A recent study has found that a skeleton unearthed on the Scottish island of Tiree a century ago is the UK’s oldest case of rickets.

In spring of 1912, A. Henderson Bishop, a wealthy pig-breeder and amateur archaeologist, led a small team of antiquaries to excavate an area near the town of Balevullin on the northeastern part of the island where artifacts and architectural remains had been exposed by wind erosion. They focused their attentions on an early Iron Age structure and its environs, collecting artifacts like flints and hammer-stones from the sandy soil. While gathering surface artifacts, they came across a flat stone pile under which they found skeletal human remains. A little digging turned up another three inhumations.

In spring of 1912, A. Henderson Bishop, a wealthy pig-breeder and amateur archaeologist, led a small team of antiquaries to excavate an area near the town of Balevullin on the northeastern part of the island where artifacts and architectural remains had been exposed by wind erosion. They focused their attentions on an early Iron Age structure and its environs, collecting artifacts like flints and hammer-stones from the sandy soil. While gathering surface artifacts, they came across a flat stone pile under which they found skeletal human remains. A little digging turned up another three inhumations.

The islanders heard about the finds and protested that the team was digging up their ancestors to ship them to a London museum. They reported their suspicions to the Duke of Argyle who told Bishop and his team to leave Tiree without taking anything with them. Hoping for a reprieve, they showed their modest artifacts to the local Factor (estate manager) who allowed them to take their finds, including the first skeleton, off the island. It would up in the University of Glasgow’s Hunterian collection.

Because the inhumations were found near the Iron Age structure, the skeleton was classified as Iron Age. This misclassification proved to be the reason why it has now been properly classified. A recent accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating project by University of Bradford and University of Durham researchers sought to date human remains found at Iron Age sites in Scotland. When the Balevullin skeleton was tested, it was found to be much older, dating to between 3340 and 3090 B.C., late Stone Age, not Iron Age.

Because the inhumations were found near the Iron Age structure, the skeleton was classified as Iron Age. This misclassification proved to be the reason why it has now been properly classified. A recent accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating project by University of Bradford and University of Durham researchers sought to date human remains found at Iron Age sites in Scotland. When the Balevullin skeleton was tested, it was found to be much older, dating to between 3340 and 3090 B.C., late Stone Age, not Iron Age.

The result took everyone by surprise, firstly because it was clear from a visual examination of the bones that this individual had suffered from rickets, a disease usually (but not always) associated with the endemic malnutrition and gloom of early modern slums rather than the fresh outdoorsy life of the Neolithic Inner Hebrides. It was also unexpected because while Britain is replete with Neolithic funerary structures — mainly monumental chambered cairns — with individual inhumations, monumentless inhumation cemeteries are extremely rare. Only one other flat inhumation cemetery in known in Britain: two adults and a child buried at Barrow Hills in Oxfordshire.

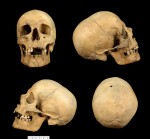

The Balevullin skeleton is 68% complete which allowed researchers to determine the individual was likely a woman. She was around 25-30 years old and between 4’9″ and 4’11” tall, very petite even by the standards of Neolithic Britain. Her sternum is severely deformed with a condition known as pigeon chest. The ribs exhibit associated deformations, as do the humerus bones whose shafts are bowed and rotated. The one surviving femur is also deformed although less so than the other bones.

The Balevullin skeleton is 68% complete which allowed researchers to determine the individual was likely a woman. She was around 25-30 years old and between 4’9″ and 4’11” tall, very petite even by the standards of Neolithic Britain. Her sternum is severely deformed with a condition known as pigeon chest. The ribs exhibit associated deformations, as do the humerus bones whose shafts are bowed and rotated. The one surviving femur is also deformed although less so than the other bones.

All of these bone deformations are classic signs of vitamin D deficiency. Some of them point to rickets during infancy, and all of them are typical of childhood rickets. Evidence of bone repair suggest she suffered repeated periods of vitamin D deficiency in early and later childhood. This was confirmed by stable isotope analysis.

Strontium, oxygen, nitrogen and carbon isotope analyses performed on a tooth and rib revealed that the individual grew up in the Northern or Western Isles of Britain, so was probably a local Tiree girl. Her diet was based primarily on terrestrial plants and proteins with very little in the way of marine vegetables and fish. As weird as that seems, it is consistent with other Neolithic remains from farming communities on the western seaboard (and with medieval Viking settlers in Greenland). It seems the island life in the Neolithic era did not involve eating much of the abundant fish and seaweed all around them. The levels of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the layers of dentine in the tooth indicated a major dietary or physiological stress between the ages of four and 14, perhaps a result of weaning or the removal of marine proteins during a period of famine or illness.

Strontium, oxygen, nitrogen and carbon isotope analyses performed on a tooth and rib revealed that the individual grew up in the Northern or Western Isles of Britain, so was probably a local Tiree girl. Her diet was based primarily on terrestrial plants and proteins with very little in the way of marine vegetables and fish. As weird as that seems, it is consistent with other Neolithic remains from farming communities on the western seaboard (and with medieval Viking settlers in Greenland). It seems the island life in the Neolithic era did not involve eating much of the abundant fish and seaweed all around them. The levels of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the layers of dentine in the tooth indicated a major dietary or physiological stress between the ages of four and 14, perhaps a result of weaning or the removal of marine proteins during a period of famine or illness.

Professor Ian Armit, from Bradford University, said: “The earliest case of rickets in Britain until now dated from the Roman period, but this discovery takes it back more than 3,000 years. There have been a few possible cases in other parts of the world that are around the same time, but none as clear cut as this.”

Professor Armit said it was unclear how the woman would have developed rickets.

“Vitamin D deficiency shouldn’t be a problem for anyone exposed to a rural, outdoor lifestyle, so there must have been particular circumstances that restricted this woman’s access to sunlight as a child,” he said.

“It’s most likely she either wore a costume that covered her body or constantly remained indoors, but whether this was because she held a religious role, suffered from illness or was a domestic slave, we will probably never know.”