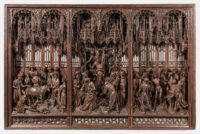

The Saint George Altarpiece, a masterpiece of wood carving by Flemish Renaissance sculptor Jan Borman, has gone back on display at the Art & History Museum in Brussels after three years of meticulous restoration that returned it to its original gory glory.

The Saint George Altarpiece, a masterpiece of wood carving by Flemish Renaissance sculptor Jan Borman, has gone back on display at the Art & History Museum in Brussels after three years of meticulous restoration that returned it to its original gory glory.

The retable is monumental in size at 5 meters (16’5″) wide and 1.6 meters (5’3″) high and features more than 80 figures carved in exquisite detail in a high Gothic architectural setting. It depicts seven scenes from the  martyrdom of Saint George, who according to a 6th century hagiography suffered more than 20 different forms of torture over seven years in an unusually dedicated but nonetheless fruitless attempt to get him to renounce his beliefs. The scenes are dynamically composed, capturing the figures mid-motion: George quartered on a wheeled mechanism, George decapitated, George sawed through the head, George cooked on a brazier, George tied to a pole and flagellated, George roasted in a brazen bull, George hanging upside down over a fire.

martyrdom of Saint George, who according to a 6th century hagiography suffered more than 20 different forms of torture over seven years in an unusually dedicated but nonetheless fruitless attempt to get him to renounce his beliefs. The scenes are dynamically composed, capturing the figures mid-motion: George quartered on a wheeled mechanism, George decapitated, George sawed through the head, George cooked on a brazier, George tied to a pole and flagellated, George roasted in a brazen bull, George hanging upside down over a fire.

The altarpiece was commissioned for the Chapel of Our Lady Outside the Walls at Leuven, founded in 1364 by the Guild of Crossbowmen. In those pre-Reformation times, members of the volunteer municipal militia (think Rembrandt’s Night Watch) had religious requirements as part of the job and often endowed chapels and churches which they then used for solemn ceremonies and to intercede with their patron saints. Saint George was one of them. In Leuven, members swore their oath of allegiance to the guild in the chapel, and they were required to bequeath their coats of arms and crossbows to the chapel after their death.

The altarpiece was commissioned for the Chapel of Our Lady Outside the Walls at Leuven, founded in 1364 by the Guild of Crossbowmen. In those pre-Reformation times, members of the volunteer municipal militia (think Rembrandt’s Night Watch) had religious requirements as part of the job and often endowed chapels and churches which they then used for solemn ceremonies and to intercede with their patron saints. Saint George was one of them. In Leuven, members swore their oath of allegiance to the guild in the chapel, and they were required to bequeath their coats of arms and crossbows to the chapel after their death.

Politics appears to have played an important part in the commissioning of this altarpiece as well. Saint George also happened to the patron saint of Archduke Maximilian of Austria who had recently defeated Flemish rebels and retained control of the Netherlands. The Guild had sided against Maximilian, nearly emptying their coffers over the course of the rebellion. They spent the last of their ready cash commissioning the altarpiece from Jan Borman who was a favored court artist of Maximilian’s. It seems to have done the trick as Maximilian chose not to inflict punitive measures on the Guild.

Politics appears to have played an important part in the commissioning of this altarpiece as well. Saint George also happened to the patron saint of Archduke Maximilian of Austria who had recently defeated Flemish rebels and retained control of the Netherlands. The Guild had sided against Maximilian, nearly emptying their coffers over the course of the rebellion. They spent the last of their ready cash commissioning the altarpiece from Jan Borman who was a favored court artist of Maximilian’s. It seems to have done the trick as Maximilian chose not to inflict punitive measures on the Guild.

The Crossbowmen recovered from the setback. They poured money into their chapel, commissioning exceptionally fine artworks like The Descent from the Cross by Rogier Van der Weyden, now in the Prado Museum http://www.museodelprado.es/en/visit-the-museum/15-masterpieces/work-card/obra/descent-from-the-cross/ because Philip II of Spain demanded it for his palace and bullied the city council of Leuven to sell it to him over the vociferous protests of the Guild of Crossbowmen.

The Crossbowmen recovered from the setback. They poured money into their chapel, commissioning exceptionally fine artworks like The Descent from the Cross by Rogier Van der Weyden, now in the Prado Museum http://www.museodelprado.es/en/visit-the-museum/15-masterpieces/work-card/obra/descent-from-the-cross/ because Philip II of Spain demanded it for his palace and bullied the city council of Leuven to sell it to him over the vociferous protests of the Guild of Crossbowmen.

