A Paris auction of original Tintin art by Belgian creator Hergé and memorabilia has taken in almost $1.4 million (1.09 million euros). The May 29th sale at the Drouot-Montaigne auction house offered 230 Tintin-themed pieces from 70 collectors, some of which even Moulinsart, Hergé’s foundation and a partner in the sale, had no idea existed.

A Paris auction of original Tintin art by Belgian creator Hergé and memorabilia has taken in almost $1.4 million (1.09 million euros). The May 29th sale at the Drouot-Montaigne auction house offered 230 Tintin-themed pieces from 70 collectors, some of which even Moulinsart, Hergé’s foundation and a partner in the sale, had no idea existed.

The most expensive lot was an original inked and water-painted two-page spread from “King Ottokar’s Sceptre”, which sold for 243,750 euros ($299,620), 43,750 euros above its top estimate. It was bought by a Belgian collector, as were many of the items on sale.

An extremely rare life-size bronze statue of Tintin and Snowy by artist Nat Neujean sold for 125,000 euros ($153,650), well within the estimate price range but a world record for a Neujean piece. There are only four other copies of this statue in the world. It’s going to live in Belgium too, although it was purchased by a French gallery owner. He’s going to put it on display in his gallery in Brussels. Prediction: he’s going to get a lot more Belgian visitors to his gallery from now on.

One of the most unique items on sale was an original Hergé gouache called “Tintin and the Sea Shells” that he made in 1947 as a birthday present for a friend of his who had a large sea shell collection. It shows Tintin, Captain Haddock and Snowy wandering on a beach littered with huge sea shells. Professor Calculus and walks behind them holding his trusty pendulum while looking at the ocean. It’s surreal and whimsical and generally awesome. The piece was priced at 70,000 euros but sold for almost twice that, 131,250 euros ($160,800).

One of the most unique items on sale was an original Hergé gouache called “Tintin and the Sea Shells” that he made in 1947 as a birthday present for a friend of his who had a large sea shell collection. It shows Tintin, Captain Haddock and Snowy wandering on a beach littered with huge sea shells. Professor Calculus and walks behind them holding his trusty pendulum while looking at the ocean. It’s surreal and whimsical and generally awesome. The piece was priced at 70,000 euros but sold for almost twice that, 131,250 euros ($160,800).

There were also a variety of more affordable items on the block, including original lithographs and panels priced at 2,000 – 3,000 euros, plus personal belongings of Hergé’s, like scarves, paperweights and colored pencil boxes.

It’s not all happy sea shells and wads of cash in Tintinland, however. Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo, a Congolese man who lives in Brussels, is suing Moulinsart and Tintin comic book publishers Casterman to get “Tintin in the Congo” taken off the shelves in Belgium and France.

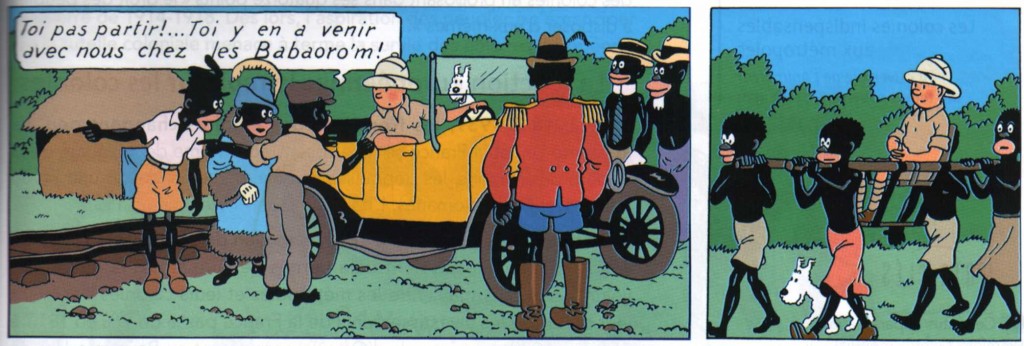

The book is hugely racist, of course, packed with offensive caricatures of Africans, and particularly offensive to the Congolese given the ugly history of Belgian colonialism which became a poster child for the most brutal, bloody European exploitation of African people and resources. When Hergé wrote the book in 1931, the Congo was still a Belgian colony and would remain one for 3 decades or so.

From a Time magazine article on the lawsuit:

Hergé, who had never visited Congo, was just 23 when he wrote the book, which he was persuaded to do as part of a government-led initiative to encourage Belgians to take up commissions in Congo. But Mbutu Mondondo says it served — and still serves — to prop up a sanitized account of Belgium’s colonialism. “It twists history to suggest that everything was happy and fun,” he says. “In reality, it was a tragic, hurtful time.”

Belgian Congo was one of the most bloody and cruel colonial regimes in Africa. The original inspiration for Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, it was claimed for King Leopold II in 1885 by the explorer Henry Morton Stanley. For 23 years, the area — the size of France, Germany, Norway, Spain and Sweden combined — was the King’s personal possession. Leopold’s agents pioneered a ruthless forced-labor system for gathering wild rubber: villages that failed to meet the rubber-collection quotas were required to pay the remaining amount in amputated hands. Some estimates say Congo’s population fell by 10 million during that time.

Mondondo has already pressed criminal charges, but the case has been winding its way through the courts for 3 years, so last month he upped the ante and filed the civil suit. Moulinsart’s lawyer Alain Berenboom considers the legal case the equivalent of book burning.

Fair enough, but Berenboom also denies that “Tintin in the Congo” is racist at all. “It has never caused public order problems, including in Africa” he says, as if racism were defined by “public order problems” the images cause. Even Hergé himself acknowledged that he had depicted a naive fantasy of Belgian colonialism in the comic. Later in life he would refer to the book as “the sin of his youth.”