Legend holds that in 366 A.D., a Buddhist monk named Yuezun saw a vision of a thousand Buddhas on the face of a cliff near the town of Dunhuang in the Gobi Desert of northwest China. He began digging caves into the cliff face to make his vision a reality. Who knows if there was a Yuezun who had a vision, but it’s undeniable that in the 4th century, Buddhist monks began to dig grottoes into the cliffs and they didn’t stop for a thousand years.

Legend holds that in 366 A.D., a Buddhist monk named Yuezun saw a vision of a thousand Buddhas on the face of a cliff near the town of Dunhuang in the Gobi Desert of northwest China. He began digging caves into the cliff face to make his vision a reality. Who knows if there was a Yuezun who had a vision, but it’s undeniable that in the 4th century, Buddhist monks began to dig grottoes into the cliffs and they didn’t stop for a thousand years.

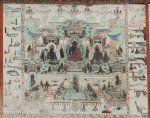

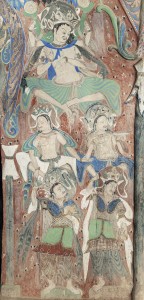

From the 4th to the 14th century, the monks, sponsored by politicians and wealthy donors who wished to express their religious devotion, dug 492 caves and decorated them with exquisite wall paintings, tile work and more than 2,000 clay sculptures of Buddhas, bodhisattvas and other figures. The largest sculpture is a Buddha about 116 feet high, the third largest Buddha sculpture in China, which was made during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.). In total, there are almost 500,000 square feet of painted walls and ceilings depicting Buddhist stories, sutras, donors, abstract ornament and scenes of daily life.

From the 4th to the 14th century, the monks, sponsored by politicians and wealthy donors who wished to express their religious devotion, dug 492 caves and decorated them with exquisite wall paintings, tile work and more than 2,000 clay sculptures of Buddhas, bodhisattvas and other figures. The largest sculpture is a Buddha about 116 feet high, the third largest Buddha sculpture in China, which was made during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 A.D.). In total, there are almost 500,000 square feet of painted walls and ceilings depicting Buddhist stories, sutras, donors, abstract ornament and scenes of daily life.

The enormity of the Mogao Caves (Mogao means “peerless”) complex is a testament not just to the religious dedication of the monks, but to its location along the Silk Road. The evidence of the rich cultural exchange brought to the site by the Silk Road is evident in the mixed influences of the art, and it was the demise of the Road which led to the abandonment of the caves in the 15th century. They were all but forgotten, the painstakingly carved and painted grottoes sealed with sand from the Gobi Desert.

The enormity of the Mogao Caves (Mogao means “peerless”) complex is a testament not just to the religious dedication of the monks, but to its location along the Silk Road. The evidence of the rich cultural exchange brought to the site by the Silk Road is evident in the mixed influences of the art, and it was the demise of the Road which led to the abandonment of the caves in the 15th century. They were all but forgotten, the painstakingly carved and painted grottoes sealed with sand from the Gobi Desert.

Hundreds of years would pass before someone embraced the ancient complex again. A Daoist monk named Wang Yuanlu took it upon himself to care for the caves in around 1892. Entirely alone and unsupported, he began to clean the sand choking the temples and repair the wooden elements. In 1900, he opened a cave that had been sealed in about 1000 A.D. and discovered a massive cache of documents without parallel in human history.

Hundreds of years would pass before someone embraced the ancient complex again. A Daoist monk named Wang Yuanlu took it upon himself to care for the caves in around 1892. Entirely alone and unsupported, he began to clean the sand choking the temples and repair the wooden elements. In 1900, he opened a cave that had been sealed in about 1000 A.D. and discovered a massive cache of documents without parallel in human history.

Cave 17, which for obvious reasons became known as the Library Cave, held almost 50,000 manuscripts, printed texts, paintings on silk and paper, intricate embroidered silks and other textiles. The dry air of the Gobi had preserved them in exceptional condition. The documents provide a unique view of life in medieval China. There are financial ledgers, calendars, legal papers, property sale contracts, dictionaries, medical books, artworks that capture the music, dancing and games of the period. The are Confucian, Daoist and Christian texts are written in Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Hebrew, Tangut, Old Turkish and other languages spoken along the Silk Road.

Cave 17, which for obvious reasons became known as the Library Cave, held almost 50,000 manuscripts, printed texts, paintings on silk and paper, intricate embroidered silks and other textiles. The dry air of the Gobi had preserved them in exceptional condition. The documents provide a unique view of life in medieval China. There are financial ledgers, calendars, legal papers, property sale contracts, dictionaries, medical books, artworks that capture the music, dancing and games of the period. The are Confucian, Daoist and Christian texts are written in Chinese, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Hebrew, Tangut, Old Turkish and other languages spoken along the Silk Road.

