Archaeologists excavating the Acemhöyük excavation site in central Turkey have unearthed a clay rattle that dates to the early Bronze Age. It has not been radiocarbon dated yet, but the layer in which it was found dates to around 2200 B.C. which makes the toy one of the oldest rattles ever found. Made out of terracotta, the rattle is shaped like an oval coin purse. It probably had a handle originally but that has been lost. The top has a few perforations to allow sound to escape. It is intact and still sealed with small objects inside, probably pebbles, which make the rattling noise. Had any part of it broken or chipped over the past 4,000 years, the contents would have fallen out and it would no longer rattle. Happenstance has preserved it so that we can still hear what the Bronze Age baby and parents who once shook it can hear.

Archaeologists excavating the Acemhöyük excavation site in central Turkey have unearthed a clay rattle that dates to the early Bronze Age. It has not been radiocarbon dated yet, but the layer in which it was found dates to around 2200 B.C. which makes the toy one of the oldest rattles ever found. Made out of terracotta, the rattle is shaped like an oval coin purse. It probably had a handle originally but that has been lost. The top has a few perforations to allow sound to escape. It is intact and still sealed with small objects inside, probably pebbles, which make the rattling noise. Had any part of it broken or chipped over the past 4,000 years, the contents would have fallen out and it would no longer rattle. Happenstance has preserved it so that we can still hear what the Bronze Age baby and parents who once shook it can hear.

You can see and hear the rattle rattled in this Turkish language news story on the find.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/DdCvsyLkCcg&w=430]

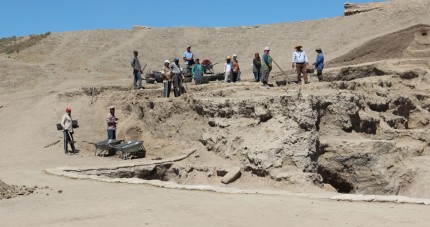

That’s Dr. Aliye Öztan in the video, leader of the excavations at Acemhöyük since 1989. Acemhöyük is a large oval mound 44 hectares in area that is one of the largest Bronze Age sites in Anatolia. The tumulus was erected around 3000 B.C. There are a total of 12 habitation layers, the oldest dating to the Late Copper Age. The rattle was found in layer seven. The settlement was continually inhabited from the Early Bronze Age through the Roman era, reaching peak prosperity in the second millennium B.C. when it was an important center of trade during the Assyrian Trade Colonies Period (1950-1750 B.C.) when the Assyrians established karums, or merchant colonies, in multiple cities in Anatolia.

Excavations at the site began in 1962 and have continued ever since. While earlier excavations have focused on the prosperous Assyrian Trade Colonies Period, the aims of the current dig is to excavate the bottom layer of the mound and the Early Bronze Age ones. The city walls were built in the Early Bronze Age, so this period is key to understanding the community’s growth and development. Other artifacts found this season include a fragment of a necklace made of bones, metal needles and cups.