One of only four known original World War I recruitment posters featuring the iconic image of Lord Kitchener pointing at the viewer sold at auction on Wednesday for £22,000 ($37,656), double the low estimate of £10,000 – £15,000. The other three are in museums, one in the Imperial War Museum in London, one in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, and one in the Museum of Brands, Packaging & Advertising in London (the display wing of the massive Robert Opie Collection). They’re not likely to come up for sale, well, ever, so this was a unique opportunity.

One of only four known original World War I recruitment posters featuring the iconic image of Lord Kitchener pointing at the viewer sold at auction on Wednesday for £22,000 ($37,656), double the low estimate of £10,000 – £15,000. The other three are in museums, one in the Imperial War Museum in London, one in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, and one in the Museum of Brands, Packaging & Advertising in London (the display wing of the massive Robert Opie Collection). They’re not likely to come up for sale, well, ever, so this was a unique opportunity.

The poster was part of a remarkable collection of almost 200 World War I posters that spent decades out of the light in an attic in Kent. The sellers inherited the collection from their grandfather, who had helped distribute surplus posters to libraries, museums and collectors on behalf of His Majesty’s Stationary Office at the end of the war. The grandfather died some years back, but the sellers didn’t realize what an absolute treasure they had until they gave the collection a good, hard look inspired by all the discussion and activities around the hundredth anniversary of the start of the war. They had a complete collection of all posters published by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee between 1914 and 1916 (when conscription rendered recruitment moot), plus additional ephemera.

The poster was part of a remarkable collection of almost 200 World War I posters that spent decades out of the light in an attic in Kent. The sellers inherited the collection from their grandfather, who had helped distribute surplus posters to libraries, museums and collectors on behalf of His Majesty’s Stationary Office at the end of the war. The grandfather died some years back, but the sellers didn’t realize what an absolute treasure they had until they gave the collection a good, hard look inspired by all the discussion and activities around the hundredth anniversary of the start of the war. They had a complete collection of all posters published by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee between 1914 and 1916 (when conscription rendered recruitment moot), plus additional ephemera.

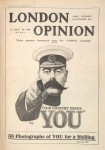

The Kitchener poster is one of the latter. It wasn’t an official publication of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, but rather a recruitment message privately issued by the popular magazine London Opinion. London Opinion had a circulation of about 250,000 a week at this time and was swept up in the patriotic fervor that characterized the weeks after Britain declared war on Germany on August 4th, 1914. The magazine commissioned illustrator and cartoon artist Alfred Leete to create a recruitment-themed cover for its September 5th issue. He scared it up in less than a day.

The Kitchener poster is one of the latter. It wasn’t an official publication of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, but rather a recruitment message privately issued by the popular magazine London Opinion. London Opinion had a circulation of about 250,000 a week at this time and was swept up in the patriotic fervor that characterized the weeks after Britain declared war on Germany on August 4th, 1914. The magazine commissioned illustrator and cartoon artist Alfred Leete to create a recruitment-themed cover for its September 5th issue. He scared it up in less than a day.

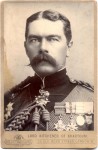

It was not a complex design. Leete used a photograph of Lord Kitchener, probably the one shot by famed portrait photographer Alexander Bassano around 1885 which had become very well known in postcard form, and modified it so that both his eyes stared forward (Kitchener had a pronounced strabismus in one eye), his jawline was more heroically square, and his moustache larger and more dramatically shaped. He added the uniform hat and the foreshortened arm and finger pointing at the viewer, a design that had been used before in a 1906 cigarette ad, among others. Under Kitchener’s neck were the words “Your country needs YOU,” while magazine promotions above and below offered recruits £1,000 worth of insurance and 50 photographs for a shilling.

It was not a complex design. Leete used a photograph of Lord Kitchener, probably the one shot by famed portrait photographer Alexander Bassano around 1885 which had become very well known in postcard form, and modified it so that both his eyes stared forward (Kitchener had a pronounced strabismus in one eye), his jawline was more heroically square, and his moustache larger and more dramatically shaped. He added the uniform hat and the foreshortened arm and finger pointing at the viewer, a design that had been used before in a 1906 cigarette ad, among others. Under Kitchener’s neck were the words “Your country needs YOU,” while magazine promotions above and below offered recruits £1,000 worth of insurance and 50 photographs for a shilling.

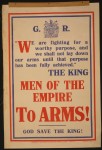

The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, meanwhile, was still using text-only recruiting pitches in periodicals and on posters. These were scions of the upper classes who had no high opinion of commercial advertising and its eye-catching gimmicks. A royal coat of arms was acceptable, but the first poster with an actual image on it had a simple silhouette of the United Kingdom behind the legend “Britons! Your country needs you.” Kitchener himself had no interest in being on posters.

