Two oil paintings stolen from the Van Gogh Museum in 2002 were found by Italian police in a town outside of Naples. The anti-mafia squad raided the apartment of Raffaele Imperiale, a major drug dealer who is currently on the lam probably in the United Arab Emirates, in the village of Castellammare di Stabia as part of a large-scale investigation into drug smuggling by the Amato Pagano clan affiliated with the Camorra, the mafia-like criminal organization centered in Naples. It was in the basement that they found the two paintings wrapped in cloth.

Two oil paintings stolen from the Van Gogh Museum in 2002 were found by Italian police in a town outside of Naples. The anti-mafia squad raided the apartment of Raffaele Imperiale, a major drug dealer who is currently on the lam probably in the United Arab Emirates, in the village of Castellammare di Stabia as part of a large-scale investigation into drug smuggling by the Amato Pagano clan affiliated with the Camorra, the mafia-like criminal organization centered in Naples. It was in the basement that they found the two paintings wrapped in cloth.

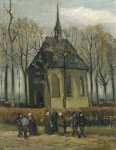

The police called in experts to confirm the identity of the paintings, but they already knew what they had. The theft from Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum is notorious, one of the FBI’s top 10 art crimes thanks to the paintings’ (very conservative) estimated value of $30 million. The two thieves climbed a ladder to the roof and broke into the museum in December of 2002. They stole Seascape at Scheveningen (1882) and Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen (1884/85), two of the artist’s important early works. Two men were convicted of the theft a year later, but the paintings were never recovered and how they wound up a thousand miles south of Amsterdam in the hands of Camorristi 14 years later remains a mystery.

Van Gogh Museum officials are ecstatic. Museum director Axel Rüger said at the press conference in Naples: “The paintings have been found! That I would be able to ever pronounce these words is something I had no longer dared to hope for.” The paintings are priceless to the museum, of course; their less left the collection with yawning lacunae.

The art historical value of the paintings for the collection is huge. Seascape at Scheveningen is the only painting in our museum collection dating from Van Gogh’s period in The Hague (1881-1883). It is one of the only two seascapes that he painted during his years in the Netherlands and it is a striking example of Van Gogh’s early style of painting, already showing his highly individual character. The hoped-for forthcoming return of the Seascape will fill an important gap in the museum presentation.

Congregation leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen is a small canvas that Van Gogh painted for his mother in early 1884. It shows the church of the Reformed Church community in the Brabant village of Nuenen, Van Gogh’s father being its Minister. In 1885, after his father’s death, Van Gogh reworked the painting and added the churchgoers in the foreground, among them a few women in shawls worn in times of mourning. This may be a reference to his father’s death. The strong biographical undertones make this a work of great emotional value. The museum collection does not include any other painting depicting the church. Moreover, it is the only painting in the Van Gogh Museum collection still in its original stretcher frame. This frame is covered in splashes of paint because Van Gogh probably cleaned his brushes on it.

Colonel Giovanni Salerno, head of the Guardia di Finanzia (financial police) division that executed the raid, said they recognized those unique paint marks on the back even before the paintings were authenticated as the missing Van Goghs.

Colonel Giovanni Salerno, head of the Guardia di Finanzia (financial police) division that executed the raid, said they recognized those unique paint marks on the back even before the paintings were authenticated as the missing Van Goghs.

The works appear to be in good condition, all things considered. The frames are gone. Seascape at Scheveningen has suffered some damage and is missing a small rectangle of paint (5 x 2 cm) from the bottom left corner. Congregation leaving the Reformed Church in Nuenen has some damage around the edges. Conservators will have to examine them more closely to assess their condition. Clearly they have not been kept in ideal climactic condition, so there’s bound to be issues there.

Because the paintings are evidence in a giant organized crime case, they won’t be heading back to Amsterdam anytime soon. They will remain in the hands of Italian law enforcement at least until the criminal case is presented in court, perhaps even through the trial, which could take years. Police in Italy are very sensitive to art theft issues, however, and the museum has every confidence that they’ll do their utmost to get the paintings home as soon as possible.