Alas, that would not be the last the chapel was looted. In 1798 the government of the Batavian Republic, a client state of revolutionary France, abolished all the guilds and Our Lady Outside the Walls was sold. All of the art, all of the silver decorations, the gold leaf, even the copper from the chandeliers was sold off, leaving only an empty husk of a building. It was demolished later that year and private homes built at the site.

Alas, that would not be the last the chapel was looted. In 1798 the government of the Batavian Republic, a client state of revolutionary France, abolished all the guilds and Our Lady Outside the Walls was sold. All of the art, all of the silver decorations, the gold leaf, even the copper from the chandeliers was sold off, leaving only an empty husk of a building. It was demolished later that year and private homes built at the site.

As the only extant signed piece by Borman and the only work of his whose original commission document has survived, the retable would be a unique treasure even if it weren’t widely acknowledged to be his greatest masterpiece. Experts from the museum and the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) took the opportunity to study the work in detail,  dismantling the 48 separate wooden elements. They found hidden surprises. Small parts like fingers and an earring that had fallen off and been trapped under the foreground scenes and one rough hand-carved figure of a praying man. Radiocarbon analysis found that the prayerful man dates to the late 15th century, so researchers believe it may have been a votive that Borman secretly hid in the altarpiece as a prayer for grave.

dismantling the 48 separate wooden elements. They found hidden surprises. Small parts like fingers and an earring that had fallen off and been trapped under the foreground scenes and one rough hand-carved figure of a praying man. Radiocarbon analysis found that the prayerful man dates to the late 15th century, so researchers believe it may have been a votive that Borman secretly hid in the altarpiece as a prayer for grave.

Another surprise was found when the central scene was dismantled: a parchment left behind by one Sohest declaring he had done some restoration work on it in 1835. As the surreptitious addition of a parchment  into the altarpiece might suggest, Sohest didn’t prioritize non-invasive conservation in as close to original condition as possible. The restoration team discovered that the wooden pegs and nails keeping the figures attached did not match the holes. Sohest had dismantled the scenes and put them back together in the wrong order. That inexplicable mistake has now been corrected and the scenes are now in the original order.

into the altarpiece might suggest, Sohest didn’t prioritize non-invasive conservation in as close to original condition as possible. The restoration team discovered that the wooden pegs and nails keeping the figures attached did not match the holes. Sohest had dismantled the scenes and put them back together in the wrong order. That inexplicable mistake has now been corrected and the scenes are now in the original order.

Emmanuelle Mercier, wood sculpture expert (KIK-IRPA): “Careful observation and laboratory analyses revealed that, contrary to tradition, the altarpiece had never been covered with polychromy. That also explains the remarkably fine carving of the wood, which would be lost even under the thinnest layer of paint. Jan II Borman also amazed us with his ability to carve complex scenes, with different figures, from a single block of wood. Tree ring analysis showed that he worked with the hard type of oak found in our regions. All these elements indicate exceptional talent.”

The restorers removed dust and dirt from the countless fine reliefs, glued the pieces of wood that over the years had fallen into the case, and consolidated areas weakened by woodworm. The layers of non-original nineteenth century patina in various shades and the black layer of wax that marred several faces were also thinned down and harmonised. Thus, the plasticity of the contours comes into its own again, and all the fine details are visible.

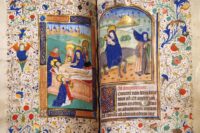

Anne Boleyn’s Book of Hours has joined Isabella Stuart’s in giving up its long-held secrets. Previously unknown inscriptions have been found that identify the close network of owners who kept the book quietly safe, at no inconsiderable risk to themselves, after her execution in 1536.

Anne Boleyn’s Book of Hours has joined Isabella Stuart’s in giving up its long-held secrets. Previously unknown inscriptions have been found that identify the close network of owners who kept the book quietly safe, at no inconsiderable risk to themselves, after her execution in 1536. It is one of only three surviving books of Anne Boleyn’s to have signed inscriptions in her hand. The inscription written across from an image of the Coronation of the Virgin reads: “Remember me when you do pray, that hope dothe led from day to day.” Underneath it is Anne’s signature. Legend has it she carried this book to the gallows.

It is one of only three surviving books of Anne Boleyn’s to have signed inscriptions in her hand. The inscription written across from an image of the Coronation of the Virgin reads: “Remember me when you do pray, that hope dothe led from day to day.” Underneath it is Anne’s signature. Legend has it she carried this book to the gallows.Kate’s research uncovered that the book was passed from female to female, of families not only local to the Boleyn family at Hever but also connected by kin.