnbull that revealed its identity. This is the first time maiolica from Nicola’s early period to appear for sale on the market.