The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, meanwhile, was still using text-only recruiting pitches in periodicals and on posters. These were scions of the upper classes who had no high opinion of commercial advertising and its eye-catching gimmicks. A royal coat of arms was acceptable, but the first poster with an actual image on it had a simple silhouette of the United Kingdom behind the legend “Britons! Your country needs you.” Kitchener himself had no interest in being on posters.

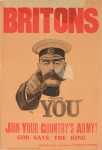

So the London Opinion took it upon themselves to put him on one. Unlike the magazine cover, the poster version had some color. “BRITONS,” it blared in large bold red letters above the famous image of the Secretary of State for War, Kitchener “Wants YOU. Join your country’s army! God save the King.” It was printed in September of 1914 in a relatively modest run of about 10,000 units. Since it was not an official poster, it wasn’t on display in military recruitment offices and other common PRC outlets, but it still got around, distributed along with magazines at newstands, at train stations and even on a Belfast tram dedicated to recruitment posters.

So the London Opinion took it upon themselves to put him on one. Unlike the magazine cover, the poster version had some color. “BRITONS,” it blared in large bold red letters above the famous image of the Secretary of State for War, Kitchener “Wants YOU. Join your country’s army! God save the King.” It was printed in September of 1914 in a relatively modest run of about 10,000 units. Since it was not an official poster, it wasn’t on display in military recruitment offices and other common PRC outlets, but it still got around, distributed along with magazines at newstands, at train stations and even on a Belfast tram dedicated to recruitment posters.

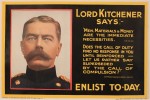

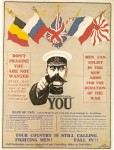

Kitchener’s basilisk stare and engorged index finger made an impression. By 1915, there were versions of Leete’s designs on posters in Canada and New Zealand, and other countries soon followed. The PRC issued their own Kitchener poster in 1915. He wasn’t pointing or hollering in all caps — the rallying cry was a 30-word quote from a speech — but the face was similar to Leete’s drawing of the youthful 1885 Kitchener. Later that year the PRC finally issued an official poster featuring Leete’s design. There were combatant flags at the top and walls of text on the sides and bottom, but there was Lord Kitchener pointing sternly, informing viewers that “Your country needs YOU.”

Kitchener’s basilisk stare and engorged index finger made an impression. By 1915, there were versions of Leete’s designs on posters in Canada and New Zealand, and other countries soon followed. The PRC issued their own Kitchener poster in 1915. He wasn’t pointing or hollering in all caps — the rallying cry was a 30-word quote from a speech — but the face was similar to Leete’s drawing of the youthful 1885 Kitchener. Later that year the PRC finally issued an official poster featuring Leete’s design. There were combatant flags at the top and walls of text on the sides and bottom, but there was Lord Kitchener pointing sternly, informing viewers that “Your country needs YOU.”

The year after that, Leete’s vision was transformed into another iconic image. On July 6th, 1916, the cover of the illustrated news magazine Leslie’s Weekly was a drawing by James Montgomery Flagg of a stern Uncle Sam pointing at the viewer, asking them “What Are You Doing for Preparedness?” This was almost a year before the United States’ entry into the war, but advocates for intervention on the British side like former President Theodore Roosevelt and former Secretary of War Elihu Root had been campaigning for a massive boost of military funding and troop training (not just of the regular army but of hundreds of thousands of conscripts as well) so the country would be prepared for war when it came.

The year after that, Leete’s vision was transformed into another iconic image. On July 6th, 1916, the cover of the illustrated news magazine Leslie’s Weekly was a drawing by James Montgomery Flagg of a stern Uncle Sam pointing at the viewer, asking them “What Are You Doing for Preparedness?” This was almost a year before the United States’ entry into the war, but advocates for intervention on the British side like former President Theodore Roosevelt and former Secretary of War Elihu Root had been campaigning for a massive boost of military funding and troop training (not just of the regular army but of hundreds of thousands of conscripts as well) so the country would be prepared for war when it came.

The Preparedness Movement got its way with the National Defense Act of 1916, passed in June 1916, and the hawkishly patriotic Leslie’s Weekly was fully on board. The Flagg cover became a full-on recruitment poster the next year after the United States declared war on Germany on April 6th, 1917. It was a massive success with more than four million printed in 1917 and 1918. Flagg himself modestly declared it “the most famous poster in the world,” but even if that’s true, Alfred Leete and Lord Kitchener deserve a large portion of the credit.

The Preparedness Movement got its way with the National Defense Act of 1916, passed in June 1916, and the hawkishly patriotic Leslie’s Weekly was fully on board. The Flagg cover became a full-on recruitment poster the next year after the United States declared war on Germany on April 6th, 1917. It was a massive success with more than four million printed in 1917 and 1918. Flagg himself modestly declared it “the most famous poster in the world,” but even if that’s true, Alfred Leete and Lord Kitchener deserve a large portion of the credit.