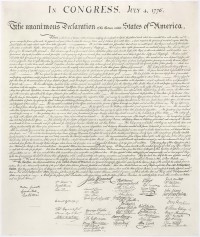

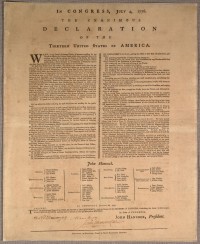

The official transcript of the Declaration of Independence puts a period after the iconic phrase “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The transcript is drawn from an 1823 engraving by printer William J. Stone who was commissioned by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to make a facsimile of the original manuscript on parchment written by Timothy Matlack, clerk to the secretary of the Second Continental Congress, and signed by the Continental Congress on August 2nd, 1776. (July 4th is the day the Declaration was officially adopted, not the day John Hancock put his John Hancock on it.) The Stone engraving is the most frequently reproduced version of the Declaration of Independence.

The official transcript of the Declaration of Independence puts a period after the iconic phrase “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The transcript is drawn from an 1823 engraving by printer William J. Stone who was commissioned by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to make a facsimile of the original manuscript on parchment written by Timothy Matlack, clerk to the secretary of the Second Continental Congress, and signed by the Continental Congress on August 2nd, 1776. (July 4th is the day the Declaration was officially adopted, not the day John Hancock put his John Hancock on it.) The Stone engraving is the most frequently reproduced version of the Declaration of Independence.

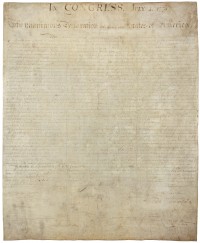

By the time Stone made his copy, the original was already suffering from condition issues. That’s why he was commissioned to copy it, in fact, so there would be a version for distribution to the surviving signers, their families, luminaries of the Revolution like Lafayette and public institutions nationwide. Stone’s engraving is considered the closest thing we have to the Declaration when it was still legible. The original, now on display in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., is kept in a bulletproof glass case filled with inert argon gas. The writing is so faded as to be next to illegible.

By the time Stone made his copy, the original was already suffering from condition issues. That’s why he was commissioned to copy it, in fact, so there would be a version for distribution to the surviving signers, their families, luminaries of the Revolution like Lafayette and public institutions nationwide. Stone’s engraving is considered the closest thing we have to the Declaration when it was still legible. The original, now on display in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., is kept in a bulletproof glass case filled with inert argon gas. The writing is so faded as to be next to illegible.

It’s impossible to confirm with the naked eye, therefore, whether there was a period after “the pursuit of Happiness” in the original. Professor Danielle Allen from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, thinks there was not, that Stone made a mistake that has been carried forward nearly two centuries. It’s not pedantry that underpins her analysis. The punctuation plays a significant part in the interpretation of the preamble.

The period creates the impression that the list of self-evident truths ends with the right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” she says. But as intended by Thomas Jefferson, she argues, what comes next is just as important: the essential role of governments — “instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” — in securing those rights.

“The logic of the sentence moves from the value of individual rights to the importance of government as a tool for protecting those rights,” Ms. Allen said. “You lose that connection when the period gets added.”

Correcting the punctuation, if indeed it is wrong, is unlikely to quell the never-ending debates about the deeper meaning of the Declaration of Independence. But scholars who have reviewed Ms. Allen’s research say she has raised a serious question.

“Are the parts about the importance of government part of one cumulative argument, or — as Americans have tended to read the document — subordinate to ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’?” said Jack Rakove, a historian at Stanford and a member of the National Archives’ Founding Fathers Advisory Committee. “You could make the argument without the punctuation, but clarifying it would help.”

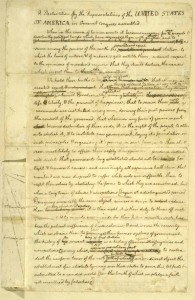

Several early documents support Allen’s argument. There is no period in any of the official versions written or printed in 1776. Thomas Jefferson’s original rough draft has a semicolon after the pursuit of Happiness, just as it does at the end of all the “that” clauses in the sentence. The Dunlap Broadside, printed in Philadelphia on July 4th, 1776, uses a triplicate dash, an m-dash followed by a space and a hyphen.

Several early documents support Allen’s argument. There is no period in any of the official versions written or printed in 1776. Thomas Jefferson’s original rough draft has a semicolon after the pursuit of Happiness, just as it does at the end of all the “that” clauses in the sentence. The Dunlap Broadside, printed in Philadelphia on July 4th, 1776, uses a triplicate dash, an m-dash followed by a space and a hyphen.

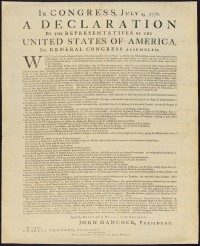

There is a period in an unauthorized leaked version of the Declaration published in Benjamin Towne’s newspaper, the Pennsylvania Evening Post, on July 6, 1776. The first official document to include a period after Happiness was the 1777 broadside printed by Mary Katharine Goddard. The first public issue of the  Declaration to include the names of all the signatories (minus one, Thomas McKean of Delaware, who may have signed after Goddard’s version was printed), the Goddard broadside was commissioned by Congress for distribution to the states. Goddard and Towne knew each other well. Towne began his career in the print shop of William Goddard, Mary’s father, and Mary had reprinted Towne’s version in her own paper, the Baltimore Journal, on July 10th, 1776. It’s no surprise, therefore, that she stuck with Towne’s punctuation when she printed the official broadside in January of 1777.

Declaration to include the names of all the signatories (minus one, Thomas McKean of Delaware, who may have signed after Goddard’s version was printed), the Goddard broadside was commissioned by Congress for distribution to the states. Goddard and Towne knew each other well. Towne began his career in the print shop of William Goddard, Mary’s father, and Mary had reprinted Towne’s version in her own paper, the Baltimore Journal, on July 10th, 1776. It’s no surprise, therefore, that she stuck with Towne’s punctuation when she printed the official broadside in January of 1777.

Allen thinks the period made its way into Towne’s bootleg printing as an artifact of the many diacritical marks Jefferson included in his drafts to convey the flow of it as a document to be read out loud. You can read her paper about it, Punctuating Happiness, here (pdf). She goes into very persuasive and fascinating detail, analyzing the early written and print versions, breaking down the stylistic differences between John Adams’ work and Thomas Jefferson’s and ever so much more. It is seriously a page-turner and very appropriate reading for the day.

Allen thinks the period made its way into Towne’s bootleg printing as an artifact of the many diacritical marks Jefferson included in his drafts to convey the flow of it as a document to be read out loud. You can read her paper about it, Punctuating Happiness, here (pdf). She goes into very persuasive and fascinating detail, analyzing the early written and print versions, breaking down the stylistic differences between John Adams’ work and Thomas Jefferson’s and ever so much more. It is seriously a page-turner and very appropriate reading for the day.

The National Archives found it persuasive as well. They are now looking into making some changes to their online presentation of the Declaration based on her work, and are examining the possibility of deploying new imaging technology to photograph the Declaration through its encasement and reveal details not visible to the naked eye.