A 19-by-20-foot stage curtain painted by Pablo Picasso in 1919 that now hangs in the Four Seasons Restaurant (no relation to the hotel) is in danger. RFR Holding, owners of the historic Seagram Building since 2000, want to take the painting down, ostensibly because the travertine wall it hangs on has suffered structural damage, but only their engineers think the wall is structurally unsound and removing the fragile curtain is far more likely to damage it than errant stone facing becoming unmoored and tearing through the fabric.

A 19-by-20-foot stage curtain painted by Pablo Picasso in 1919 that now hangs in the Four Seasons Restaurant (no relation to the hotel) is in danger. RFR Holding, owners of the historic Seagram Building since 2000, want to take the painting down, ostensibly because the travertine wall it hangs on has suffered structural damage, but only their engineers think the wall is structurally unsound and removing the fragile curtain is far more likely to damage it than errant stone facing becoming unmoored and tearing through the fabric.

The Picasso curtain was a front cloth for a production of Le Tricorne by the Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev which premiered on July 22nd, 1919, at London’s Alhambra Theatre. Based on a novella by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón and with music by Manuel de Falla, the ballet tells the story of a miller and his wife who get playful revenge on the lecherous governor who hit on the wife and tried to have the miller arrested. Falla had written El corregidor y la molinera, a two-scene pantomime of the novella, during World War I. It was a popular and critical success. Diaghilev and Ballets Russes dancer/choreographer Léonide Massine saw the show in Madrid in May of 1917 and felt it could be developed into a full-length Spanish ballet.

The Ballets Russes began their second season of performances in Spain in June. During the season, Falla took Massine and Diaghilev to see the best flamenco dancers in the city. That summer most of the troupe toured South America while Massine and Diaghilev traveled around Spain, absorbing the music and dance and working together on Le Tricorne. Pablo Picasso, who had already collaborated with the Ballets Russes on the ballet Parade, music by Erik Satie, scenario by Jean Cocteau, in 1916-7, worked with them on the Spanish ballet. One of the Ballets Russes dancers, Olga Khokhlova, quit before the troupe went to South America and traveled to Barcelona with Picasso. Within a year Picasso and Khokhlova would be married.

The Ballets Russes began their second season of performances in Spain in June. During the season, Falla took Massine and Diaghilev to see the best flamenco dancers in the city. That summer most of the troupe toured South America while Massine and Diaghilev traveled around Spain, absorbing the music and dance and working together on Le Tricorne. Pablo Picasso, who had already collaborated with the Ballets Russes on the ballet Parade, music by Erik Satie, scenario by Jean Cocteau, in 1916-7, worked with them on the Spanish ballet. One of the Ballets Russes dancers, Olga Khokhlova, quit before the troupe went to South America and traveled to Barcelona with Picasso. Within a year Picasso and Khokhlova would be married.

During their time in Spain, Léonide Massine hired Félix Fernández García, a flamenco dancer from Seville, to teach him the footwork. Fernández García expected to dance the lead in the production and indeed traveled with the troupe to London, but he found out from the advertising posters that Massine would be dancing the part of the Miller. His reaction to the bad news was to start carrying a ticking metronome with him everywhere he went. When one night he was found dancing naked on the altar of the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields in Trafalgar Square, Fernández García was committed to Long Grove Hospital for insanity. He would remain institutionalized at Long Grove until his death in 1941. In a creepy twist, after his institutionalization Diaghilev had García declared dead in Spain in 1919.

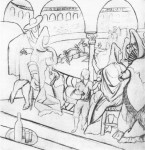

Picasso joined the troupe in London to finish his work on the sets and costumes. He made the drop curtain in a paint studio on Floral Street, Covent Garden, over the course of three weeks. The curtain hung in front of the stage during the overture the first major number after which it was raised to reveal the set pieces. In keeping with the ballet’s focus on Spanish culture, Picasso chose to depict a scene at a bullfighting ring even though there is no bullfight in the story.

Picasso joined the troupe in London to finish his work on the sets and costumes. He made the drop curtain in a paint studio on Floral Street, Covent Garden, over the course of three weeks. The curtain hung in front of the stage during the overture the first major number after which it was raised to reveal the set pieces. In keeping with the ballet’s focus on Spanish culture, Picasso chose to depict a scene at a bullfighting ring even though there is no bullfight in the story.

