Last October, archaeologists surveying the site of planned road work on federal highway 189 in Groß Pankow, Brandenburg, Germany, unearthed human remains. They had already found some Bronze Age materials on the site — fragments of pottery, a stone axe — from the 1st millennium B.C., but nothing of great note. The rounded grave pit at first glance looked much like the pits from the Bronze Age settlement, but the skeletal remains, on the other hand, were immediately arresting. The bones were oddly positioned, the arms angled sideways up to the neck, the thigh bones turned backwards. They were also brutally broken, all the long bones shattered with many pieces missing.

Last October, archaeologists surveying the site of planned road work on federal highway 189 in Groß Pankow, Brandenburg, Germany, unearthed human remains. They had already found some Bronze Age materials on the site — fragments of pottery, a stone axe — from the 1st millennium B.C., but nothing of great note. The rounded grave pit at first glance looked much like the pits from the Bronze Age settlement, but the skeletal remains, on the other hand, were immediately arresting. The bones were oddly positioned, the arms angled sideways up to the neck, the thigh bones turned backwards. They were also brutally broken, all the long bones shattered with many pieces missing.

It was clear the person had died far more recently than 1,000 B.C. An iron belt buckle found in the grave provided a general date of between the 15th and 17th centuries. Further examination revealed the deceased was a man in his mid to late 30s who had been executed on the wheel. His bones are in more than a thousand pieces. This is the first time a skeleton of someone broken on the wheel has been found in Germany, even though judicial execution by wheel was employed in the Holy Roman Empire from the Middle Ages to the 19th century.

It was clear the person had died far more recently than 1,000 B.C. An iron belt buckle found in the grave provided a general date of between the 15th and 17th centuries. Further examination revealed the deceased was a man in his mid to late 30s who had been executed on the wheel. His bones are in more than a thousand pieces. This is the first time a skeleton of someone broken on the wheel has been found in Germany, even though judicial execution by wheel was employed in the Holy Roman Empire from the Middle Ages to the 19th century.

This is not a coincidence. The whole point of the wheel was to display the broken bodies until they rotted away entirely, leaving the bones for carrion birds to enjoy. The punishment was reserved for the worst criminals — serial killers, murderers who killed someone during the commission of another crime, killers of kin — and the destruction of the body in a slow, public fashion did double-duty as the most gruesome retribution and as a stern warning to the public.

This is not a coincidence. The whole point of the wheel was to display the broken bodies until they rotted away entirely, leaving the bones for carrion birds to enjoy. The punishment was reserved for the worst criminals — serial killers, murderers who killed someone during the commission of another crime, killers of kin — and the destruction of the body in a slow, public fashion did double-duty as the most gruesome retribution and as a stern warning to the public.

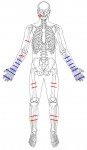

Death by wheel was usually a two-stage process. First a large spoked wagon wheel would be slammed onto the large bones of the arms and legs, breaking them in two places each. Then the wheel would strike the spine, breaking it. With the body’s skeletal structure in pieces, the condemned was then tied to the wheel, his limbs woven in and out of the spokes. Finally the wheel was raised on a pike and planted into the ground. If the man wasn’t dead yet, and he usually wasn’t unless he was fortunate enough to have been deliberately struck with fatal blows to the chest and abdomen as an act of mercy, he would die in slow unspeakable agony over the course of hours, often days.

Death by wheel was usually a two-stage process. First a large spoked wagon wheel would be slammed onto the large bones of the arms and legs, breaking them in two places each. Then the wheel would strike the spine, breaking it. With the body’s skeletal structure in pieces, the condemned was then tied to the wheel, his limbs woven in and out of the spokes. Finally the wheel was raised on a pike and planted into the ground. If the man wasn’t dead yet, and he usually wasn’t unless he was fortunate enough to have been deliberately struck with fatal blows to the chest and abdomen as an act of mercy, he would die in slow unspeakable agony over the course of hours, often days.

In the dead of Groß Pankow for the first time the torture could be accurately documented: A big blow for example, had torn away half his face, as can be seen on the damaged skull.

This could mean that the offender previously received the fatal coup de grace by the executioner. However, this happened rarely. More often the delinquent – before he was dead – fell off the wheel. This was then as God’s judgment, the delinquent was then free.

Obviously that’s not what happened here. He died in a horrific fashion. Why this wheeled man had his bones collected and respectfully buried, we do not know. The place where he was found was an old military road. It could have been a place used for a mobile execution rather than a permanent gallows or regular killing zone. With no police presence, a family member of the deceased or just someone with an ounce of compassion could have removed the broken body and buried it.

Obviously that’s not what happened here. He died in a horrific fashion. Why this wheeled man had his bones collected and respectfully buried, we do not know. The place where he was found was an old military road. It could have been a place used for a mobile execution rather than a permanent gallows or regular killing zone. With no police presence, a family member of the deceased or just someone with an ounce of compassion could have removed the broken body and buried it.