Five years ago, the Western Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America filed a $105 million lawsuit against the J. Paul Getty Museum alleging that the museum was wrongfully in possession of seven pages ripped out of the 13th century Bible that belongs to the Church. Now the parties have come to an agreement: the Getty acknowledges that the Armenian Apostolic Church owns the pages; the Church donates the pages to the Getty. This way nothing has to actually move or change hands, but the Getty, which in its initial response to the suit insisted that it had “legal ownership” of the pages and that the lawsuit was “groundless and should be dismissed,” has to admit the Armenian Apostolic Church is the true owner.

Five years ago, the Western Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America filed a $105 million lawsuit against the J. Paul Getty Museum alleging that the museum was wrongfully in possession of seven pages ripped out of the 13th century Bible that belongs to the Church. Now the parties have come to an agreement: the Getty acknowledges that the Armenian Apostolic Church owns the pages; the Church donates the pages to the Getty. This way nothing has to actually move or change hands, but the Getty, which in its initial response to the suit insisted that it had “legal ownership” of the pages and that the lawsuit was “groundless and should be dismissed,” has to admit the Armenian Apostolic Church is the true owner.

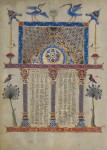

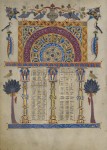

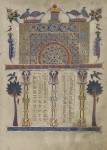

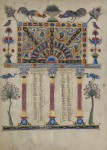

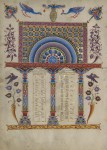

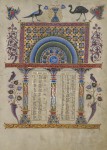

The Zeyt’un Gospels were commissioned in 1256 by the Catholikos, the leader of the Armenian Church, Constantine I. This Bible is the first signed works of T’oros Roslin, scribe and the greatest Armenian illuminator of the Middle Ages. The pages (there are actually eight of them; the Church didn’t know about the last one when it filed) are canon tables, concordances listing passages in the Gospels that describe the same event. The text is therefore sparse, just chapter and verse references.

The Zeyt’un Gospels were commissioned in 1256 by the Catholikos, the leader of the Armenian Church, Constantine I. This Bible is the first signed works of T’oros Roslin, scribe and the greatest Armenian illuminator of the Middle Ages. The pages (there are actually eight of them; the Church didn’t know about the last one when it filed) are canon tables, concordances listing passages in the Gospels that describe the same event. The text is therefore sparse, just chapter and verse references.

In the Middle Ages, canon tables were often depicted in an architectural setting, the columns of numbers placed between drawings of literal columns. What makes these pages exceptional is the illumination by T’oros Roslin who decorated each page in a riot of brilliant colors and gold paint. The tables are divided by columns and topped with intricately detailed geometric panels. Birds, vines, trees, vases line the borders and stand proudly atop the header panels. No two pages are the same.

In the Middle Ages, canon tables were often depicted in an architectural setting, the columns of numbers placed between drawings of literal columns. What makes these pages exceptional is the illumination by T’oros Roslin who decorated each page in a riot of brilliant colors and gold paint. The tables are divided by columns and topped with intricately detailed geometric panels. Birds, vines, trees, vases line the borders and stand proudly atop the header panels. No two pages are the same.

This Bible, in addition to being an irreplaceable Armenian national treasure, is held to be sacred and miraculous. The Zeyt’un Gospels were venerated as having protective powers which is why in 1915 when the Ottoman government began massacring Armenians, the book was carried through every street of Zeyt’un in an attempt to ensure the entire city would be under its divine protection.

Later that year, church officials gave the Bible to a member of the Armenian royal Sourenian family. The Sourenians had connections in the upper echelons of the Ottoman government, so the hope was they wouldn’t be killed or deported and could keep the Gospels safe. They lasted a year before they were deported to Marash in 1916, but they did receive special treatment that allowed them to survive transportation instead of starving to death like so many of their compatriots.

Later that year, church officials gave the Bible to a member of the Armenian royal Sourenian family. The Sourenians had connections in the upper echelons of the Ottoman government, so the hope was they wouldn’t be killed or deported and could keep the Gospels safe. They lasted a year before they were deported to Marash in 1916, but they did receive special treatment that allowed them to survive transportation instead of starving to death like so many of their compatriots.