Diaghilev kept the curtain after the show was over. Less than a decade later in 1928. he cut off the marbleized paper edges and sold the painted center to Swiss collector G. F. Reber. In 1957 it was purchased for $50,000 by Phyllis Lambert, daughter of Seagram owner Samuel Bronfman. When her father asked to help decorate the Seagram Building, she and architect Philip Johnson chose the dramatic Le Tricorne for what would become known as Picasso Alley, the hallway connecting the Four Seasons’ two dining rooms, the pool room and the grill room.

In 2005, the painting was donated to the New York Landmarks Conservancy by Vivendi Universal, then owners of the Seagram company, on the condition that the curtain remain in situ at the Four Seasons. The Seagram Building and the Four Seasons restaurant were given landmark status in 1989, but because in theory the Picasso curtain is moveable, it isn’t covered by landmark protections. This became an acute problem in November of 2013 when the Landmarks Conservancy got a call from Aby Rosen, co-founder of RFR, claiming there was a steam leak in the wall and they’d have to take down the painting to repair it. When asked for the engineer’s report, Rosen replied there was none.

In 2005, the painting was donated to the New York Landmarks Conservancy by Vivendi Universal, then owners of the Seagram company, on the condition that the curtain remain in situ at the Four Seasons. The Seagram Building and the Four Seasons restaurant were given landmark status in 1989, but because in theory the Picasso curtain is moveable, it isn’t covered by landmark protections. This became an acute problem in November of 2013 when the Landmarks Conservancy got a call from Aby Rosen, co-founder of RFR, claiming there was a steam leak in the wall and they’d have to take down the painting to repair it. When asked for the engineer’s report, Rosen replied there was none.

Next the Landmarks Conservancy received a letter from RFR on December 20th telling them work on the wall would begin the first week in January. This time there was an engineer’s report — no mention of a steam leak, just of the tiles moving a half-inch indicating structural issues — but when the LC sent their experts to assess the soundness of the wall, their findings were significantly different. Although they also found some tiles had moved, the amount of the movement was much less and fewer tiles were affected.

Finally a plan was in place to take down the curtain at 3:00 AM on February 9th so as not to disturb diners at the Four Seasons. The Conservancy rushed to court to get a temporary restraining order blocking the move which according to RFR’s lawyer involved rolling the fragile canvas up “one click at a time” and putting it in a rented van. Even the art mover admitted the curtain might “crack like a potato chip” in the process. Less than two days before the planned move, the court issued the restraining order.

Finally a plan was in place to take down the curtain at 3:00 AM on February 9th so as not to disturb diners at the Four Seasons. The Conservancy rushed to court to get a temporary restraining order blocking the move which according to RFR’s lawyer involved rolling the fragile canvas up “one click at a time” and putting it in a rented van. Even the art mover admitted the curtain might “crack like a potato chip” in the process. Less than two days before the planned move, the court issued the restraining order.

The owners of the Seagram Building stunned the judge by arguing they can just replace the famed artist’s work if anything happened to it.

“If we break it, we buy it,” lawyer Andrew Kratenstein told Justice Matthew Cooper’s clerk outside the courtroom.

There aren’t enough eyes to roll over that one. The curtain is obviously not replaceable being a unique work by a dead master. That they would even attempt such an argument underscores that they really don’t care what happens to the painting. Rosen was heard referring to the curtain as a “schmatte,” meaning “rag” in Yiddish. The engineering claims are barely believable, so what seems to be going on here is that Rosen wants to put some of the art he likes — he’s an avid collector of works by artists like Jeff Coons and Damien Hirst — in the space currently occupied by the largest Picasso in the country.

The restraining order is still in place, having been extended several times. The Conservancy has asked for an injunction preventing the removal of the curtain. The court will hear arguments from experts on April 30th and May 1st, after which Judge Carol Edmead will rule on the request. They’re buying time, basically. The larger legal question of whether the Conservancy can stop the owners of the building from doing whatever they want to their property is a thornier problem.