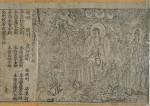

The stand-out document amidst the vast archival treasure discovered in the cave is the Diamond Sutra, the world’s earliest printed dated book. A copy of an ancient Indian Buddhist text, this Chinese translation of the Diamond Sutra was made in 868 A.D., and we know this because the maker noted it in the colophon: “Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents, 11 May 868.” While there are extant woodblock printed art works on silk from the 3rd century, the earliest fragments of printing on paper date to the mid-7th century. Woodblock printing was established by the 8th century, but the Diamond Sutra is the first complete book that we have a precise date for known to survive. It is a scroll more than 15 feet long made from seven panels of paper pasted together.

The stand-out document amidst the vast archival treasure discovered in the cave is the Diamond Sutra, the world’s earliest printed dated book. A copy of an ancient Indian Buddhist text, this Chinese translation of the Diamond Sutra was made in 868 A.D., and we know this because the maker noted it in the colophon: “Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents, 11 May 868.” While there are extant woodblock printed art works on silk from the 3rd century, the earliest fragments of printing on paper date to the mid-7th century. Woodblock printing was established by the 8th century, but the Diamond Sutra is the first complete book that we have a precise date for known to survive. It is a scroll more than 15 feet long made from seven panels of paper pasted together.

Keen to preserve this great collection, Wang showed some of the texts to local government officials but they showed zero interest. In 1904, the governor order the Library Cave be resealed. Word of the find got out to archaeologists and explorers and in 1907 British archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein offered to buy thousands of the manuscripts and artworks. This is Stein’s description of Cave 17:

Keen to preserve this great collection, Wang showed some of the texts to local government officials but they showed zero interest. In 1904, the governor order the Library Cave be resealed. Word of the find got out to archaeologists and explorers and in 1907 British archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein offered to buy thousands of the manuscripts and artworks. This is Stein’s description of Cave 17:

“The sight of the small room disclosed was one to make my eyes open wide. Heaped up in layers, but without perfect order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest’s little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet, and filling, as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet. The area left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to stand in.”

Wang wanted to build a Daoist temple but he had no money and since the government had told him to shove it in regards to conserving the Library Cave’s library, he went ahead and sold the documents to Stein for a pittance. The next year explorer French Paul Pelliot bought more than 10,000 pieces from Cave 17. Then came the Germans, Russians and Japanese. The collection was thoroughly picked over by the time the sales stopped with the beginning of World War I. Finally resurgent nationalism in the 1920s woke the Chinese government up and the remaining documents were moved to the National Library of China in Beijing.

Wang wanted to build a Daoist temple but he had no money and since the government had told him to shove it in regards to conserving the Library Cave’s library, he went ahead and sold the documents to Stein for a pittance. The next year explorer French Paul Pelliot bought more than 10,000 pieces from Cave 17. Then came the Germans, Russians and Japanese. The collection was thoroughly picked over by the time the sales stopped with the beginning of World War I. Finally resurgent nationalism in the 1920s woke the Chinese government up and the remaining documents were moved to the National Library of China in Beijing.

The Diamond Sutra was acquired in 1907 by Stein and is now in the British Library along with more than 400 other pieces from Dunhuang. (The BL, incidentally, has spearheaded the International Dunhuang Project, an initiative to digitize images of texts, art and textiles found at Dunhuang and other archaeological sites of the Eastern Silk Road. There are almost a million images in the database as of now, and they’re not done yet.)

The Diamond Sutra was acquired in 1907 by Stein and is now in the British Library along with more than 400 other pieces from Dunhuang. (The BL, incidentally, has spearheaded the International Dunhuang Project, an initiative to digitize images of texts, art and textiles found at Dunhuang and other archaeological sites of the Eastern Silk Road. There are almost a million images in the database as of now, and they’re not done yet.)

The Diamond Sutra hasn’t left Britain in more than a century, but that’s about to change. It will be the star of the Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road exhibition at the Getty Center in Los Angeles. The Getty Conservation Institute has been working closing with the Dunhuang Academy since 1989 to conserve the paintings on the walls of the Mogao Grottoes. To give visitors a

The Diamond Sutra hasn’t left Britain in more than a century, but that’s about to change. It will be the star of the Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road exhibition at the Getty Center in Los Angeles. The Getty Conservation Institute has been working closing with the Dunhuang Academy since 1989 to conserve the paintings on the walls of the Mogao Grottoes. To give visitors a  truly immersive experience, the Getty has constructed exact replicas of three of the caves. These aren’t Hollywood sets made to look like the grottoes. The replicas are precise duplicates in shape, size and decoration. The replica paintings were done using the same pigments originally used in Dunhuang. The Getty even imported the actual clay used to sculpt the Buddhas and bodhisattvas that inhabit the caves.

truly immersive experience, the Getty has constructed exact replicas of three of the caves. These aren’t Hollywood sets made to look like the grottoes. The replicas are precise duplicates in shape, size and decoration. The replica paintings were done using the same pigments originally used in Dunhuang. The Getty even imported the actual clay used to sculpt the Buddhas and bodhisattvas that inhabit the caves.

The exhibition runs from May 7th through September 4th, 2016. For those four months, Los Angeles may be the closest you can get to the Gobi Desert and the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/Owy3GhtXAvY&w=430]