The Sourenian pater familias loaned the Bible to his friend Dr. H. Der Ghazarian for what was supposed to be a few days. At the perfectly wrong time, the Sourenians were unexpectedly deported and lost track of the Zeyt’un Gospels. It seems the book remained in Marash for the duration of World War I. It surfaced there in 1928 but various obstacles kept it out of the Church’s hands until 1948 when the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul took possession of it and gave it to the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan, Armenia, for safekeeping and display. The Bible remains there to this day.

The Sourenian pater familias loaned the Bible to his friend Dr. H. Der Ghazarian for what was supposed to be a few days. At the perfectly wrong time, the Sourenians were unexpectedly deported and lost track of the Zeyt’un Gospels. It seems the book remained in Marash for the duration of World War I. It surfaced there in 1928 but various obstacles kept it out of the Church’s hands until 1948 when the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul took possession of it and gave it to the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts in Yerevan, Armenia, for safekeeping and display. The Bible remains there to this day.

The missing pages were spotted in 1948 when the Bible returned from Aleppo after it was authenticated by the same Dr. Ghazarian who had it for a while during the war. Although the Church investigated, it was never able to discover who stole the pages and when. At some point the pages ended up in an anonymous private collection in Watertown, Massachusetts. They were seen in public for the first time since the Genocide when the collector loaned the pages to the Morgan Library for a 1994 exhibition. After that exhibition, the Getty acquired the pages. Thirteen years later, Armenian attorney Vartkes Yeghiayan who has often represented victims of the Armenian Genocide

The missing pages were spotted in 1948 when the Bible returned from Aleppo after it was authenticated by the same Dr. Ghazarian who had it for a while during the war. Although the Church investigated, it was never able to discover who stole the pages and when. At some point the pages ended up in an anonymous private collection in Watertown, Massachusetts. They were seen in public for the first time since the Genocide when the collector loaned the pages to the Morgan Library for a 1994 exhibition. After that exhibition, the Getty acquired the pages. Thirteen years later, Armenian attorney Vartkes Yeghiayan who has often represented victims of the Armenian Genocide  discovered the pages were at the Getty and alerted the Church. The Getty refused all requests to repatriate the unquestionably stolen pages and the lawsuit ensued.

discovered the pages were at the Getty and alerted the Church. The Getty refused all requests to repatriate the unquestionably stolen pages and the lawsuit ensued.

It seems to me the Church is conceding a great deal for the sake of a statement of historical ownership. There really is no question that the pages were stolen, so why shouldn’t they be reunited with the rest of the Bible?

The following statement from Getty director Timothy Potts irks me:

“That the pages were saved from destruction and conserved in a museum all these years means that these irreplaceable representations of Armenia’s rich artistic heritage have been and will be preserved for future generations.”

The removal of the pages was the destruction. They weren’t “saved.” They were ripped out and sold on the black market, bought by unscrupulous collectors and the Getty. The Bible itself survived a genocide and two world wars and has been conserved in a museum for 67 years. The Getty having taken care of blatantly stolen pages for a decade hardly makes it the heritage-preserving hero of the piece.

The removal of the pages was the destruction. They weren’t “saved.” They were ripped out and sold on the black market, bought by unscrupulous collectors and the Getty. The Bible itself survived a genocide and two world wars and has been conserved in a museum for 67 years. The Getty having taken care of blatantly stolen pages for a decade hardly makes it the heritage-preserving hero of the piece.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys seem happy, at any rate.

“This is a momentous occasion for the Armenian people, coming at a historic time, on the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. I want to thank the Getty for joining in a solution that recognizes the historical suffering of the Armenian people and that will also allow this Armenian treasure to remain in the museum which has cared for it and made it available to the Armenian and larger community in Los Angeles. We are pleased that both sides arrived at an amicable solution,” said Lee Crawford Boyd, the Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck shareholder representing the Western Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church of America. “The sacred Canon Tables are now being recognized as having belonged to the Armenian Church. Together with the Church and the Armenian people, we are thrilled with this outcome.”

No word on whether this on-paper ownership switcheroo was accompanied by some kind of financial settlement.

No word on whether this on-paper ownership switcheroo was accompanied by some kind of financial settlement.

To learn more about the Armenian Genocide, including primary sources, maps, eye-witness statements, a timeline of events and a collection of horrifying photographs, please visit the website of the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute.